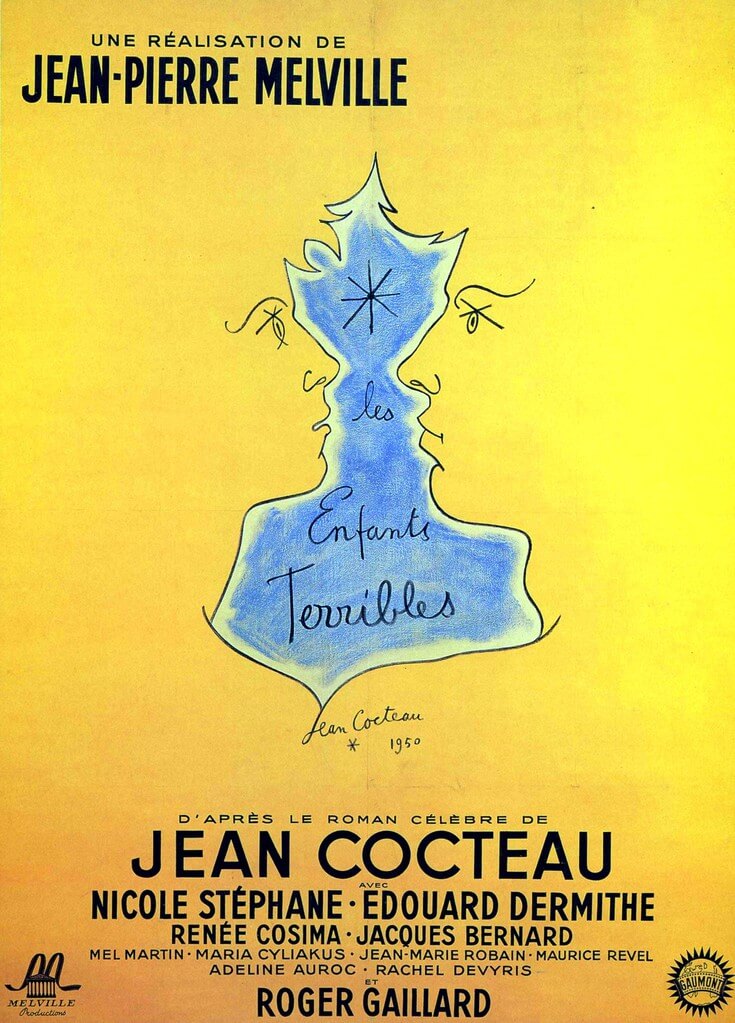

Les enfants terribles

By Brian Eggert |

For cinephiles whose only out is DVD or the occasional revival theater showing for their much-needed dosage of French film, Jean-Pierre Melville might seem exclusive to fatalistic and philosophical crime pictures. The Criterion Collection, along with American pop-culture icons Quentin Tarantino and John Woo, have seen to it that Le cercle rouge, Bob le Flambeur, and Le samouraï among others, have grown in Western popularity, lending to the idea that Melville means gangster. All these movies contain a foggy sort of mood as if comprised, in part, of shadows; characters float, simply existing onscreen as a presence, often as ambiguous as mist and yet wholly elemental as such. The auteur’s stereotyped filmic persona, unfortunately, ignores his non-crime work, most recently appreciated in my essay on Mellville’s Army of Shadows posted in The Definitives. But not until I viewed his second feature film, Les enfants terribles from 1950, did I realize the director’s vast range as an artist and filmmaker.

Based on Jean Cocteau’s 1929 novel, the script for Les enfants terribles was written by Cocteau himself, into a virtual carbon copy of his novel. It centers on Elizabeth and Paul, a wild sister and brother pair who live alone with their aged mother. Elizabeth (portrayed in a tour de force performance by Nicole Stéphane) maintains control of the household, or rather her world, which consists of her shared room with her brother. She’s a fiery, blatant young woman, overpowering her effeminate brother Paul (Edouard Dermithe). Paul seems delicate, and his delicacy is blazed over by his sister, who encourages his manic, melodramatic behavior. Together, the two are like sexualized children, collecting trinkets they call “treasures” and completely enclosed in their own world—their room. Inseparable, their mutual space is cluttered like a mental patient’s, complete with a Duchamp-esque statue of a woman featuring a painted-on mustache; on their mirror, the words “suicide is a mortal sin” are written, alluding to their self-destructive natures.

