Ema

By Brian Eggert |

Chilean director Pablo Larraín is one of today’s most compelling filmmakers. After his debut on Fuga (2006), about a composer who goes mad, he began his career with a trilogy of films set during the politically turbulent era of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship of Chile from 1973 to 1990. Each film features its protagonist grappling with some aspect of Pinochet’s takeover or time as leader. In Tony Manero (2008), a character resorts to murder to realize his dream of becoming a Saturday Night Fever persona; Post Mortem (2010) takes place against the military coup of former President Salvador Allende; No (2012) dramatizes the advertising spin used to remove Pinochet from power in the 1988 election. Each film is rich with symbolism that reflects the violence of the regime. Larraín has since branched out and explored other genres and political periods, including Neruda (2016), his twisting account of poet Pablo Neruda’s escape into the Andes after the Chilean government turned against Communists in 1946. With Jackie (2016), the director’s first English-language film, Larraín reinvigorated the biopic with an effective, nonlinear, and layered structure that elevated the material. He continues to test his boundaries of style and narrative with Ema, a film that has very little in common with the filmmaker’s earlier work.

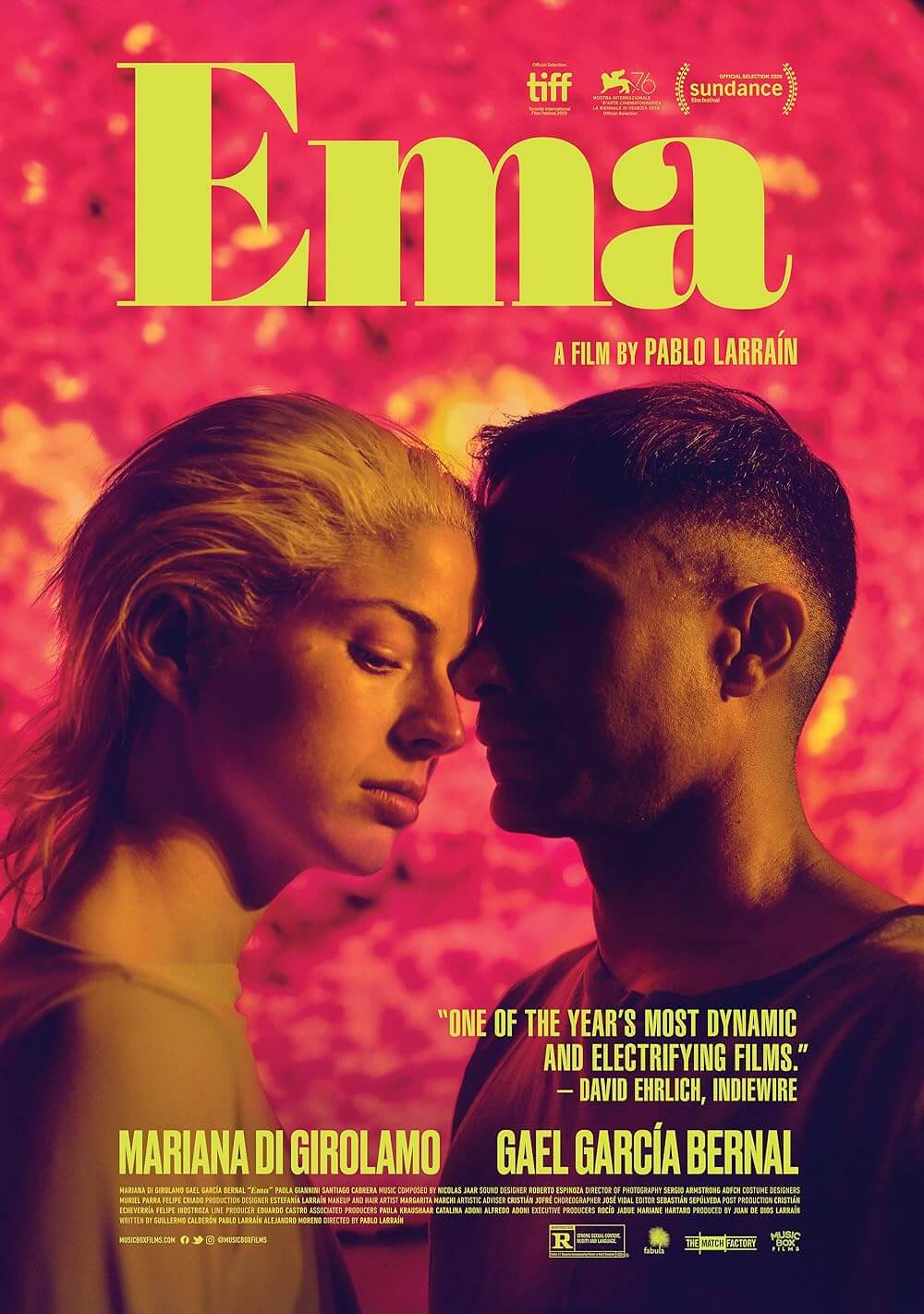

For starters, Ema takes place in modern-day Chile and features a woman at the center, two rarities in the director’s cinema. The titular character is played by Chilean soap star Mariana Di Girolamo, who embodies the mercurial Ema, an unpredictable main character with a head of bleached, slicked-back hair. Ema teaches dancing to children, has a passion for reggaeton, and performs in a troupe choreographed by her husband Gastón (Gael García Bernal). She also enjoys strapping a flame-thrower to her back and torching vehicles and traffic lights, or just spraying fire into the sky. Her marriage to Gastón recently became toxic after they gave back their adopted son, named Polo (Cristián Suárez), following a violent incident involving Ema’s sister and Polo’s penchant for fire—and there’s some question as to whether the event was accidental or not. Maybe Ema and Gastón’s marriage was always troubled. She berates him for being unable to give her a child (she calls him an “infertile pig” and a “human condom”). He confronts her unconventional parenting style (“My son can suck my whole body if he wants,” she defends), then mocks her with Polo’s final words as they returned him to Child Protective Services (“Please Mommy, no. Don’t leave me,” Gastón taunts in a child’s voice).

