Mad Max

By Brian Eggert |

George Miller’s Mad Max takes place at the cusp of oblivion. It’s too soon to call the setting a post-apocalyptic wasteland. Although, it’s getting close. Civilization retains some semblance of its former self, and all humanity has not yet been lost. After an unexplained energy crisis, signs of major societal descent reach the Outback first, and more populated areas such as cities will surely follow. Crime and lawlessness run rampant, and Australia’s government responds by initiating the Main Force Patrol (MFP), a band of heavy-gunner cops in souped-up Interceptor cars. Created to support local authorities and take down an insurgency of marauding gangs, MFP officers have a high mortality rate, save for the fresh-faced title character, played by a young Mel Gibson in his second role. He’s a man alone, an avenging equalizer pitted against a sadistic band of punks. Max seems to represent the last human domino that needs to fall before the apocalypse takes over completely. And by the end, though he will have killed off everyone whom the film’s grim morality deems deserving, he will have lost everything he holds dear in the process.

Mad Max arrived in 1979 after nearly two decades of post-apocalyptic fare had saturated the B-movie market thanks to Roger Corman and countless others like him. In what feels like The Omega Man (1971) by way of Death Race 2000 (1975), the film’s well-treaded scenario wasn’t original at the time and, by no fault of its own, remains almost insultingly basic today. But the undeniably affecting story written by Miller and co-scripter James McCausland delivers more than just blood and guts and automobiles. There are also strong performances, an engaging human drama, and a social commentary to consider, which raises Mad Max above its B-movie contemporaries. Miller and McCausland integrate a sharp if recessive commentary by reflecting on the social consequences of Australia’s then-recent oil crisis. After the outbreak of the 1973 October War, which had not directly involved Australia, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) placed an embargo on all oil exports, resulting in near quadrupled prices on the limited barrels of oil throughout the globe. Miller and McCausland both watched humanity degrade into animal violence as motorists combated for access to gas pumps. Especially in the secluded Outback, where towns were sparse and spread apart by miles of road. Where mobility meant life. These themes are not expressly discussed in the film, and the theme is altogether lost on U.S. audiences, but Australians at the time got the message. Still, a stark commentary about the lowest depths of humanity would not likely draw audiences, nor likely recover their shoestring budget of about $400,000 from independent Australian investors. Instead, the commentary resides under the surface of Miller’s kinetic direction, the high-velocity stunts, and the undeniable charisma of Gibson.

Before becoming a director, Miller attended medical school at the University of New South Wales and served as a doctor in Sydney. There, he witnessed the results of Australia’s obsessive automobile culture that used abandoned roads like racetracks, often resulting in the viscera that later helped inspire the carnage in Mad Max. He had long been interested in filmmaking, and experimented with the medium during his off-hours. Alongside fellow film enthusiast Byron Kennedy, he soon developed a production company called Kennedy Miller, and together they made a popular 20-minute short called Violence in the Cinema, Part 1 (1971). He and Kennedy loved the “pure kinetics of chase movies” like Bullitt (1968), Stone (1974), and Corman’s The Wild One (1954). They also admired post-apocalyptic fare such as A Boy and His Dog (1975). And they explored their enthusiasms when they hired McCausland to co-author Mad Max. Together, they achieved a fast-moving exploitation film that broke box-office records for independent cinema.

Before becoming a director, Miller attended medical school at the University of New South Wales and served as a doctor in Sydney. There, he witnessed the results of Australia’s obsessive automobile culture that used abandoned roads like racetracks, often resulting in the viscera that later helped inspire the carnage in Mad Max. He had long been interested in filmmaking, and experimented with the medium during his off-hours. Alongside fellow film enthusiast Byron Kennedy, he soon developed a production company called Kennedy Miller, and together they made a popular 20-minute short called Violence in the Cinema, Part 1 (1971). He and Kennedy loved the “pure kinetics of chase movies” like Bullitt (1968), Stone (1974), and Corman’s The Wild One (1954). They also admired post-apocalyptic fare such as A Boy and His Dog (1975). And they explored their enthusiasms when they hired McCausland to co-author Mad Max. Together, they achieved a fast-moving exploitation film that broke box-office records for independent cinema.

