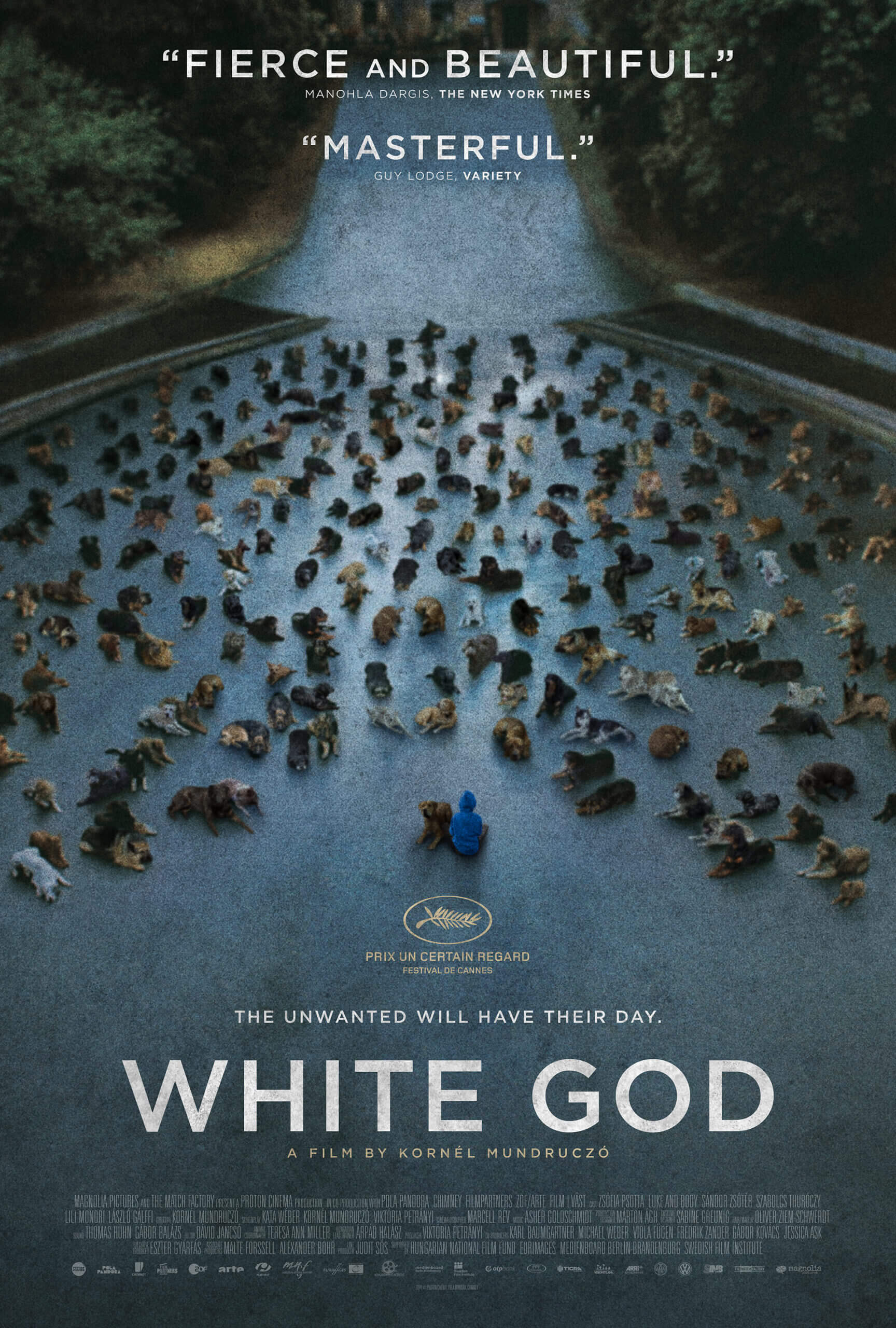

Blue Ruin

By Brian Eggert |

Dark and devoid of excess plot, Blue Ruin tells a revenge tale filled with superbly tuned suspense and clean, efficient filmmaking. Jeremy Saulnier serves as writer, director, and cinematographer for this independent thriller, which also presents a kind of self-aware art piece about its subject. Backwoods thrillers of this ilk are frequent (the recent Out of the Furnace comes to mind), where one party ruthlessly pursues another out of some stubborn sense of justice or profit until things become so unruly that neither party remembers what started the conflict in the first place. These stories are usually accompanied by gorgeous visuals of the wasted, rough terrain their characters inhabit, the prevailing presence of firearms, and a warped sense of morality attached to every action. Expect no less here, except with a captivatingly spare quality to the presentation. By the end, Saulnier seems to be saying there’s no eye-for-an-eye justice in such Southern-fried communities; everyone just keeps gouging eyeballs until they’re blind.

The title refers to the rusty, bullet-hole-ridden blue Pontiac that rests beachside in Delaware when the film opens. This jalopy is the home of the maladroit Dwight (Macon Blair, also executive producer), a thirtysomething bum with a scruffy beard, greasy hair, and gentle, melancholy eyes. Dwight spends his days scrounging through dumpsters for food and collecting bottles from the beach. Occasionally he sneaks into someone’s house for a bath or catches a fish for a meal, and at night he reads. One day, a cop comes knocking on his Pontiac’s window to inform him that Wade Cleland, a man imprisoned for murder since 1993, will soon be released. This incites Dwight into action, first bringing his broken-down car to working order by reconnecting the battery and putting air in the tires, then by heading out to Virginia, where the murderer will be released.

Saulnier is careful about how he releases information about Dwight, his situation, and his impetus throughout the film. Dialogue is minimal, if almost completely unnecessary for the film’s first half. Dwight quickly finds Wade, and we soon discover the ex-con was responsible for killing Dwight’s parents. But as much as Dwight seems to have spent ages planning out how he would exact retribution, he’s no professional killer and unavoidably makes mistakes along the way, which further complicate matters. After stabbing