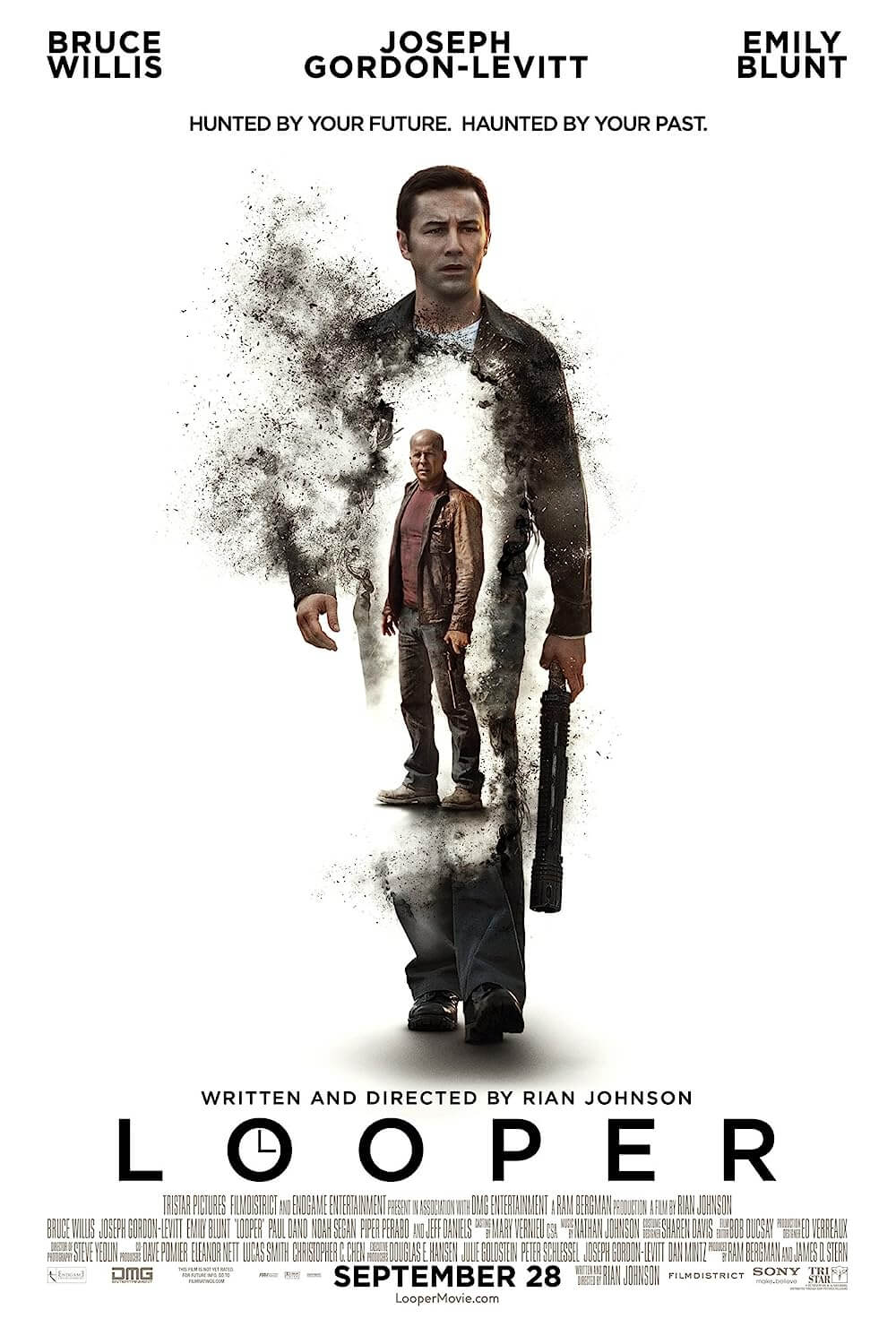

Looper

By Brian Eggert |

Explained in a gritty film noir voiceover style, The City in 2044 has been ravaged by poverty and overrun by crime. Vagrants and abandoned jalopies fill the streets of what might be Kansas City or Wichita, a crummy metropolis surrounded by farm fields and controlled by the criminal underworld. Here, ten percent of the population has developed meager telekinetic abilities and impresses each other by levitating coins, the extent of their talent. Time travel hasn’t been invented yet, but by 2070, a one-way system has been refined and outlawed, utilized only by the ruling criminal class who send their hits back thirty years where a “looper” kills them and disposes of all evidence. The looper waits at a specific time and place, and the victim suddenly appears hooded, hands bound, and kneeling; the looper fires his blunderbuss and collects his silver bar payday strapped to the victim’s back. Every once in a while, a looper finds a gold payday on the victim’s back, which means they’ve killed their future selves. This is called “closing the loop,” and with it begins a 30-year countdown to the looper’s own demise.

