OSS 117: Lost in Rio

By Brian Eggert |

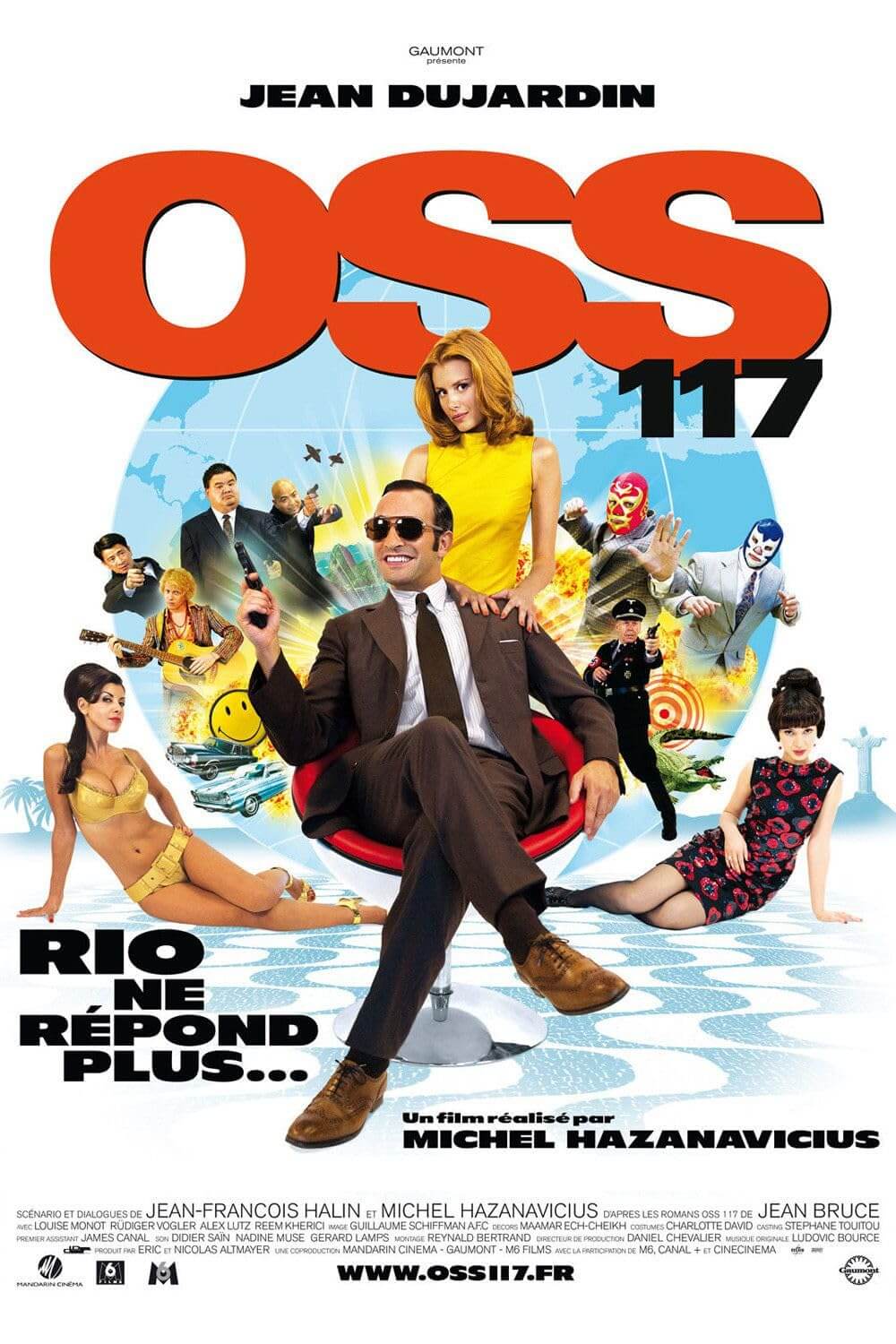

His name is Hubert Bonisseur de La Bath. Codename: OSS 117. As France’s top superspy, he’s known the world over as a liberator of countries and conqueror of countless women. No one can kill him, nor make him commit to a single woman. His skills in combat and in the bedroom are many. He is also a self-absorbed idiot, an out-of-date racist, and misogynist, and his reputation proves exaggerated to anyone who meets him. He’s played by comedian Jean Dujardin in OSS 117: Lost in Rio, who reprises his role here in the sequel to 2006’s original, leading an impressive production that parodies 1960s-era spy stories to hilarious effect.

