Lucy

By Brian Eggert |

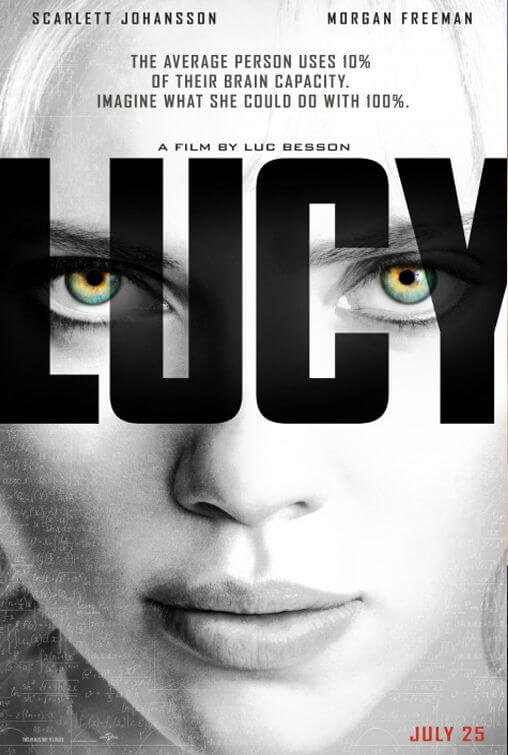

A film dependent on the myth that we use only 10 percent of our brain, and further driven by the notion of unlocking 100 percent of the brain’s potential, Lucy, by writer-director Luc Besson, taps into the possibilities more than Limitless, another story about the same subject, but succeeds only in delivering an emotionless action-thriller that wants to be smarter than it is. In the 1990s, Besson made some great action yarns with The Professional and The Fifth Element, though in recent years, he’s preferred to grandfather the next generation of action directors like Pierre Morel (Taken) and Olivier Megaton (Colombiana) by producing and often providing the scripts to profitable shoot-em-ups. With Lucy, he returns to the director’s chair for the kind of story to which he’s most attributed. And rather than blowing audiences away, he’s made a confounding picture that either explores his central idea too much or not enough; either way, it’s an unsatisfying disappointment.

Neither a convincing conflict nor well-developed characters inhabit Besson’s script, about an American tourist of average intelligence who, while in Taiwan, is kidnapped by a crime lord and forced to become a drug mule. Scarlett Johansson’s titular heroine finds herself under the gun of Jang (Choi Min-sik, from the original Oldboy), an imposing baddie who orders a pouch of an experimental drug called CPH4 sewn into her stomach, and into those of three other unwilling mules. After she’s transported into a shoddy cell, she receives a beating that unseals the pouch and sends the mystery drug coursing through her blood stream, electrifying her synapses in extraordinary shades of blue. As this goes on, Besson cross-cuts to a lecture by Samuel Norman (Morgan Freeman), an academic who speculates that things would get pretty out-there—telepathic control over matter, space, and time—should human beings ever gain control over 100 percent of their brain, which is exactly what happens to Lucy. The playful editing by Julien Rey also cross-cuts to nature scenes, such as a cheetah hunting a gazelle, to create a parallel between humans and animals, and demonstrate how far beyond basic primal human instincts Lucy will become.

The best scenes of Lucy occur early on, when there’s still some fragment of humanity left in Johansson’s performance, and her character is using 20 or 30 percent of her brain’s potential (Besson keeps track with a counter that flashes onscreen periodically). Lucy develops the ability to learn and perceive things we cannot imagine, and this transforms her into an unstoppable adversary for Jang’s band of thugs. These scenes where Lucy can out-fight and telekinetically outmaneuver gangsters remind us of Milla Jovovich running circles around alien goons in The Fifth Element. But before long, Lucy’s mental capacities increase and she quickly becomes aware that emotions are elementary functions and only hold us back from exploring our real potential. Here’s where the film begins to slow and we gradually lose any investment. It’s difficult to have sympathy for an already poorly drawn character who, now omnipotent, has no emotions and can do virtually anything she puts her mind to. It may have been more entertaining to preserve the early stage in Lucy’s development and wait until closer to the climax to unlock her full, emotionless potential.

The comparison to The Fifth Element is apt, as both films involve a supreme being who thwarts bad guys. What made The Fifth Element so engaging is that it wasn’t told from the supreme being’s perspective; rather, from that of her lovelorn protector (Bruce Willis). Besson introduces a similar role in Lucy with a Parisian cop Del Rio (Amr Waked), who serves as Lucy’s sidekick and whose scenes feel abridged. At one point, she kisses him as “a reminder” of her humanity; however, the moment feels like a forced attempt to emotionally invest the audience. At any rate, when Lucy begins reading minds and putting whole rooms of baddies to sleep with the wave of her hand, the cop becomes superfluous, and any attempt by Jang’s crew to stop her is devoid of tension when all it takes is a mere thought to defeat them. Meanwhile, Johansson’s character has more in common with her voiced OS in Her, who achieves transcendence through vast knowledge, while her emotionless performance echoes early scenes in Under the Skin, except without the inevitable dramatic payoff.

In the end, Besson’s script is involved in shoddy science propelled by the myth that we only use 10 percent of our brain. (Using EEGs, magnetoencephalographs, MRIs, and PET scans, neuroscientists have found no such dormant areas waiting to be uncovered. But who’s checking?) The myth was first proposed in a 1936 self-help book and has no basis in scientific fact, but still, the myth persists because, well, that’s what myths do. Nevertheless, Besson isn’t concerned with science and would rather enter the furthest reaches of exploratory metaphysics through imagery likened to The Matrix and The Tree of Life, where Lucy sees the world as endless streams of neurons and instantly taps into the vast reaches of space and time. It’s a fun idea, but Lucy never quite pays off in Besson’s usual popcorn-munching no-brainer terms, nor does he succeed in elevating the material to its highbrow possibilities. Indeed, Besson packs a lot of ideas into the brief 89-minute runtime, but he should’ve spent another 20 minutes on character development. And, to get as arbitrarily mathematical as his film, he’s only making use of about 65 percent of his concept’s potential.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review