Each aspect of Ema’s personality and life has been assembled in the editing room by Larraín and Sebastián Sepúlveda. The production shot without a traditional script, without a grand vision assigning every detail a purposeful meaning. Rather than making Ema feel scattershot or uneven, this approach imbues the film with an essential, disorienting sense that keeps the viewer struggling to maintain balance, like standing on a tightrope. As improvisational as that technique may sound, the film gradually reveals more about Ema, to the extent that as soon as Ema ends, the viewer feels compelled to immediately start it again with the new information we’ve learned, now in context. The film’s layered quality adds to the character in scene after scene, but it also contains a Pandora’s box of mysteries and wild components to Ema’s personality, revealing Larraín’s overwhelming interest in the unanswerable complexities of human beings. Toward the end, just when the viewer thinks they have a handle on Ema and what drives her, Larraín inserts a horrifyingly ambiguous final shot that raises questions about everything we’ve just seen.

Shot in the city of Valparaíso, the film unfolds in the aftermath of Ema and Gastón giving Polo back after having him for just a year. Co-writers Guillermo Calderón and Alejandro Moreno, who worked with Larraín to develop the screen story, implant questions about Ema’s relationship with the six-year-old boy. We learn that he shared characteristics with his adopted mother, including exhibitionism, an intense relationship between mother and child, and an interest in pyromania. And yet, there’s an urgent need for motherhood in Ema, and each of her actions becomes another step toward attaining that status. Her intimate affair with divorce lawyer Raquel (Paola Giannini) might seem a natural progression after her relationship with Gastón falls apart; however, it shows signs of an elaborate plot when she also beds Raquel’s husband (Santiago Cabrera). At one point, when Ema cajoles her way into a teaching job, a friend tells her, “You’re close.” To what? Many of Ema’s choices seem impulsive, such as her occasional fling with a fellow dancer. Or maybe every choice fits into a larger scheme.

