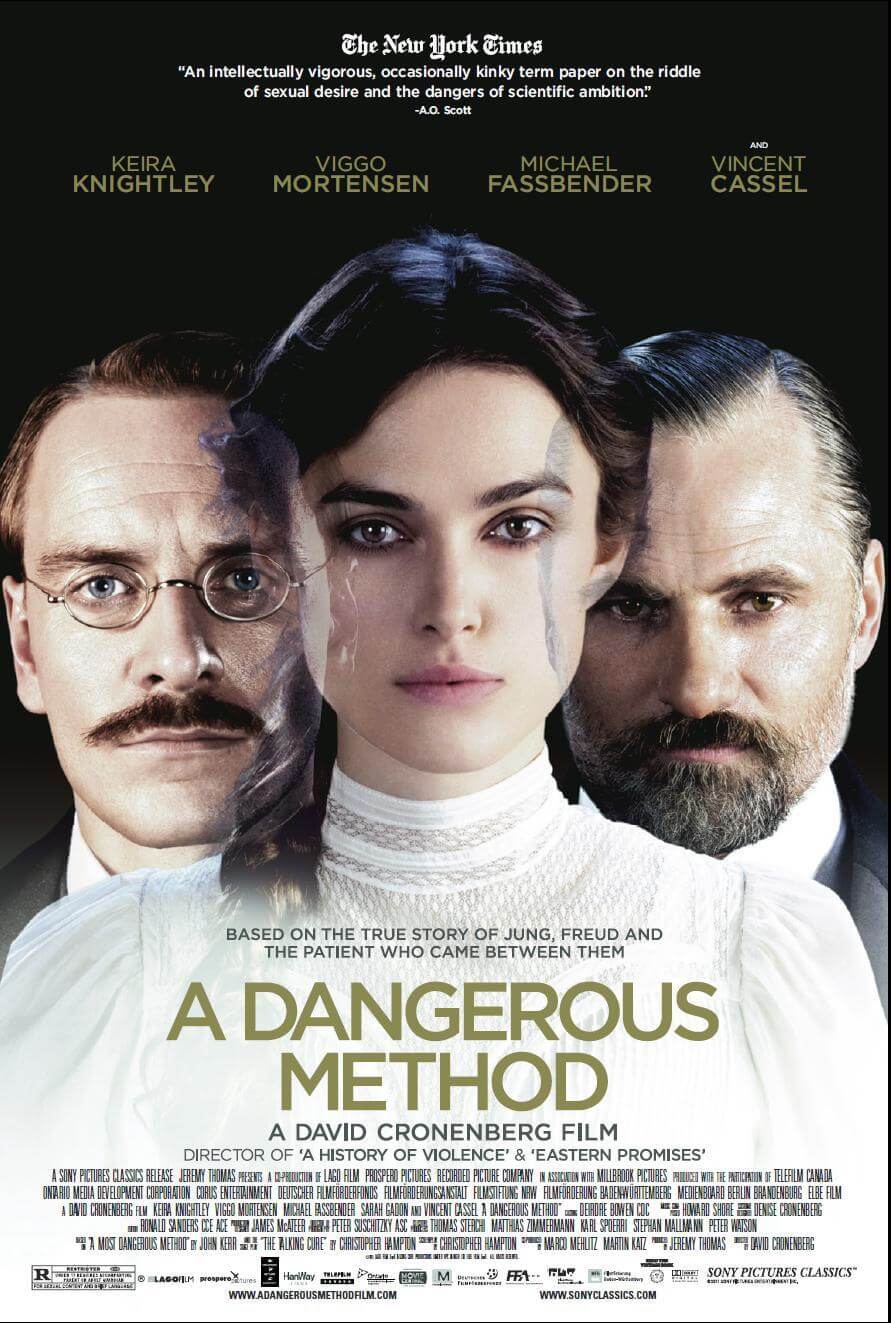

A Dangerous Method

By Brian Eggert |

A Dangerous Method delves into familiar ideas for the cinema of its director, David Cronenberg. Adapted by Christopher Hampton from his play, the film investigates the adolescent years of psychoanalysis, and therein notions of disconnection between the mind and the body, between intellect and sexual desire—two forces that psychoanalysis attempts to bring together through a sense of understanding. But to what end? The method’s father, Sigmund Freud, would argue that simply identifying the problem is enough; Carl Jung would rather provide a solution for his subjects, an alternative way of living to triumph over their problem. Such themes resound throughout Cronenberg’s oeuvre and inform his most complex works, but none so directly as this. But do not let its directness deceive you. Though shot with meticulous precision and fuelled by compelling dialogue, the film appears to be a straightforward costume drama, dare I say even Oscar bait. And yet, Cronenberg’s film is a richly complicated tale that finds pioneers lost in their own frontier.