Mad Max earned $5.3 million in Australia and, after its worldwide distribution, brought its earnings to nearly $100 million. It set long-held records for the most profitable independent film ever produced (a record broken by The Blair Witch Project in 1999). The film was purchased for U.S. distribution by American International Pictures (AIP), which was sold to Filmways, Inc. in 1979, and then renamed Filmways Pictures. During the transition, the distributors treated Mad Max like a foreign-language film and redubbed the Australian dialogue with American accents, giving the picture the sound and look of a Spaghetti Western. Even Gibson’s voice was dubbed, since he was not yet an international star. Regardless, critics recognized Miller’s visual talent and Gibson’s charisma, even while comparing the film to Death Wish (1974) and issuing censures over its unrelenting revenge-based plotting.

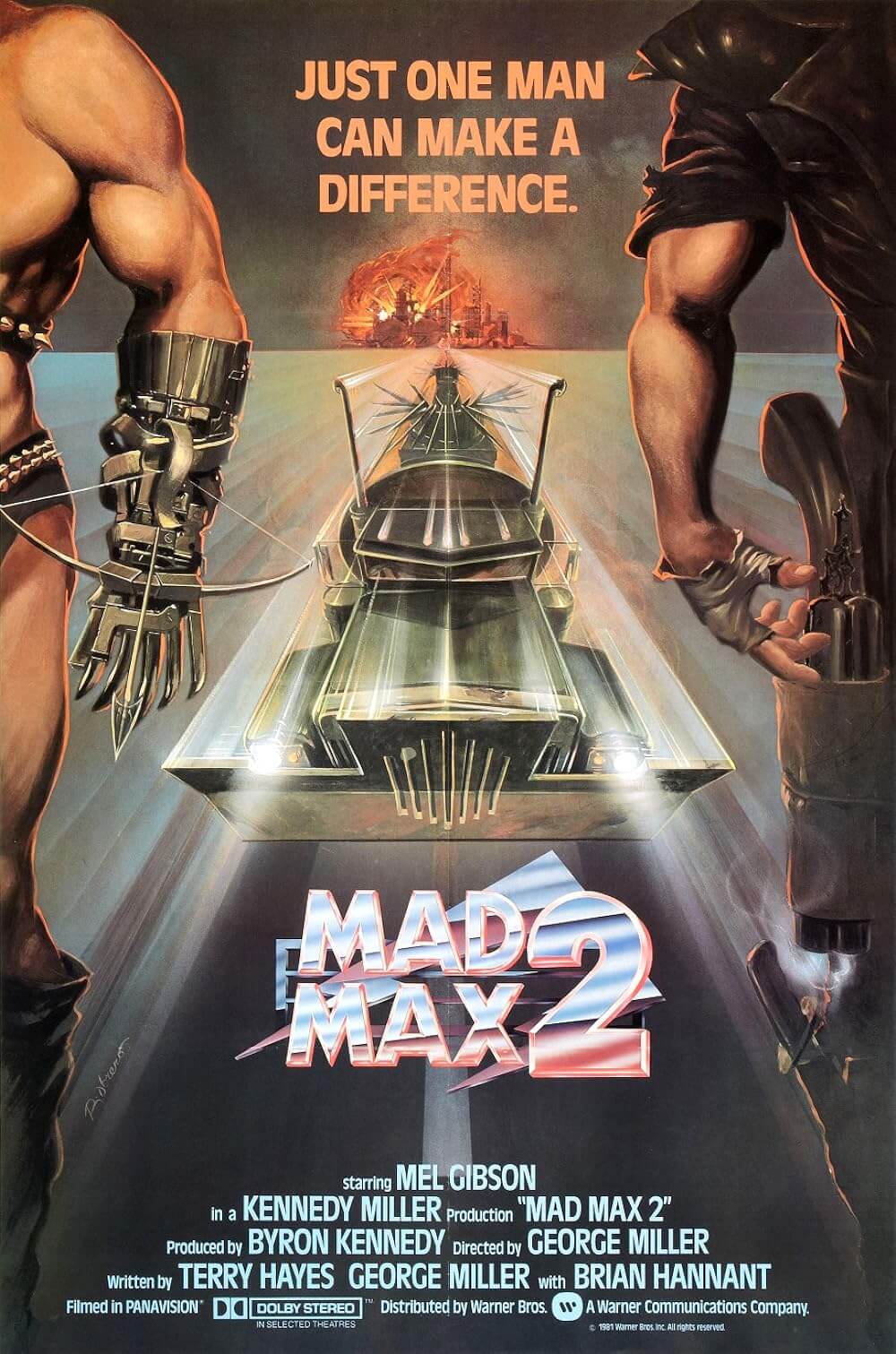

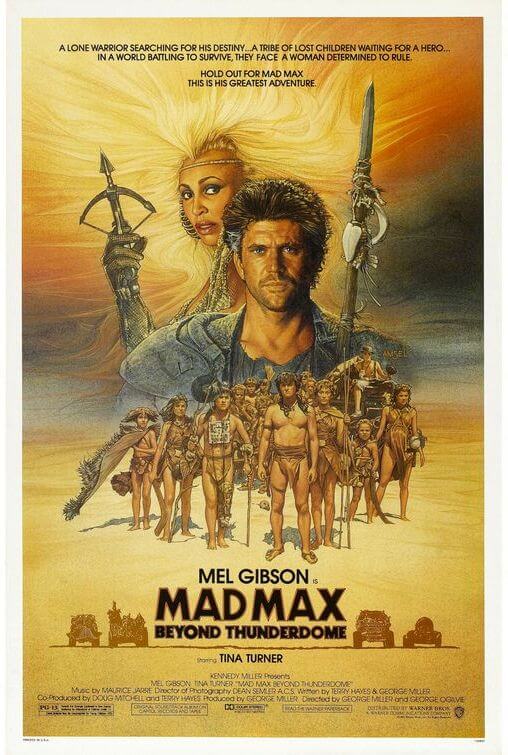

Having appeared in a few dismissible roles, Gibson—the New York-born, Austrailia-raised novice actor—was hired by Miller because the director wanted unknowns. Within a few short years, the actor’s popularity skyrocketed, not only from Mad Max and his next major role in the sequel, Mad Max 2 (1981), but also from Peter Weir’s Gallipoli (1981) and The Year of Living Dangerously (1982). After two Hollywood blockbusters in the late 1980s—Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985) and Lethal Weapon (1987)—Gibson was a household name, a superstar. And yet, he’s a convincing and sympathetic everyman in