Between insulting each other and playing mind games, Elizabeth and Paul are near incestuous in their sibling intimacy; physical contact is somewhere between that of brother and sister and flirtatious lovers. After Paul is hit with a rogue snowball at school in the beginning of the film, he finds himself bedridden with Elizabeth caring for him. The doctor advises rest, saying it’s serious but not serious. Others seem to consider the siblings sick or off somehow, avoiding the duo at all costs. What friends they do have are tortured as outsiders, particularly by Elizabeth, who is the emotional victor of the two’s never-ending mêlée of emotions. Their end builds, residing somewhere in between the star-crossed lovers of Romeo and Juliet and the murderous friends from Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures. Cocteau himself narrates the picture, pointing out how they are “like two members of the same body.” Their growing tension, growing jealousy, and growing cruelty are the stuff of David Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers, where a deranged familial connection swings out of control, ultimately destroying both parties—which are at last one and the same.

Melville always regretted casting Edouard Dermithe in the role of Paul. And, perhaps, Dermithe wasn’t the best choice, as he looks like a thirty-year-old playing schoolboy. Dermithe is bulky, a physically large man, and Paul may have been better suited by an actor capable of daintiness. Of Dermithe, who was also a noted painter, Melville would say, “I would much rather have had one of his paintings than have him in my cast.” Nevertheless, Dermithe’s size provides an interesting irony, accentuating the awkwardness of Paul’s understated and indeterminate sexuality. Other production troubles ensued. Cocteau attempted control over the production, it being his book and Cocteau being a director himself—he directed possibly the best available version of La Belle et la bête (The Beauty and the Beast, 1946). Having just finished Orphée (Orpheus, 1950), Cocteau was visiting Melville’s set one day and inadvertently called “Cut!” From that point on, Melville was careful not to allow Cocteau any creative control over what Melville saw as his picture, written by Cocteau or not. Though great friends prior to filming, the production wore on Cocteau and Melville’s relationship as nearly every major decision became an argument. Melville wouldn’t budge.

Melville chose Baroque music to match the baroque narrative. Bach and Vivaldi add to Elizabeth and Paul’s fanciful nature, to their expected air of frivolity amidst stirring emotion. Justified and as spiritual as the film’s characters, the music serves as a cultural springboard and an emotional tempo for the sibling pair, allowing their unique relationship class rather than focusing on otherwise strange truths. Cocteau wanted jazz music to accompany his story, which may have trivialized their relationship, underscoring their eccentricities to unsympathetic levels—even to the point of being completely random and frenzied. The viewer, in this case, may have been forced to examine what the jazz music pointed to; an unhealthy relationship. Bach and Vivaldi, on the other hand, stress Elizabeth and Paul’s unwholesome qualities, but also make their more tender moments bittersweet.

Melville’s fluid camera movements flutter around with as much orchestrated mania as the film’s stars. The story itself challenges traditionalism, represented by authoritative presence—in the form of the school, the doctor, the nurse, and so on—through its wholly untraditional main characters, Elizabeth and Paul. This sister and brother are the antithesis of normality, of stabilized society; neither lives a life of regularity nor even a typical rebel life. Melville’s camera captures that, as his direction often shifts depending on the material. In a more static film, for example, his last picture Un Flic, his camera is mostly stationary, as are his pensive characters. Les enfants terribles involves staccato dialogue, often spoken with furious intensity by Stéphane; his camera reacts to her, swirling around or bounding with virtuosity overhead.

There is no doubt this is a Melville film, despite any influence Cocteau attempted to assert. Melville’s ever-present theme of fatalism can be seen early on in the mirror in Elizabeth and Paul’s bedroom. “Suicide is a mortal sin” alludes to their deaths in the final frames of the picture. Death is usually welcomed by Melvillian characters, as they’re frequently plagued by the director’s own poetic affection for the death drive. Here is no exception, as both Elizabeth and Paul seem fateful if not somehow dramatically determined to commit suicide in their final scenes. So many great Melville characters throw themselves into chance, and, save for Bob le Flambeur, usually come out on the bottom.

What a unique picture this was, gushing with emotion rarely seen in Melville’s filmography. Now that The Criterion Collection’s new DVD has been released, Melville fans, whose only exposure to one of France’s great directors has been Criterion’s four other Melville editions (Army of Shadows, Bob le Flambeur, Le cercle rouge, and Le samouraï), can expand their horizons as I now have, visiting his expertly conceived emotional side. Critics were split upon Les enfants terribles’ initial release, noting that its plot is grotesque with homosexual and incestuous undertones. As Melville’s career progressed and his auteur status solidified, the film gained prestige. Francois Truffaut is famous for saying, in this often-quoted praise, “Jean Cocteau’s best novel became Jean-Pierre Melville’s best film.” While Truffaut was perhaps overzealous about this picture, it’s hard to blame him for loving it.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review