For readers not up to snuff on their spy yarn history, Frenchman Jean Bruce created OSS 117 back in 1949, four years prior to Ian Fleming publishing his first James Bond novel, whereas the first OSS 117 film came ten years before the first Bond film. Both are suave superspies engaged in womanizing and impossible heroics, and both are products of their time. Director Michel Hazanavicius clearly identifies with the Fleming ideal standardized in more than thirty Hollywood Bond films, whereas Bruce’s character has had only a handful of filmic adaptations, none of them in English—the best of them being Hazanavicius’ first entry into the spoof series, OSS 117: Cairo, Nest of Spies.

The film opens in 1967, twelve years after the events in the previous entry. The hilariously stupid de la Bath accepts a mission where he must fly to Rio de Janeiro and deliver a ransom demanded by a Nazi war criminal (Rüdiger Vogler) for a microfilm containing a list of French collaborators from World War II. (Notice the mission isn’t to catch the war criminal, rather just to pay him off.) While there, he plans to catch some sun and enjoy Brazilian women, but those plans are thwarted when he’s teamed with feminist Mossad agent Dolores (Louise Monot), whose “make love, not war” principles hardly mesh with de la Bath’s sexism and propensity for violence. While trying to make contact with the Nazi spy, de la Bath faces rejection from Dolores, an onslaught of English-language insults from his CIA contact, which he does understand, and a homosexual encounter on a hippie beach.

Much of the humor in the film falls into the realm of de la Bath’s ironic stereotyping, his racial ignorance and male elitism, and his unfashionable behavior in a swingin’ city like Rio. In an early scene, he attempts to convince members of the Mossad about the truths of Jewish money hoarding. Then, forgetting he’s in the liberated ‘60s, the character preaches to flower children that “reality will arrive in the form of a haircut.” Later he slaps a German hippie for not following his father, though his father was a Nazi— apparently breaking the traditionalism of family hierarchy is more offensive than fascism. Through it all, Dujardin, who recalls a combination of Jerry Lewis and Sean Connery, plays the role as straight as can be. He’s silly, of course, but the actor isn’t winking at the camera like Mike Myers in the Austin Powers movies, which is a relief.

Hazanavicius makes his comedy more than just a spoof through his faultless ‘60s mise-en-scéne—a film theory term that, if you’re unfamiliar with it, begs the question: Why are you reading a review for a subtitled French comedy? This element made this film’s predecessor stand out as well, and it’s what separates the series from comparable, popular dribble such as the Austin Powers franchise. Hazanavicius uses color saturations, impeccable costume/makeup/set design, and grainy cinematography to capture the look and feel of a ‘60s spy yarn. If it weren’t for the humor filled with historical ironies, you might be fooled into believing the film was actually made in the period that it lampoons.

More than just the visual approach resembling early Bond movies, however, Hazanavicius pays homage to several Alfred Hitchcock films, resulting in a curious blend of Bond-meets-Hitchcock that strangely works here. Consider these hints: The scenario involves de la Bath hunting for Nazi spies in Rio, much like the debonair Cary Grant in Notorious. De la Bath has a staggering fear of heights resulting from an earlier tragedy, and he’s forced to confront that fear in the finale, just as James Stewart does in Vertigo. Ludovic Bource’s score mimics the one by Bernard Herrmann for North by Northwest, which is also paralleled in the climactic chase atop Rio’s statue of Christ the Redeemer—although, Hitchcock ended several pictures atop monuments, such as The Statue of Liberty in Saboteur. These references show that Hazanavicius is more interested in embracing film history than pop culture, which makes his spoof all the more enjoyable, even artful, next to trash like Hollywood’s Vampires Suck or Scary Movie.

Music Box has imported the French film, reducing it to a limited release no doubt because of English subtitles, and because American audiences aren’t much for readin’ while watchin’. Although, one can’t help but wonder how well the comedy would do if given wide distribution. Probably very well. Certainly, general audiences could identify much of the racial humor, as well as the French production’s willingness to poke fun at its own nationality (Americans have always enjoyed laughing at the French). Maybe for the third film in the inevitable trilogy, the efforts of Dujardin and Hazanavicius will be recognized by a greater U.S. audience thanks to good word of mouth; otherwise, only arthouse attendees and those seeking foreign gems on DVD will discover it.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review