Miller’s first film. Without these qualities, Max Rockatansky’s dramatic arc would have felt unconvincing and hollow, as would the entire film. Instead, we watch Gibson’s character decompress in warm scenes with his wife (Joanne Samuel) and child, and because Miller allows us these intimate moments, he creates a bond between Max and the audience. Whereas Miller’s later sequels play like nonstop actioners populated by anti-heroic movie tropes, Mad Max offers a fully rounded characterization.

Having appeared in a few dismissible roles, Gibson—the New York-born, Austrailia-raised novice actor—was hired by Miller because the director wanted unknowns. Within a few short years, the actor’s popularity skyrocketed, not only from Mad Max and his next major role in the sequel, Mad Max 2 (1981), but also from Peter Weir’s Gallipoli (1981) and The Year of Living Dangerously (1982). After two Hollywood blockbusters in the late 1980s—Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985) and Lethal Weapon (1987)—Gibson was a household name, a superstar. And yet, he’s a convincing and sympathetic everyman in Miller’s first film. Without these qualities, Max Rockatansky’s dramatic arc would have felt unconvincing and hollow, as would the entire film. Instead, we watch Gibson’s character decompress in warm scenes with his wife (Joanne Samuel) and child, and because Miller allows us these intimate moments, he creates a bond between Max and the audience. Whereas Miller’s later sequels play like nonstop actioners populated by anti-heroic movie tropes, Mad Max offers a fully rounded characterization.