the former jailbird to death, Dwight, covered in blood and having to steal the Clelands’ car because he dropped his own car keys, barely escapes his victim’s gun-crazed family. Dwight cleans himself up and, now clean-shaven and donning a casual businessman getup, visits his sister Sam (Amy Hargreaves), whom he tells to get out of town, as the Clelands will undoubtedly retaliate.

A grim comic realism inhabits Blue Ruin as Dwight engages the Clelands. Though self-sufficient for years and rather resourceful as a tramp, Dwight’s stubborn self-reliance gets the better of him on several occasions. At one point, he’s shot in the leg with an arrow and tries to perform surgery on himself to remove it; the squirm-inducing, ineffectual results land him in the hospital. He’s also completely inexperienced with guns and doesn’t (like protagonists often do in such revenge-based material) become an instant gun aficionado. He even receives a crash course in weaponry from former high school buddy Ben (Devin Ratray, best known as Buzz in the first two Home Alone movies), but his performance in the final, bloody standoff could hardly be called that of a gun enthusiast. Throughout the film, Dwight’s aversion toward guns yet his need to use them results in a shy subtext about Americans (specifically the South) being over-armed and in desperate need of gun control.

Though barely developed as a three-dimensional character, Dwight remains fascinating in part because of Blair’s everyman appearance after he sheds his vagabond shell. Our imaginations, propelled by the look of ache in Blair’s eyes, fill in the blanks as to the emotional devastation he’s suffered. Blue Ruin is like that, deepening itself through poignant images over exposition, resourceful filmmaking over the need for new scenarios, and moving at such a calculated pace through such to-the-point images that not a single shot feels superfluous. Saulnier’s capable lensing makes expert use of the widescreen frame, and the music by Brooke and Will Blair creates a sense of dread under the proceedings. Debuting at Cannes in 2013, Blue Ruin has won several top prizes in minor festivals since, but the film hasn’t broken through in its wider distribution in 2014. Viewers with an affinity for severe, escalating tensions in a Southern backdrop, a curiously ever-growing subgenre, will nonetheless find a film driven by a more exacting vision than others of its kind.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review