Coma

By Brian Eggert |

“Beware of the dreams of others, because if you are caught in their dream, you are done for.”

– Gilles Deleuze, philosopher and film theorist

An achingly personal expression, Bertrand Bonello’s Coma inhabits the fever dreamscape of COVID-19 lockdowns, presenting them in an abstract meditation on the aimless and surreal alienation experienced by many. Taking the form of an open video essay to Bonello’s then 18-year-old daughter, Anna, to whom he had dedicated Nocturama (2016), the film comes bookended with onscreen text to her. Most teens who spent some of their formative years in quarantine during the pandemic went through severe social withdrawal, seeing the isolation as a veritable death sentence of anxiety, frustration, and unused hormones. Bonello captures the array of emotions in a mixed-media project confronting the despair and uncertainty of what felt like an eternity in detention. Bonello acknowledges the most difficult lows and despair Anna seems to have experienced, and even so, provides a glimmer of hope for the future. After its debut at the Berlin Film Festival and subsequent release in France in 2022, the film finally arrives in the US courtesy of Film Movement. However, watching Coma in 2024, after the pandemic has subsided and our collective headspace has returned to relative normality, feels like having an acid flashback or opening a time capsule from a particular moment in early 2021.

When Bonello’s plans to make The Beast were stalled for a year due to conflicts with Léa Seydoux’s schedule, a producer convinced the French writer-director to make a short film while he waited. But Bonello resolved to complete a feature-length production using a short film’s budget and under strict quarantine protocols, resulting in this 82-minute project that borders on non-narrative and could function as an art installation in a museum. Then again, perhaps a museum or even a movie theater is an inappropriate place to screen Coma, given its subject matter. Maybe the perfect place to watch it is your home theater or laptop—wherever you spent most of your time watching movies during quarantine. Returning to the lockdown frame of mind is, naturally, unpleasant. And few movies that take place during COVID-19 have done that well, the exceptions being Rob Savage’s Host (2020) and Radu Jude’s Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn (2021). Add Bonello’s film to that list, though even more than other examples in this genre, its specificity and execution feel entrenched in a past many viewers want to forget.