As suggested, the story is straightforward. It follows Max and his partner Goose (Steve Bisley) as they attempt to tame the wild roads of the Outback, while the courts remain ineffectual at maintaining order and the townspeople remain afraid to intervene out of, say, human decency. But people have good reason to be afraid: a gang led by Toecutter (Hugh Keays-Byrne) steals, rapes, and murders at will. Indeed, after gang member Johnny “the Boy” Boyle (Tim Burns) is arrested by Goose and later released for unjust reasons, the gang sabotages Goose’s motorcycle and then burns him alive. Devastated all through the film’s meandering, rather slow second act, Max considers retiring from his chaotic job. He takes a vacation with his family to think it over, and despite removing himself from the insanity of the MFP, danger follows. Toecutter’s gang spots Max’s wife and child, follows them to a secluded farm, and runs them down on the road. With nothing left to live for and propelled by rage, Max hunts down and mercilessly kills Toecutter and his entire gang.

Bleak, fatalistic, and ultimately of questionable morals though this revenge story may be, Miller oversees an incredible technical showcase of inventive camera angles and fast-paced editing. The many car chases throughout the film require precise cross-cutting between the pursuer and pursued to create tension, and editors Tony Paterson and Cliff Hayes know the exact moments to cut away or linger to tie the audience in knots. The film’s high-velocity chases also require daredevil camera placement mounted on the cars themselves; the low, close-to-the-road angles are captured at top speeds by cinematographer David Eggby. The vehicular crashes are visceral and treat automobiles like paper, such as the sequence where an Interceptor bursts through a mobile home during a chase. More punishing is the care with which Miller depicts human violence. Gunshots, beatings, and rape all have an uncomfortable quality that aligns Mad Max with its B-movie roots, largely inspired by Miller’s time as a doctor. Meanwhile, many of the performances aside from Gibson’s, namely those of the one-note villains, are the harsh, almost parodic, and over-the-top performances usually associated with exploitation cinema.

Bleak, fatalistic, and ultimately of questionable morals though this revenge story may be, Miller oversees an incredible technical showcase of inventive camera angles and fast-paced editing. The many car chases throughout the film require precise cross-cutting between the pursuer and pursued to create tension, and editors Tony Paterson and Cliff Hayes know the exact moments to cut away or linger to tie the audience in knots. The film’s high-velocity chases also require daredevil camera placement mounted on the cars themselves; the low, close-to-the-road angles are captured at top speeds by cinematographer David Eggby. The vehicular crashes are visceral and treat automobiles like paper, such as the sequence where an Interceptor bursts through a mobile home during a chase. More punishing is the care with which Miller depicts human violence. Gunshots, beatings, and rape all have an uncomfortable quality that aligns Mad Max with its B-movie roots, largely inspired by Miller’s time as a doctor. Meanwhile, many of the performances aside from Gibson’s, namely those of the one-note villains, are the harsh, almost parodic, and over-the-top performances usually associated with exploitation cinema.