Every few years, a superior genre film comes along and retunes our expectations for what great science-fiction filmmaking should be. Rian Johnson’s Looper belongs on a shortlist of monumental sci-fi pictures that are imaginative, thoughtful, emotionally involved, and never predictable. Along with Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report, Richard Linklater’s A Scanner Darkly, and Christopher Nolan’s Inception, Johnson’s film contains a carefully considered future world that seems plausible and matter-of-fact. The setting isn’t approached with a sense of faux wonder. His characters are a part of their world; they know its limitations, and they are not impressed by its clunky hoverbikes and eye-drop hallucinogens. As a film about time travel, Johnson considers the paradoxes inherent to rules he establishes, described in clever detail, and never violated by the turns in his story. The implications are clear without his characters engaging in unnatural exposition by “making diagrams with straws.”

In this world, anti-hero looper Joe Simmons (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) kills for a living, having been recruited at a young age by Abe (Jeff Daniels), a crimelord sent back from the future to manage loopers. Joe spends his days wiping the future’s human garbage from the timeline and his nights on drugs and bedding prostitutes. He’s not a very nice guy; however, this lifestyle is wearing on him. Although he’s one of the best, Joe makes a mistake by harboring a fellow looper on the lam. Nervy and helpless, Joe’s friend Seth (Paul Dano) faced his older self on the looper slab and couldn’t pull the trigger. Now Old Seth is running free, and Abe wants Young Seth dead for the trouble. Many loops like this have been closed as of late, the future’s top crimelord, known only as “The Rainmaker,” apparently cleaning house. Not long after Seth’s demise, Joe experiences the same face-to-face conundrum when Old Joe (Bruce Willis) appears before him; except, unlike the future’s other victims, Old Joe’s hands aren’t tied, and his head isn’t hooded. The Joes look into each other’s eyes for a moment of recognition that allows Old Joe to take advantage of his younger self’s hesitation and escape.

With this, Johnson shifts the perspective. Now the film proceeds from Old Joe’s viewpoint, and we see what the future would hold for Young Joe had he actually closed his loop and spent the next 30 years living off the gold bar rewards. He moves to Shanghai, where drugs and crime rule his life until Old Joe finally meets a Chinese woman (Qing Xu); she cleans him up and saves him. They fall in love and settle down. Life is perfect. Until, of course, the future’s crimelord, The Rainmaker, sends him back in time to be assassinated by his younger self. Old Joe would do anything to maintain his perfect version of his future, and so dropped in 2044, he sets out to find and execute The Rainmaker, who would only be a child in that time. In a plot point similar to The Terminator, Old Joe tracks down three possible children that might be The Rainmaker, who, once dead, will be unable to break up his happy future existence. However cruel it might seem, think of it this way: If you could travel back to the year 1900 and gun down the 10-year-old version of Adolf Hitler, wouldn’t you do it?

With this, Johnson shifts the perspective. Now the film proceeds from Old Joe’s viewpoint, and we see what the future would hold for Young Joe had he actually closed his loop and spent the next 30 years living off the gold bar rewards. He moves to Shanghai, where drugs and crime rule his life until Old Joe finally meets a Chinese woman (Qing Xu); she cleans him up and saves him. They fall in love and settle down. Life is perfect. Until, of course, the future’s crimelord, The Rainmaker, sends him back in time to be assassinated by his younger self. Old Joe would do anything to maintain his perfect version of his future, and so dropped in 2044, he sets out to find and execute The Rainmaker, who would only be a child in that time. In a plot point similar to The Terminator, Old Joe tracks down three possible children that might be The Rainmaker, who, once dead, will be unable to break up his happy future existence. However cruel it might seem, think of it this way: If you could travel back to the year 1900 and gun down the 10-year-old version of Adolf Hitler, wouldn’t you do it?