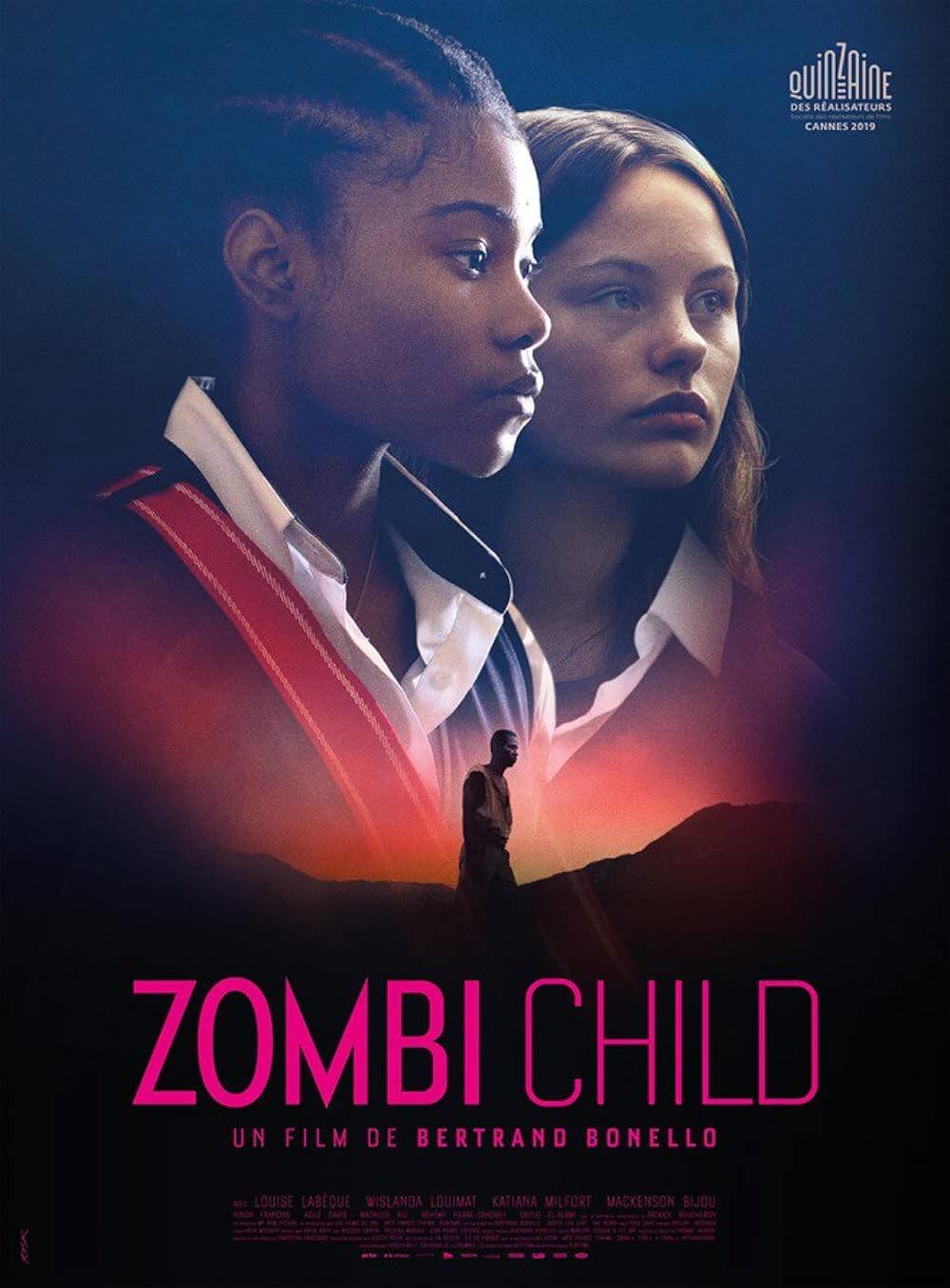

Much of the film centers on an unnamed teen, played in a terrific performance by Louise Labèque from Bonello’s Zombi Child (2019). It’s safe to assume that Bonello based the character on his daughter, so let’s call her Anna. But it’s also worth considering how much the character reflects the director, spinning his wheels in quarantine and desperate to busy himself with a new project. Regardless, Anna spends her time in her room, alternately glued to screens and lost in her imagination. Much of her attention involves the YouTube channel of Patricia Coma (Julia Faure). This self-proclaimed lifestyle guru promises to help her viewers with tips on healthy living, product recommendations, and defeatist weather updates (“You can’t go out anyway, so never mind,” she resolves). Patricia goes from teaching her viewers German to instructing them how to access limbo through their subconscious. She also sells the Revelator, a handheld version of the Milton Bradley game Simon, where the player attempts to replicate the increasingly complex pattern of tones and colors on the device. It might also prove you have no self-control over your choices and expose the illusion of free will. Hence, Anna can do it blindfolded.