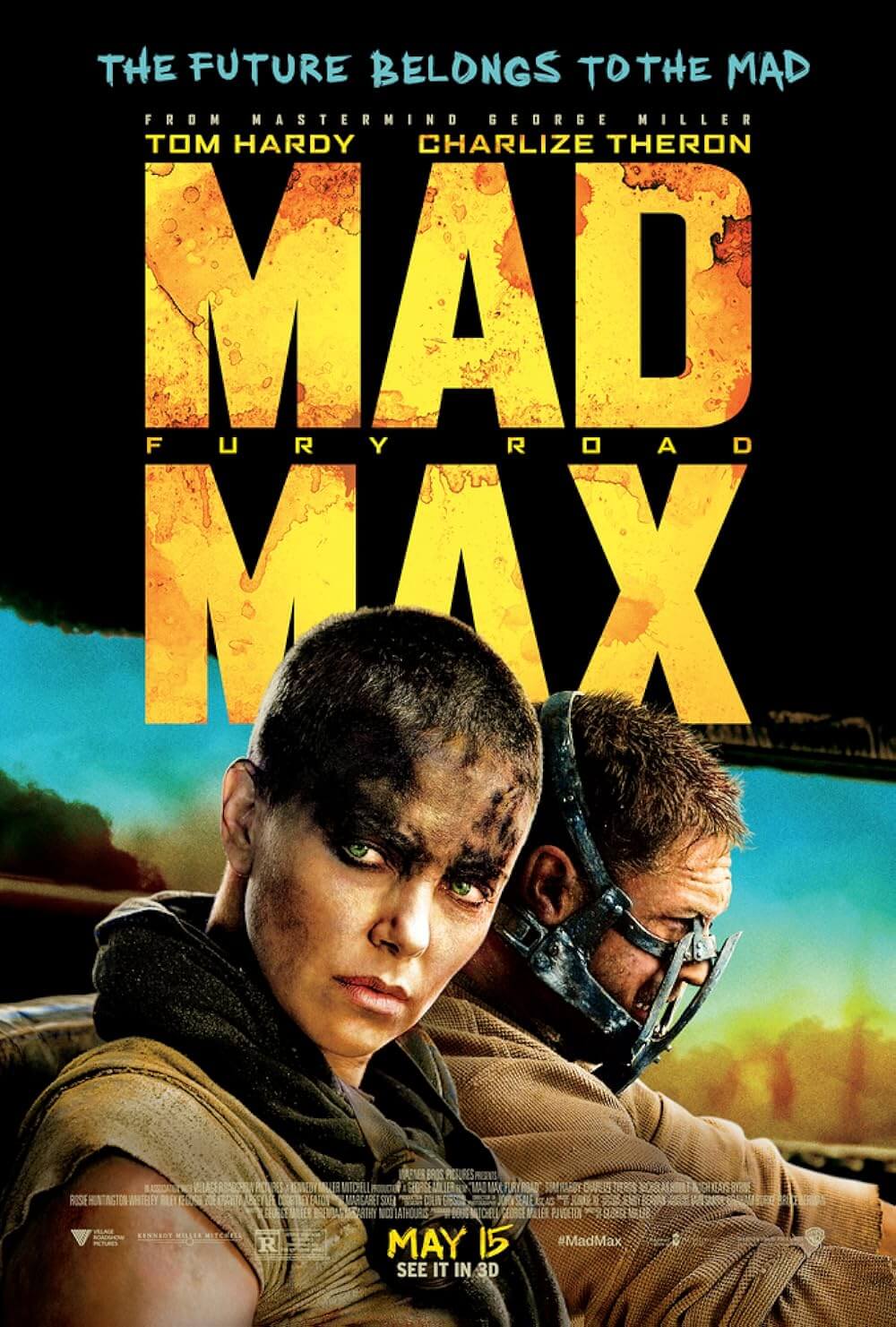

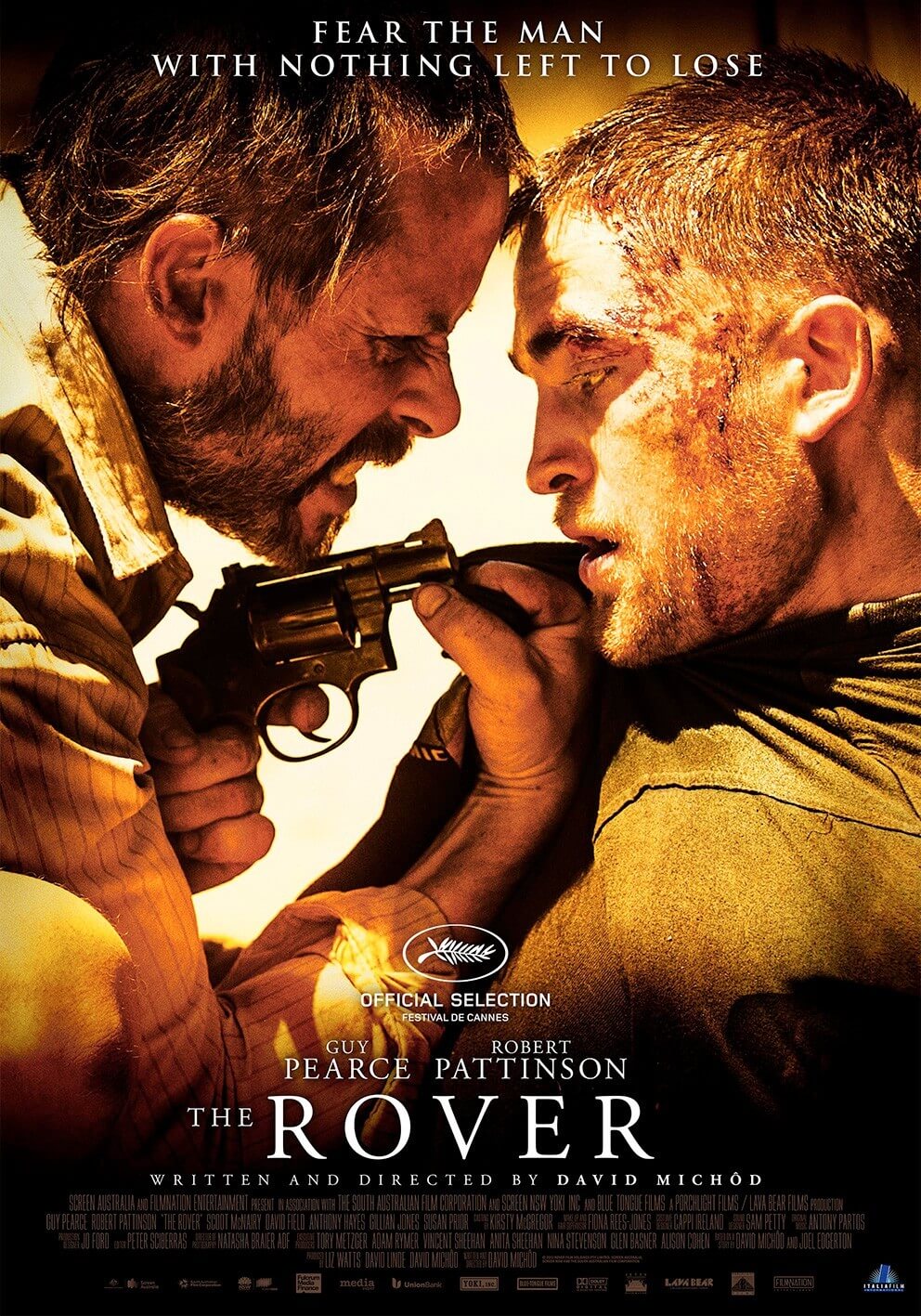

Although unoriginal and hindered by the lower trappings of its basic subject matter, Mad Max elevated itself by having something to say, and doing it in a way that was fulfilling both technically and dramatically. Countless knock-offs followed, particularly in the Italian post-apocalyptic subgenre, but also within Australian cinema. For every disappointment like Wyrmwood: Road of the Dead there is a picture like The Rover, where Miller’s influence shapes something wonderful. Here, Miller’s direction and Gibson’s admirable debut resulted in the beginnings of an iconic anti-hero. Revisiting the film after more than thirty years, the spare, unflinching nature of the story still delivers a considerable impact, even if the lesser performances and wanderous middle section distract. And as the sequels progressed, Miller’s dramatic arcs would become less engaging on an emotional level, but his production value and the purity of his adrenaline-infused experience would improve. Regardless of its uneven pacing in the middle and low-budget shortcomings, Mad Max represents a landmark for its director, star, and subgenre.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review