In a stroke of genius plotting, Johnson shifts perspectives again to a Kansas farmhouse, where single mother Sara (Emily Blunt) lives with her son Cid (Pierce Gagnon), the boy being one of the children on Old Joe’s hit list. Young Joe, now on the run from Abe’s goons and hunting Old Joe to restore balance to his own life, hides out in Sara’s cane fields and gradually becomes a trusted friend. Just as we can sympathize with Old Joe’s mission to save the world from the Rainmaker’s cruel hand, we can understand when Sara argues that she will raise Cid, possibly The Rainmaker, to do good with his staggeringly powerful telekinetic abilities, instead of the malevolence he seems destined for. Now we question the logic of killing young Hitler. Why not simply raise him to be a better person? Throughout the film, Johnson toys with our sympathies and confronts our understanding of the usual time travel motives, so by the climax, we’re engaged in the objectives of each character. And yet, when the conclusion at last arrives, it’s such a pitch-perfect and satisfying finish that we couldn’t imagine it ending any other way.

Johnson’s marriage of hyperrealism and high-concept sci-fi elements feels like a natural progression in his career, from his debut with 2005’s high-school noir Brick to his Mamet-inspired con-movie The Brother’s Bloom in 2008. Adopting Philip K. Dick-worthy genre consideration, Johnson again incorporates Raymond Chandler-style complexity into his noir-tuned narrative, whereby the turns keep us guessing but also never devolve into futurist wonderment. Unlike something like Star Trek or Avatar, in which we’re intended to sit back in awe of the production designer’s formation of this future world, Johnson takes careful steps to integrate us. For example, to make the transition from Gordon-Levitt to Willis a believable one, the younger actor wears subtle makeup prostheses to reshape his nose and mouth. Along with this, Gordon-Levitt’s half-smirks create an, at times, uncanny resemblance to Willis. It’s also a testament to the younger actor’s willingness to lose himself in a role, whereas an actor with less integrity may have wanted to save face to assure his audience can recognize him.

The film’s acting is superb, in part because Johnson’s characters have such intricate descriptions while his scenario pulls our sympathy in multiple directions at once. Gordon-Levitt goes from criminal hero to self-serving villain to compassionate family man, every transition natural within the story. His range in material from The Lookout to 50/50, and then in actioner roles like this year’s underseen Premium Rush continues to expand and impress, while it’s all encapsulated here. Willis, returning to time travel after his part in Terry Gilliam’s decisive take in 12 Monkeys, also returns to credible, non-self-referential acting. As of late, his career has been bogged down by ironic performances in Cop Out and The Expendables 2, but the Die Hard star proved twice in 2012 that he’s still a viable screen presence—first in Moonrise Kingdom and now Looper. To see Willis in an actionized role that doesn’t require him winking at the screen is a real treat. Blunt lends the emotional center of the piece, whereas Gagnon, creepy yet uncannily sophisticated, shows the presence of an actor far beyond his years. Dano is so good in his brief scenes that one wishes his character had survived a little longer before his shocking demise.

The film’s acting is superb, in part because Johnson’s characters have such intricate descriptions while his scenario pulls our sympathy in multiple directions at once. Gordon-Levitt goes from criminal hero to self-serving villain to compassionate family man, every transition natural within the story. His range in material from The Lookout to 50/50, and then in actioner roles like this year’s underseen Premium Rush continues to expand and impress, while it’s all encapsulated here. Willis, returning to time travel after his part in Terry Gilliam’s decisive take in 12 Monkeys, also returns to credible, non-self-referential acting. As of late, his career has been bogged down by ironic performances in Cop Out and The Expendables 2, but the Die Hard star proved twice in 2012 that he’s still a viable screen presence—first in Moonrise Kingdom and now Looper. To see Willis in an actionized role that doesn’t require him winking at the screen is a real treat. Blunt lends the emotional center of the piece, whereas Gagnon, creepy yet uncannily sophisticated, shows the presence of an actor far beyond his years. Dano is so good in his brief scenes that one wishes his character had survived a little longer before his shocking demise.

Looper is the kind of film that only comes along every so often. It’s cerebral yet filled with substantial dramatic pull, exploring both brainy scientific theory and multidimensional characters with equal levels of inspection and inventiveness. Johnson’s treatment contains a maturity and energy that displays the trappings of a confident filmmaker pouring his talent into every subtle science-fiction detail, every sharply deliberate camera movement, and every emotional progression of his characters. The high degree of verisimilitude on display is counteracted by Johnson’s refusal to get caught up in meaningless sci-fi flourishes, resulting in a film whose drive is as singular as its compelling narrative. This is all compounded by the story’s surprising humanism, which binds us to the material and engages us in unexpected ways. Finally, in every respect, it’s an exciting and rewarding motion picture experience, one that will leave its audience buzzing long afterward and desperate to see again. In short, Looper is a visionary film and an instant classic.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review