Dead Man’s Wire

By Brian Eggert |

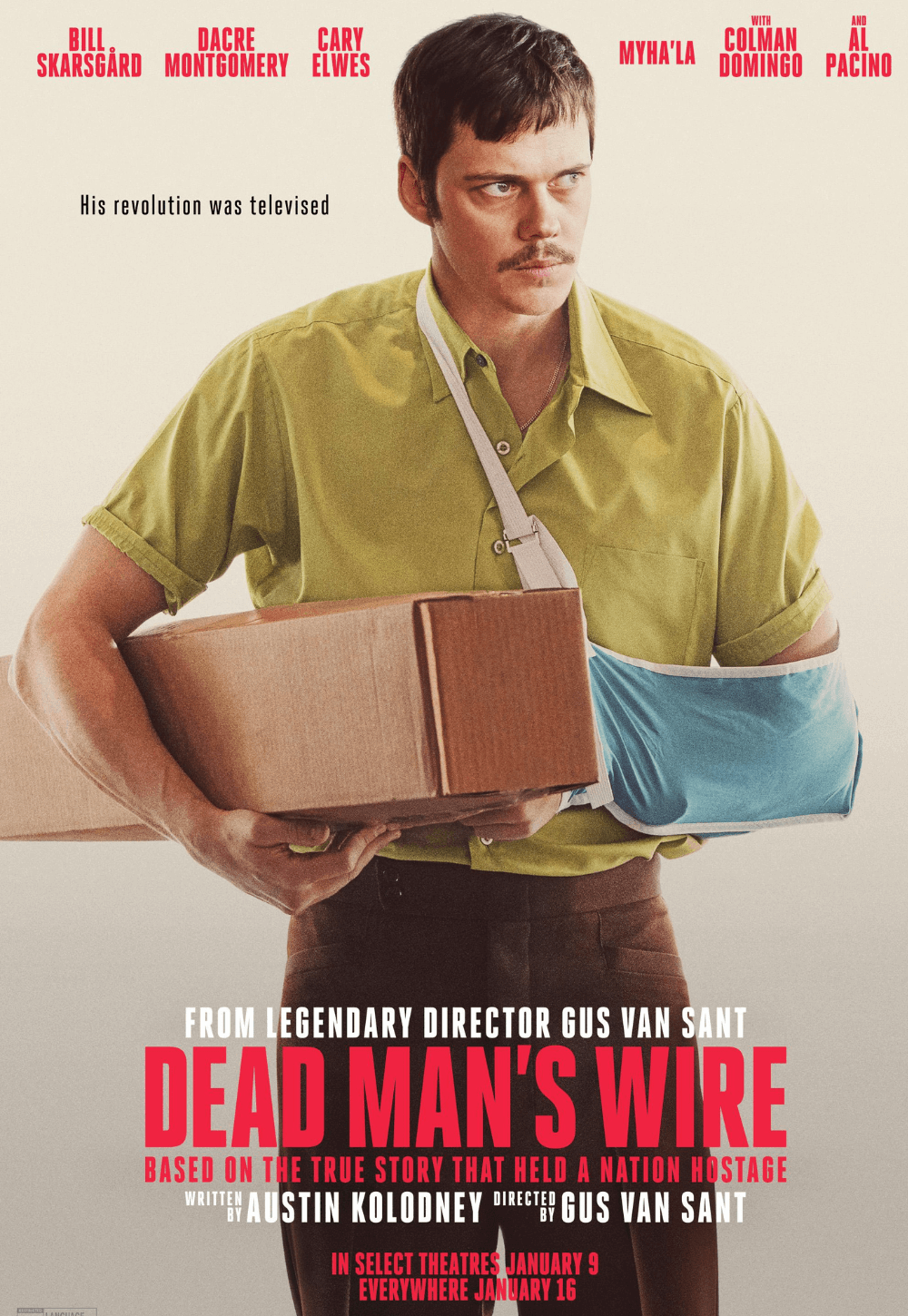

Little about Dead Man’s Wire—Gus Van Sant’s first feature since 2018’s underwhelming biopic, Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot—would indicate he directed it. But what does it mean to be a “Gus Van Sant movie” in the twenty-first century? He had an excellent string of artistic and some commercial successes in the aughts, from Gerry (2002) to Elephant (2003) to Milk (2008). His output in the 2010s was mostly disappointing, if occasionally awful (check out 2015’s The Sea of Trees). The director seems to be floundering, unable to find material that resonates with his voice and brings out what makes his best films so exceptional. Will he ever make another Drugstore Cowboy (1989), My Own Private Idaho (1991), or To Die For (1995)? In today’s market, where even renowned filmmakers struggle to get either mid-budget or independent pictures made, Van Sant has resolved to make a completely banal thriller about a real-life kidnapping that made headlines.