In Europe at the dawn of the last century, a personal and professional love triangle develops between Jung (Michael Fassbender), Freud (Viggo Mortensen), and the disturbed patient who brought them together. We first see the Russian patient Sabina Spielrein (Keira Knightley) in 1904 as she arrives at the Burghölzli Clinic in Zurich; she screams and wails and cackles, her body contorting as hospital staff carry her inside. Under Jung, she will be his subject of “psychoanalysis”—the breakthrough Freudian process known as “the talking cure”. Although Jung and Freud have never met in person or yet exchanged letters, Jung respects Freud immensely, and using his technique, Jung is able to calm Spielrein’s episodes. Well-educated and highly intuitive, Spielrein approaches her issues—stemming from a link between sexual desire and the humiliating abuse she received from her father beginning at the age of four—with a level of understanding unique in patients like her. When she voices her desire to become a doctor, she begins to assist with Jung’s work.

When Jung and Freud eventually meet, they talk for hours and share ideas between them unique in their field, but their professional dichotomy also becomes apparent. Freud insists that their area of study should be limited to a strict practice of analyzing patients through exclusively sexual terms, to prevent their arguments from being torn apart by critics looking for holes in their theories; whereas Jung bears an open mind toward other, more out-there explanations ranging from telepathy to precognition—everything, Jung claims, happens for a reason. Despite their differences, Jung considers their professional involvement a friendship, whereas Freud, quick to correct Jung that their practice should be called “psychoanalysis” because it’s more “logical” and simply because “it sounds better”, never resists underlining his authority over his younger colleague. Jung’s wealth and his status as a welcomed Catholic in Freud’s pointedly Jewish-dominated turf rouse Freud’s resentment, to which Jung remains oblivious upon their first meetings.

Indeed, there is much that Jung does not see, and much that influences him. In one scene, Spielrein and Jung use his upper-class wife, Emma (Sarah Gadon), to test the effectiveness of word association tests. Spielrein points out that, based on her responses, Jung’s wife may have doubts about their marriage, a notion he was oblivious to until Spielrein identified it. Later, when Freud sends him a patient, fellow analyst and bohemian Otto Gross (Vincent Cassel, intense in spite of his brief time onscreen), Jung is quickly taken by Gross’ theory that nothing should be repressed, that we should embrace our natural desires without hesitation. As a result, Gross sleeps with his patients and suggests Jung do the same with Spielrein. Although resistant at first, Jung remains open to the question of why people suppress their most basic desires and ultimately concedes to Spielrein’s forward pleas that he provide her with sexual experience to better understand her chosen field. However, their affair has greater implications not only for Jung and Spielrein but also for Freud, who defends his branch of psychological theory with equal parts passion and paranoia.

Indeed, there is much that Jung does not see, and much that influences him. In one scene, Spielrein and Jung use his upper-class wife, Emma (Sarah Gadon), to test the effectiveness of word association tests. Spielrein points out that, based on her responses, Jung’s wife may have doubts about their marriage, a notion he was oblivious to until Spielrein identified it. Later, when Freud sends him a patient, fellow analyst and bohemian Otto Gross (Vincent Cassel, intense in spite of his brief time onscreen), Jung is quickly taken by Gross’ theory that nothing should be repressed, that we should embrace our natural desires without hesitation. As a result, Gross sleeps with his patients and suggests Jung do the same with Spielrein. Although resistant at first, Jung remains open to the question of why people suppress their most basic desires and ultimately concedes to Spielrein’s forward pleas that he provide her with sexual experience to better understand her chosen field. However, their affair has greater implications not only for Jung and Spielrein but also for Freud, who defends his branch of psychological theory with equal parts passion and paranoia.

The story itself remains as close to fact as possible, using many of the actual letters between this trio to push the story forward, while an almost intervallic structure that jumps several years at a time never feels episodic or unconnected. Each of the three main characters has a defined arc, but beyond that, as characters, they curiously represent their fields. Freud’s sexual repression, guided by his not irrational suspicion that as a Jew all eyes are watching, brings about his theory that every symptom has a sexual foundation. Jung’s prim and proper exterior gives way to a figure that must search in every direction, reaching for answers anywhere he can find them, but without devotion to a singular idea. Finally, Spielrein believes that in order to truly embrace one’s sexuality, one must destroy their individuality and commit to becoming a new individual with their partner; in turn, the sexual act becomes one of destruction and creation at once: a decidedly novel thought and an appropriate one in Cronenbergian logic.

