Nouvelle Vague

By Brian Eggert |

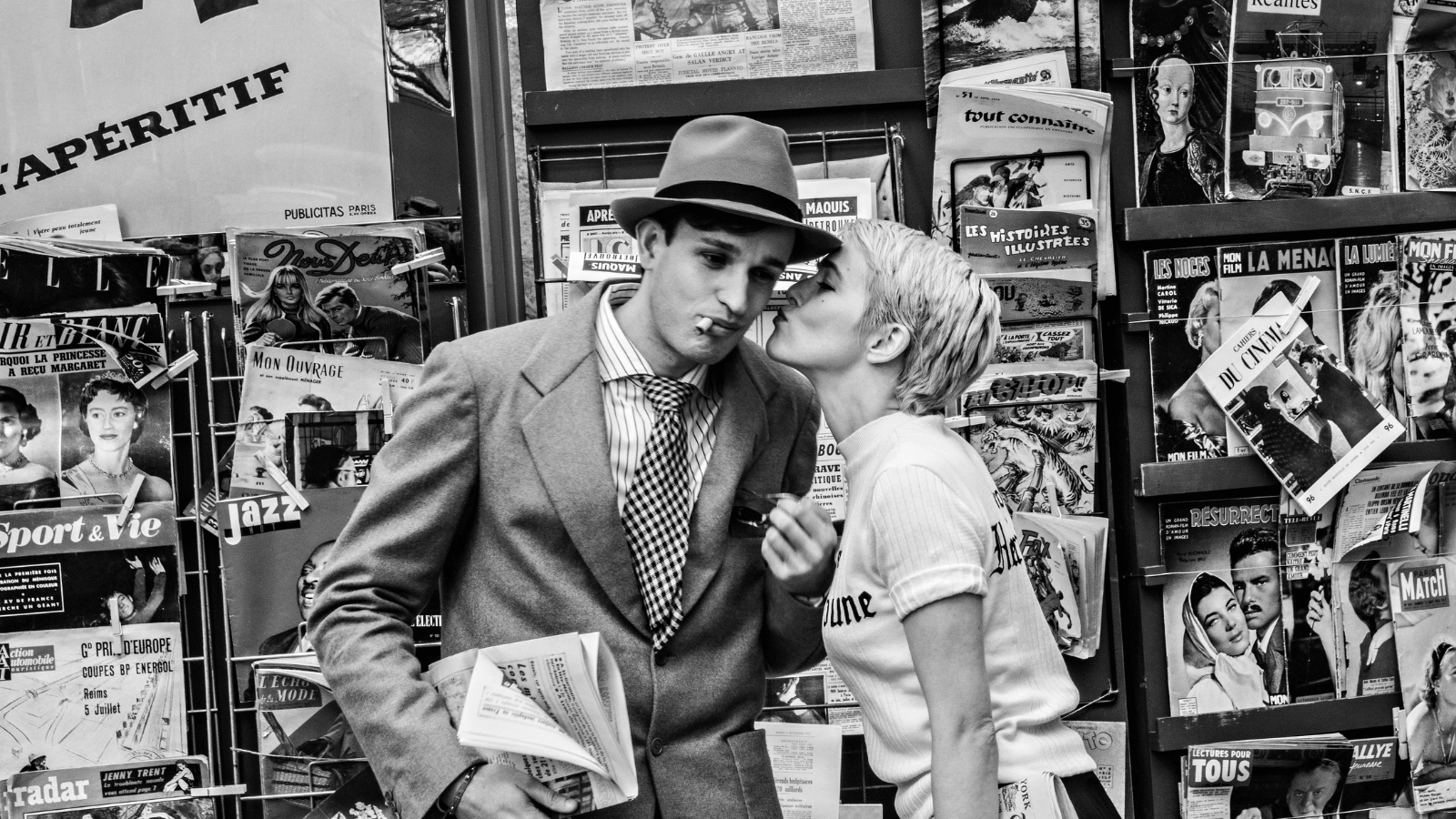

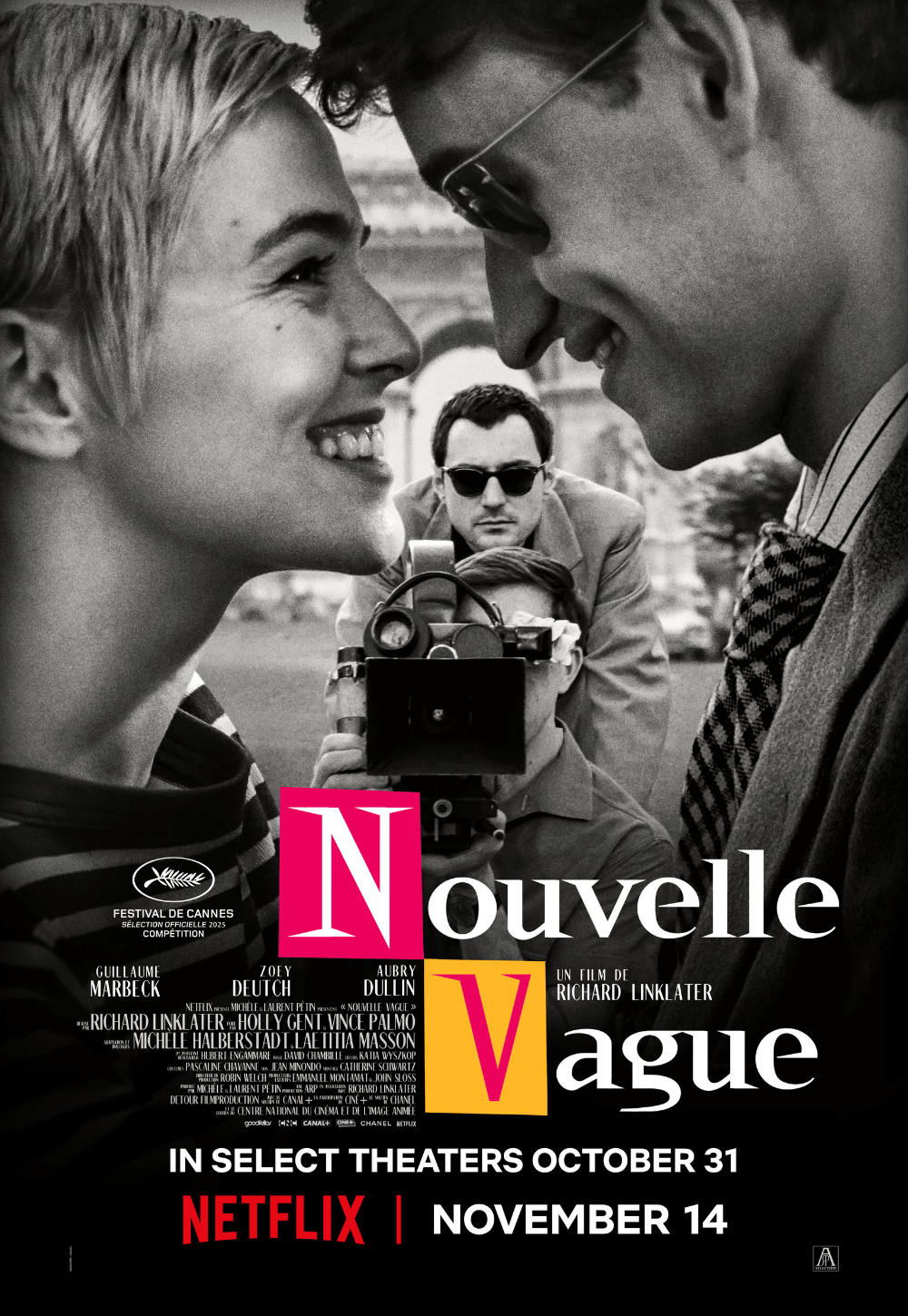

In my experience—and I’m making a broad generalization here based on anecdotal evidence—cinephiles respond to Jean-Luc Godard in one of two ways: they either think he’s an incomparable genius of European arthouse cinema, or they find him to be overly self-conscious and obnoxiously Brechtian, his work too much about aesthetic posturing and difficult to connect with on an emotional level. I fall in the latter camp, though I recognize Godard’s innovations in the form that influenced filmmakers such as Arthur Penn, Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino, Wong Kar-wai, and Steven Soderbergh, to name a few. Godard’s directorial debut, Breathless (1960), remains his most famous feature and helped define the French New Wave. Richard Linklater’s Nouvelle Vague is about the making of Godard’s avant-garde film, and he crafted it in the style of its namesake, complete with black-and-white photography, abrupt cutting, and many other visual trademarks of the era. And while the focus remains on Godard’s production, Linklater’s film doubles as an inspired demonstration of New Wave aesthetic philosophy.

The New Wave launched in the late 1950s, spearheaded by critics from the Cahiers du cinéma. The movement was a reaction to the “Tradition of Quality” in the French film industry that valued artifice over substance. Godard, here played by Guillaume Marbeck, and his contemporaries celebrated filmmakers who leave a personal imprint on their work. In short, they value auteurs (the French word for author) who imbue their films with consistent themes and stylistic trademarks, and they championed the artistic legitimacy of Alfred Hitchcock, Nicholas Ray, and Howard Hawks long before their American counterparts did. Many of the Cahiers critics went on to direct features themselves, adopting a stripped-down style that drew inspiration from Italian Neorealism, characterized by the use of actual locations, minimal production values, and untrained actors. The French took the style further by experimenting with nonlinear narratives and discordant editing techniques, which are still seen in movies today.

