The Brood

By Brian Eggert |

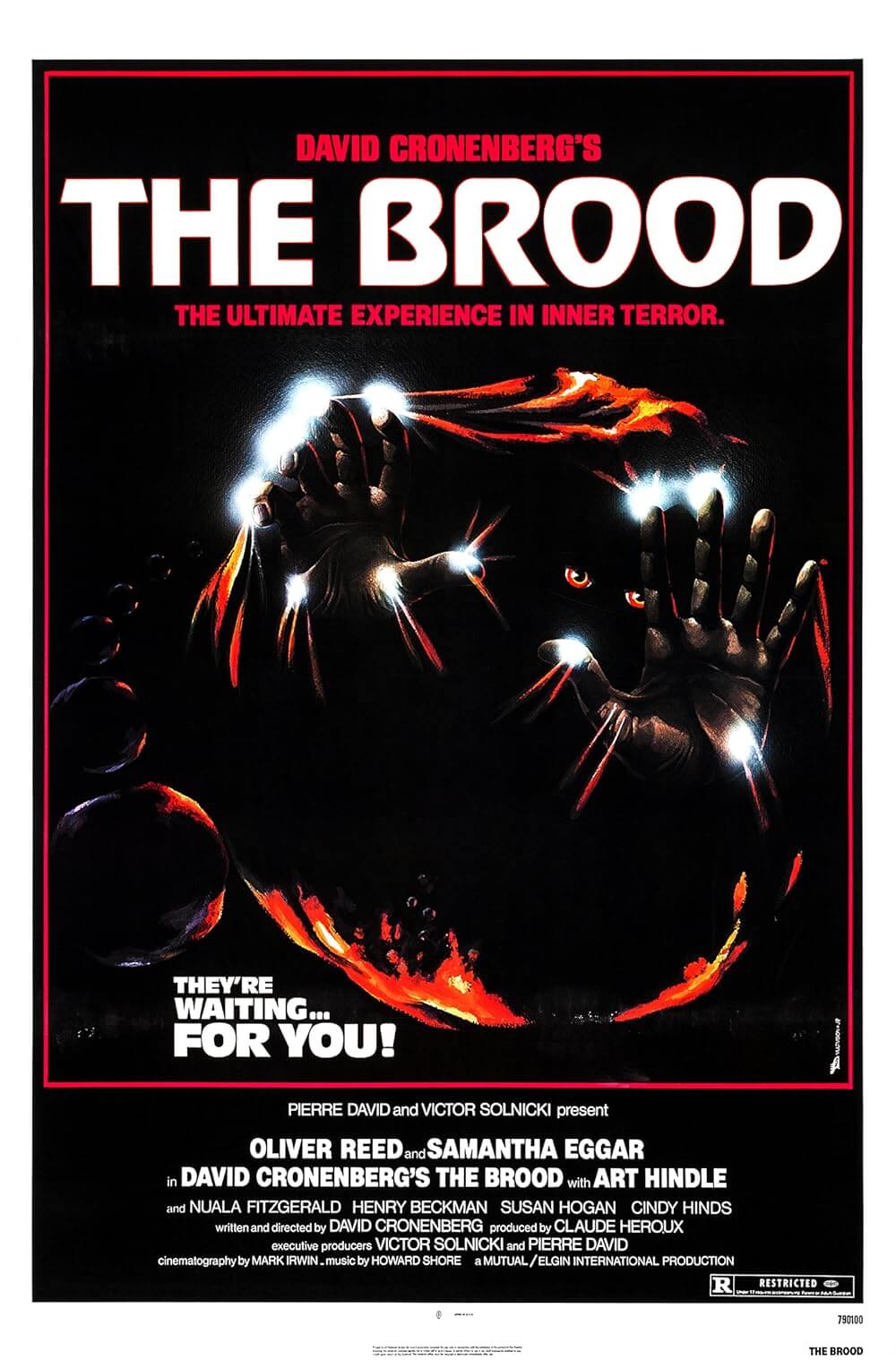

The Brood has been called David Cronenberg’s “family” picture. Those who have seen the film can attest to the irony of this label. Expressing himself in symbolic terms, the Canadian director draws from his own life to turn filmmaking into an exercise of deeply personal artistic therapy. His film would later become the first example of a characteristically ‘Cronenbergesque’ work, in the most mature, emotionally relevant sense. Misunderstood upon its release, the film transcends basic horror aims and harbors repulsive imagery as a potent visualization of internalized emotions. Those feelings come spilling out into the screen with an effective dramatic veracity that, for the first time in Cronenberg’s career, expresses the director’s auteurist obsession to define the connections and separations between the mind and body in more philosophical terms than mere horror. Made during the tax-shelter days of Canada’s film industry, The Brood was Cronenberg’s fourth feature, but his first attempt at serious-minded filmmaking. Believing catharsis to be “the basis of all art,” his story’s foundation came from his own marital troubles and the resultant emotional trauma that ensued, making it his most autobiographical work. Of course, the translation from life to art was not a literal one.