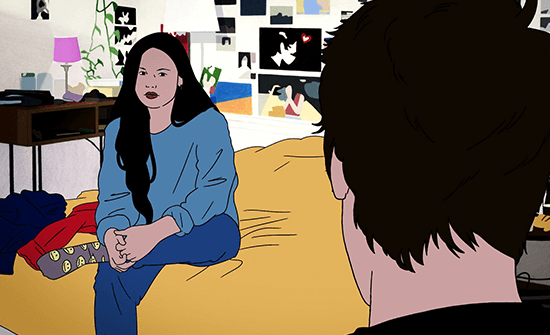

But these are among the more coherent ideas in Coma, which unfolds with the gradual degradation and breakdown of the protagonist’s mind. Though quiet moments where she dances alone in her room seem almost peaceful, she also plays five-finger fillet in the kitchen, going so far as to tape down her hand to prevent herself from recoiling. Her Barbie and Ken dolls become avatars for people in her life, including her boyfriend Scott, voiced by Gaspard Ulliel (who died in a skiing accident while Bonello was finishing post-production). Rendered with stop-motion animation—echoing Todd Haynes’ technique in Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (1987)—the dolls act out jealous relationship scenes punctuated by the laughter of a live studio audience. The dolls perform incestuous sex acts and read abhorrent Tweets written by Donald Trump. These segments gradually overlap and blend with others formally, such as archival footage of Deleuze talking about the danger of dreams. The aspect ratios shift from anamorphic widescreen for Coma’s videos to the Academy ratio for Anna’s scenes, though not consistently. Similarly, the video sources change, sometimes on a whim, including crisp photography, grainy camcorder, a flat animation style, and surveillance footage monitored by an unknown security force.

But these are among the more coherent ideas in Coma, which unfolds with the gradual degradation and breakdown of the protagonist’s mind. Though quiet moments where she dances alone in her room seem almost peaceful, she also plays five-finger fillet in the kitchen, going so far as to tape down her hand to prevent herself from recoiling. Her Barbie and Ken dolls become avatars for people in her life, including her boyfriend Scott, voiced by Gaspard Ulliel (who died in a skiing accident while Bonello was finishing post-production). Rendered with stop-motion animation—echoing Todd Haynes’ technique in Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (1987)—the dolls act out jealous relationship scenes punctuated by the laughter of a live studio audience. The dolls perform incestuous sex acts and read abhorrent Tweets written by Donald Trump. These segments gradually overlap and blend with others formally, such as archival footage of Deleuze talking about the danger of dreams. The aspect ratios shift from anamorphic widescreen for Coma’s videos to the Academy ratio for Anna’s scenes, though not consistently. Similarly, the video sources change, sometimes on a whim, including crisp photography, grainy camcorder, a flat animation style, and surveillance footage monitored by an unknown security force.

Much of Coma proves unsettling and jarringly erratic, reminiscent of David Lynch’s low-fi digital video work on his experimental nightmare, Inland Empire (2006). This is especially true during Anna’s POV nightmares in the woods, where she’s pursued by figures with creepy, lifelike masks and surrounded by disembodied screams. But Anna’s thematic preoccupations—or perhaps they’re Bonello’s—prove equally disturbing regardless of how the film conveys them in aesthetic terms. Take the Zoom call between Anna and her friends, where they discuss their favorite serial killers, until a real killer invades the scene. Did that really just happen? Everyone went to some dark places when quarantined, and Anna is no exception. Still, Bonello uses moments like this to comment on our desperate need to connect. In the video conference’s gallery view, she appears to be part of something. But Bonello also pulls back to show that Anna is alone in her room on the call, revealing that there’s no real connection. It’s a somewhat less narratively cohesive version of Jane Schoenbrun’s We’re All Going to the World’s Fair (2021), capturing how screens and various media replace our reality with a convincing but unreal illusion.

Besides directing, writing, and producing the film, Bonello, who worked in music before becoming a filmmaker, also provides an excellent hypnotic score that imbues this project with a hallucinatory quality. If Coma isn’t always clear from one moment to the next, it captures a relatable feeling from a specific time and place, even if that place exists in someone’s head. Watching the film can feel disorienting, slow, and aimless, but it’s not without a moving desire to empathize with his protagonist, exploring her mental state across a fluid understanding of time (the film might take place over a couple of days or an entire year). The filmmaker even ends Coma with a touch of sentiment—a montage of natural disasters, violent storms, volcanoes erupting, and glaciers collapsing, yet also a verbal reassurance to his daughter that, from such destructive episodes, “There’s always a rebirth.” The director’s tender words to his daughter underscore this with the etymology of the word limbo, which dates back to the Medieval Latin word limbus, meaning border or margin—a space that Bonello observes is waiting to be filled, representing a hopeful opportunity for something new. Coma acknowledges that life comes with highs and lows, life and death, an equilibrium in the universe as natural as spring following winter. Though it’s Bonello’s least accessible film to date, it also might be his most personal.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on May 9, 2024.)

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review