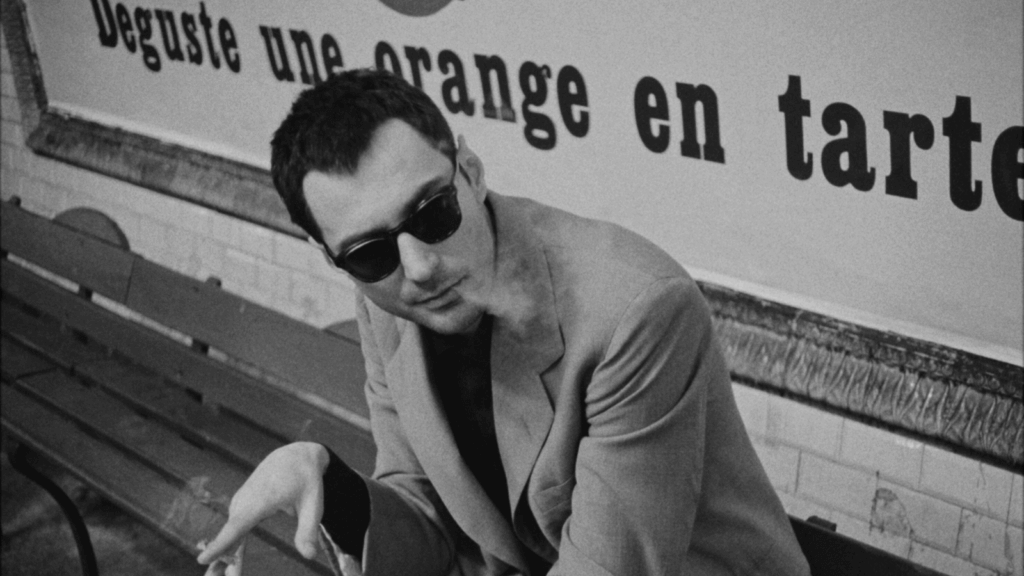

Vincent Palmo Jr. and Holly Gent’s screenplay opens in 1959, after Godard’s fellow critics have already made their first films, among them Claude Chabrol (Antoine Besson), Jacques Rivette (Jonas Marmy), and Eric Rohmer (Côme Thieulin). François Truffaut (Adrien Rouyard) became the most famous of them with The 400 Blows (1959), a film that manages both a moving narrative and a stylistic revolution. Even so, Godard is considered the “real genius” of the bunch for his curt, absolutist aesthetic beliefs. His persistent artistic defiance, marked by his ever-present sunglasses and reputation as an enfant terrible, ensures that his first feature will be unlike anything else—and motivated by some of his most famous real-life quotes, such as “real art avoids artistic effects” and “all you need for a movie is a girl and a gun.” With his film greenlit only because Truffaut and Chabrol agree to have their names loosely attached, Godard receives backing from Georges de Beauregard (Bruno Dreyfürst), a fraught producer who clashes with the director over his erratic shooting schedule and disregard for pesky details like continuity.

Unlike most productions, Godard’s doesn’t begin with a script; instead, he writes a rough outline and resolves to post-sync the dialogue. He wants to “search” for his story and shots. Given the rising popularity of the Cahiers critics’ films, Godard manages to land Hollywood star Jean Seberg (Zoey Deutch), fresh off her two early collaborations with autocrat director Otto Preminger, Saint Joan (1957) and Bonjour Tristesse (1958). He also convinces amateur boxer Jean-Paul Belmondo (Aubry Dullin, a dead ringer for the iconic actor) to play the lead, Michel Poiccard, a petty crook who imagines himself as Humphrey Bogart. Seberg plays Patricia, an American in Paris who rightly suspects Michel killed a cop and ultimately turns him in. Godard enlists wartime cameraman Raoul Coutard (Matthieu Penchinat) to shoot the picture, stealing shots in Paris without a permit by concealing the camera inside a postal cart or in a window.

Throughout the shoot, the cast and crew wait around for Godard to find inspiration, and he often shoots nothing at all, much to de Beauregard’s frustration. When he does, he pontificates as though he’s been making movies for decades, fuelled by his critical tenets. He refuses to allow any pretenses of filmmaking. No makeup on Seberg. No unnatural lighting. No more than one or two takes at most, to preserve