At first, this costume drama may seem to be unlikely material for the one-time helmer of “venereal horror” such as The Brood and Videodrome; however, much like the majority of Cronenberg’s work, this is an intellectual motion picture that considers our most human, bodily nature in a very cerebral way, but without reducing the story to clinical emotions and detached characters. If it must be compared with other Cronenberg films, A Dangerous Method has the most in common with Dead Ringers, his sordid drama about identical twin gynecologists played by Jeremy Irons, as both concern the dual nature of humanity and finding—or not—a balance between two Selves in one body. In another way, the film has much in common with The Fly, another love triangle, with both being about a scientist on the cusp of a breakthrough, only to thwart his own efforts through his personal desires and professional inflexibility. Unlike Jeff Goldblum’s Brundle, Jung doesn’t become an actual monster, but he does lose himself for a considerable period of time, and like Brundle, regrets his behavior after his lesson is learned: “Sometimes you have to do something unforgivable to go on living.”

Approaching 70 years of age, Cronenberg has matured his technique from his early career schlock to the seasoned, refined style usually associated with the earlier, more economic works of Stanley Kubrick (Paths of Glory comes to mind). Every shot is efficiently composed with a minimum of cinematic ornamentation, his technique informed by the setting, crisp and clean, and classical. His compositions employ several split-diopter shots, showing the patient in the foreground and the analyst in the background, both in focus. Cronenberg’s longtime crew is in attendance: cinematographer Peter Suschitzky captures Vienna’s formality and beauty; Cronenberg’s longtime composer Howard Shore allows dialogue to stimulate most scenes, but utilizes a dramatically Germanic score to increase the growing sense of destruction between the lead characters; editor Ronald Sanders trims the fat for leaner storytelling, as this 99-minute feature presses on with an urgency that makes every scene so necessary to the proceedings, deepening every character within Hampton’s complicated narrative.

Cronenberg’s most apparent and important collaborators are his actors; this is an actor’s film, driven by three incredible performances, foremost Knightley’s. As Spielrein, she contorts her body and renders expressions that she and Cronenberg derived from actual descriptions of “hysterical” females from the period; in her episodes, there seems to be a demon pushing and pulling from inside of her, forcing her jaw outward and her hips back. Later, when her character has graduated into a psychoanalyst herself, she is composed, but there’s clearly something of her former Self behind those eyes. We see it in a later scene with Jung, who Fassbender renders with civilized airs, but also a degree of mysticism—which emerges in his fascinating, haunting moments of precognition, particularly when he foresees WWII in a dream in which Lake Geneva is filled with blood and corpses. Fassbender carries his scenes through Jung’s barely realized desire to break free of his ordered lifestyle. Both Jung and Freud admit their families have held back their progress in their careers, and both remain fastidiously committed to their respective familial institutions, affair notwithstanding. Mortensen has the greatest challenge in depicting Freud, that beleaguered icon, into a human character whose vanity and sly posturing make him compelling. In his third collaboration with Cronenberg (after A History of Violence and Eastern Promises), Mortensen brings much humor and vulnerability to an otherwise antiseptic figure.

The impeccably acted film ends with a postscript coldly detailing the fates of these characters, how Freud died of lung cancer, Spielrein was rounded up by the Nazis and shot in WWII, and Jung passed on of old age. A Dangerous Method is not a sentimental film of sympathetic and compassionate characters, as you might expect from a typical Oscar season period piece. Instead, the film is a decidedly (and surprisingly) Cronenbergian work filled with perceptive characters and a compelling narrative, at times as wild as Spielrein, yet at others as reserved and reasoned as Freud, but like Jung always searching, and without need for metaphoric violence or bodily grotesqueries to communicate its purpose. Cerebral though it may be, it does not lack emotion, just links its emotional underpinnings with lofty historical and scientific discussions. Even still, in the way Hampton entwines psychoanalytic theories into the characters themselves, viewers need not be familiar with Freudian hypotheses to appreciate the film’s complexity. But it is that complexity, and the intricate merging of character and method, that makes this film an abundantly rewarding experience on both emotional and intellectual planes, and another example of why Cronenberg’s continued growth and diversity places him among our best filmmakers.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review