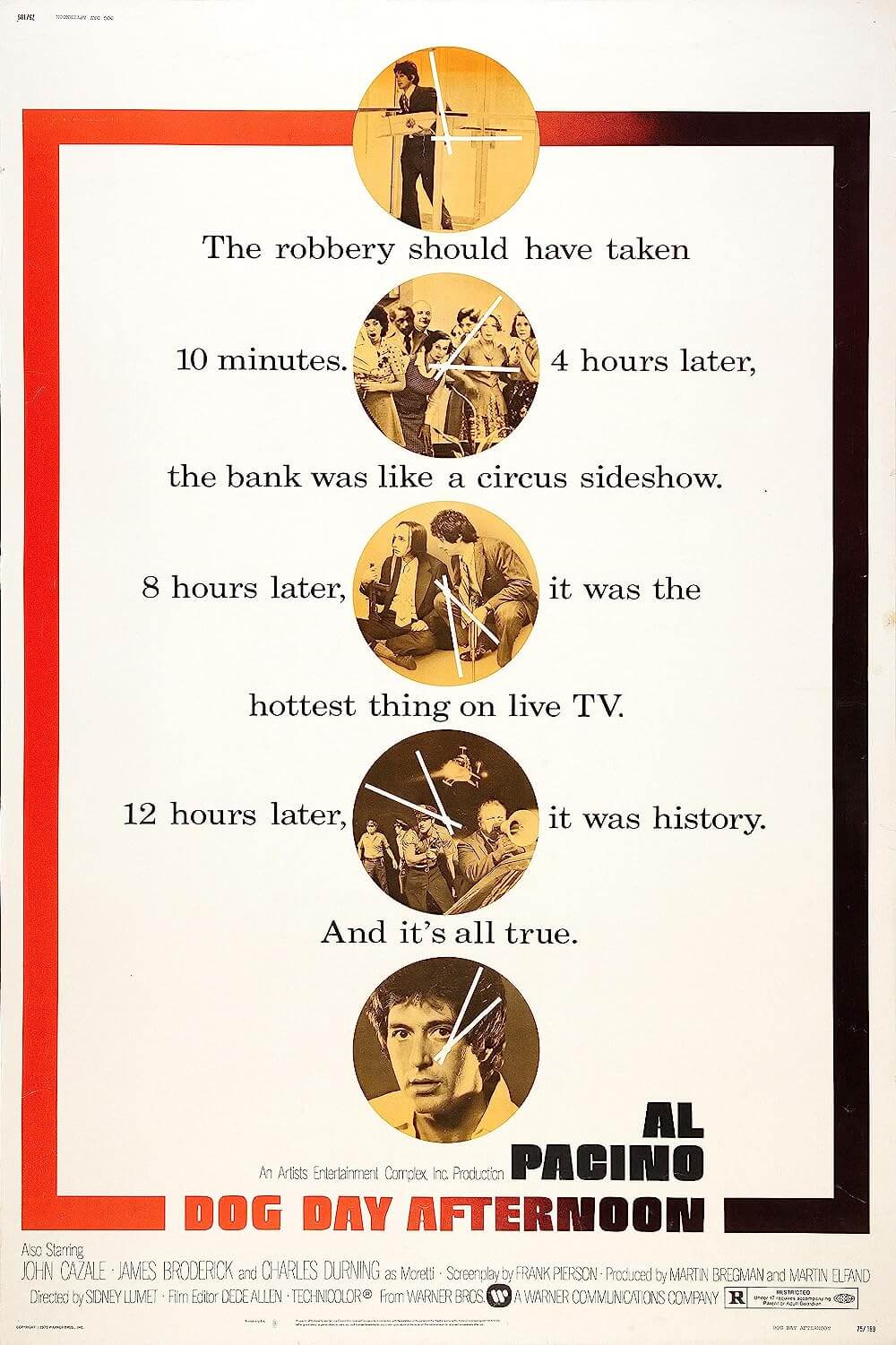

Working from a script by Austin Kolodney that feels inspired by the tone of Dog Day Afternoon (1975), Van Sant tells the story of Tony Kiritsis, an Indianapolis man who, in 1977, took a mortgage company executive hostage for a 63-hour standoff that made national news. Bill Skarsgård plays Tony, who was undercut on a lucrative deal by shady mortgage company owner M.L. Hall (Al Pacino). Tony wants an apology and financial compensation. So he resolves to kidnap the exec, using a sawed-off shotgun with a wire looped around the trigger and both of their necks, ensuring that if anything happens, the hostage dies. The problem: on the day Tony intends to carry out his plan, M.L. is on vacation in Florida, complaining that the chef cut his burrito in half and not in thirds, the way he likes it. Tony resolves to take the owner’s son, Dick (Dacre Montgomery), instead.

Following the typical kidnapping movie formula, there’s a cross-section of peripheral characters who gather outside after Tony brings Dick to his apartment complex. Inside, Tony sits his hostage at the kitchen table with the gun positioned in his face. Outside, the local cops, including Tony’s friend Det. Michael Grable (Cary Elwes, almost unrecognizable under a brown beard and wig), gather and attempt to negotiate. There’s also a young broadcast news journalist (Myha’la) hoping to get her big break with this story. Tony eventually calls a local radio disc jockey, Fred Temple (Colman Domingo), to air his reasons for the kidnapping, forcing Fred to serve as a reluctant conduit between Tony and the authorities. All of these characters have one or two dimensions at most, making their interactions seem superficial—especially Tony, whose abrasive personality ranges from angry to desperate for the spotlight.

Skarsgård’s performance and the character he plays are unpleasant, even though the movie frames Tony as a sympathetic figure next to the private equity predators at the mortgage company, which he calls the “biggest devils there are.” One can hardly argue with this take, but Tony is also a hothead, a showboat, and eager for media attention to satiate his ego. When he finally gets on camera, he declares himself a “goddamn national hero.” It’s made all the more jarring by the curious affectation in