the naturalism of the scene. Part of the joy in watching Nouvelle Vague is how Linklater replicates those imperatives in his production, with a jazzy score that nods to the spontaneous structure of Breathless and Godard’s approach to directing. Cinematographer David Chambille shoots with noticeable grain in the Academy aspect ratio of 1.37:1, employing some of the tactics Godard uses onscreen: handheld cameras, characters looking into the lens, and a wheelchair when there’s no money for a dolly. All the while, Godard makes declarations, often quoting philosophers and poets whose axioms have formed his artistic doctrine.

It’s funny how watching a film about the making of Breathless is a more compelling experience than actually sitting down to watch Godard’s film. I’ve never bought into the characters or wannabe mystique of the whole thing; they’ve always seemed slight and hollow, driven by Godard’s artistic ambitions more than relatable behaviors. And based on what we see behind the scenes, Godard didn’t imbue his story with much substance. It’s more about making a statement about art through his alternative approach. Perhaps that’s why I’ve always preferred filmmakers who Godard influenced over his own work. Nevertheless, Linklater’s formal mimicry remains convincing throughout, and his cast is exceptional, with Marbeck and others disappearing into their roles. Deutch is particularly good, capturing Seberg’s stilted delivery of French dialogue and generally uncertain look throughout.

Rather than a biographical portrait of Godard’s life, Linklater’s film celebrates the self-mythologizing Godard and the artistic purity that emerged out of France at this time. It’s staggering to be reminded of how many landmark filmmakers were working in France in the late 1950s besides the Cahiers du cinéma staff, including Jean Cocteau, Robert Bresson, and Jean-Pierre Melville. Doubtless, those with a greater affinity for Breathless than I may enjoy Nouvelle Vague more, but it’s sure to reveal to viewers how impactful the New Wave was on modern cinema, Linklater’s included. Much like Godard, Linklater is an experimenter, challenging formal standards with unconventional methods, whether he’s shooting a trilogy over two decades, a single film over 12 years, or using rotoscoped animation to create an incomparable visual experience. Linklater reminds us that great art takes risks, which is something many filmmakers today have forgotten.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review