Di Girolamo is brilliant and unflinching in the role, playing a character who cannot easily be summed up as either wholly intentional or driven by random impulses. Ema seems motivated by both an agenda and her desires, and unlike many classical film characters, the conflicting aspects of her personality do not easily resolve themselves. She’s a mass of contradictions, both scary in her freedoms and admirable for them, both diminutive in stature and yet wholly imposing. Larraín grants the viewer just enough time in her headspace—punctuated with more than one almost directly into the camera looks—to maintain our empathy for her, despite what might be considered an irresponsible approach to parenthood (a social worker tells Ema and Gastón, “The system is made to weed out people like you.”). He also immerses us in Ema’s fluid dancing. An extended sequence late in the film transfixes the viewer in a frenetically shot, boldly confrontational series of dances that must be felt and not over-intellectualized. That also applies to a montage of sex between Ema and several partners, where the connection she has to each remains undeniable, even if her behavior confronts certain mores about monogamy.

Ema is not without its remarks about more significant issues—the divides between generations, classes, and even races, as Larraín’s earlier films have explored. Many of these themes emerge in the difference between Ema and her husband, and how they express themselves. Gastón remarks about his disdain of Ema’s beloved reggaeton as a lower form of dance to his more traditional style, partly because it depends on feeling rather than the organization of Gastón’s instruction (its “hypnotic rhythm turns you into a fool,” he complains). He comes from a higher class and twentieth-century mold, and he expects his dancers to perform in a manner he dictates. But Ema comes from a younger generation of dancers who feel their way through ephemeral performances. For them, reggaeton is no different than sexual liberation—both are acts of self-expression through bodily freedom. Gastón, ever in control, condemns such freedom as undisciplined, mindlessly youthful, even irresponsible. His views carry over into a subtle form of racism. Polo is of Columbian descent, and Gastón maintains certain prejudices about the boy’s “native” lineage, a familiar perspective of Euro-centric elitism in Latin American countries.

Similar to Larraín’s construction of his main character, his formal approach to Ema contains equal measures of randomness, feeling, and intentionality. This being his most modern film in terms of setting, his approach borders on postmodernism, particularly in the editing style. There’s a discordant quality to the arrangement of scenes that jump from one moment to the next without a clear progression or logical building from scene to scene, leaving the viewer to appreciate the film’s structure only afterward, even as its propulsive energy carries us through. It’s also Larraín’s most colorful and visually diverse film, as his longtime cinematographer Sergio Armstrong breaks from the controlled palettes of the director’s earlier work for something accented in the colors of dance clubs, glowing neon, and domestic spaces. Nicolas Jaar’s music, too, conforms to Ema’s bright nonconformity of styles. At any moment, the film and its character might seem to be erratic and falling apart at the seams, yet there’s a complicated system at work that is both volatile and beautifully composed.

If there’s an image that epitomizes Ema, it’s the Sun. When the film opens, she’s dancing in Gastón’s troupe, performing in a piece based on José Luis Vidal’s “Rito de primavera” (“Rites of Spring”). A group of dancers moves in unison against a projection of the Sun, and their silhouettes progress around Ema, the center of gravity of both this dance and the film as a whole. To be sure, her roles include mother, daughter, wife, lover, and sister—she’s an all-encompassing character around whom everyone else revolves. Larraín has described her in interviews as a “Mother Nature” figure, a cruel and loving personification of nurturing and tough love. There’s an intangible logic, then, to her behavior and desire to “burn in order to sow again,” just as Nature must destroy to maintain a healthy balance. It’s the same order of the Kantian sublime, the primal force of viciousness and splendor. Larraín has discovered this symbol in the most unlikely of places and characters, but in doing so, he has made his best film to date. Whereas control and reflection have driven his earlier work, Ema feels like the work of a filmmaker at his most passionate and energized, and it’s an invigorating experience to behold.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review