Skarsgård’s voice for the character, along with a little mustache that the original Tony didn’t have. To be sure, Skarsgård looks nothing like the real guy—seen in the now-standard actual footage shown over the end credits—who might’ve been more accurately played by ‘90s-era Joe Pesci or Danny DeVito. Likewise, Montgomery looks about twenty years too young to play the real Dick Hall. Doubtless, the producers wanted a young, popular cast to play the lead roles, rather than the less glamorous reality.

The formal execution feels just as forced as Skarsgård’s every line reading. Van Sant and cinematographer Arnaud Potier deliver a believable 1970s look and color palette, supported by some convincing period production design by Stefan Dechant. But the director and his editor, Saar Klein, infuse the movie with inconsistent stylistic flourishes that prove distracting. Several freeze-frame shots—some in color, some in monochrome—seem to indicate a still photographer on the scene, yet none is visible. A similar technique suggests a news crew on the scene, shooting in grainy video, yet the diegetic cameraperson is nowhere to be seen. Then, in a climactic moment, Tony is in court after the ordeal, and Van Sant shows Fred Temple watching the verdict on live TV. Based on the image on Fred’s television, a cameraman in the courtroom appears to be about two inches from Tony’s face, yet scenes in the courtroom show no such cameraperson.

Many of these details might go unnoticed if the unfolding story had pulled me in, but Dead Man’s Wire has only a surface-level interest in its characters and proves ham-fisted in its unmistakable, if meritorious commentary. Sure, it’s cathartic to see predatory capitalists receive their comeuppance, especially in today’s America, even if their public shame results from a disgruntled and stubborn nutcase who deludes himself into believing that he can negotiate his immunity, plus $5 million in compensation. Alas, as much as I was rooting against the mortgage company, Van Sant and the miscast Skarsgård never make Tony Kiritsis sympathetic enough to root for him. Somehow, Dead Man’s Wire feels like the most incompetent picture in Van Sant’s career on multiple levels, but most glaringly in dramatic and structural terms.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review