The story comes oozing with Cronenberg’s signature bodily horror, with the suggestion that strong emotions cause a physical response. Anger, fear, and doubt—they leave their mark on the body. Extending that concept to horrific extremes, psychosomatics take living, breathing form in the film, resulting in a macabre take on a melodramatic subject. Cronenberg’s institution of institutions (from Starliner Towers in Shivers to Antenna Research in eXistenZ) continues with psychotherapist Dr. Hal Raglan (Oliver Reed), whose “Soma free” clinic offers emotional healing through his exclusive new treatment, called psychoplasmics, which is also the subject of his book, “The Shape of Rage”. Raglan seeks to externalize repressed inner feelings with the understanding that every emotion has a physical counterpart; for example, when extreme stress causes a headache or ulcer. Raglan’s therapy causes more severe results, however. One patient in the opening scene forms welts and sores about his body as he confronts his daddy issues. Raglan’s top patient is Nola Carveth (Samantha Eggar), a disturbed woman filled with rage—chaotic and complicated feelings toward her husband, Frank (Art Hindle).

Their young daughter, Candice (Cindy Hinds), gets caught in the middle when Frank refuses to allow Nola to see her after an incident at Raglan’s institute. Someone, presumably Nola, has bitten and bruised the girl. Further incidents prove that the culprit is not Candice’s mother, but rather mutated children asexually birthed from her. Hideous, reactionary creatures recalling something like the murderous dwarf in Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now, the eponymous Brood serve as vessels to their mother’s unconscious emotions. When Nola resents or feels hatred toward someone, her Brood act out her unconscious desire to harm them. Raglan knows of their existence and keeps this secret locked away, along with their mother. Frank soon discovers the horrible truth, and to protect Candice, his confrontation with Nola requires that he kill her, lest her psychoplasmic children act out some resentment toward his daughter.

Their young daughter, Candice (Cindy Hinds), gets caught in the middle when Frank refuses to allow Nola to see her after an incident at Raglan’s institute. Someone, presumably Nola, has bitten and bruised the girl. Further incidents prove that the culprit is not Candice’s mother, but rather mutated children asexually birthed from her. Hideous, reactionary creatures recalling something like the murderous dwarf in Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now, the eponymous Brood serve as vessels to their mother’s unconscious emotions. When Nola resents or feels hatred toward someone, her Brood act out her unconscious desire to harm them. Raglan knows of their existence and keeps this secret locked away, along with their mother. Frank soon discovers the horrible truth, and to protect Candice, his confrontation with Nola requires that he kill her, lest her psychoplasmic children act out some resentment toward his daughter.

While fighting with his ex-wife for the custody of his daughter Cassandra, Cronenberg conceived the film’s scenario. He had since remarried, sharing custody of the child with his ex, whom he considered unstable. She announced plans to relocate with the child from their Canadian home to California, where she planned to live with some “nice people”. Cronenberg refused to let this happen and removed his daughter from school the same day, later filing a court order that prevented his ex from leaving with the child as planned. Enraged, his ex left on her own and never returned. When charged with writing a new script to follow Rabid, his profitable exploitation of venereal horror from 1977, the result was not what he had planned. Victor Solnicki and Dick Schouten, producers from Vision 4, and executive producer Pierre David, assigned Cronenberg to write “The Sensitives”, an idea that would eventually become Cronenberg’s head-exploding Scanners. But when he sat down at his typewriter, it was as though The Brood’s eventual tagline “the ultimate experience of inner terror” came pouring out.

Instead of completing the proposed script about a war involving psychics, Cronenberg turned in The Brood. During the tax-shelter days, Canadian financiers were desperate for material—any material—so it mattered not that Cronenberg didn’t complete the scenario he originally promised. That a script was finished at all meant the film could begin shooting and the investors would earn their desired tax breaks. Working with his highest budget yet, Cronenberg was given $1.5 million to complete the project, affording him the ability to hire quality actors, which he had never been able to do before. Oliver Reed and Samantha Eggar joined the cast, the latter calling the experience the strangest of her career. Elevating Cronenberg’s status from his schlocky B-movie origins with Shivers and Rabid, and bearing nothing in common with his racecar movie Fast Company from earlier in 1979, The Brood emerged from the director’s impassioned desire for artistic expression. He was no longer making a movie just out of curiosity, to test himself, or to get a reaction, which is how he approached Shivers and Rabid. Rather, he sought to capture substantial emotions through horror imagery, expanding the range of horror from ‘low culture’ to a desired ‘high culture’ ideal.

Instead of completing the proposed script about a war involving psychics, Cronenberg turned in The Brood. During the tax-shelter days, Canadian financiers were desperate for material—any material—so it mattered not that Cronenberg didn’t complete the scenario he originally promised. That a script was finished at all meant the film could begin shooting and the investors would earn their desired tax breaks. Working with his highest budget yet, Cronenberg was given $1.5 million to complete the project, affording him the ability to hire quality actors, which he had never been able to do before. Oliver Reed and Samantha Eggar joined the cast, the latter calling the experience the strangest of her career. Elevating Cronenberg’s status from his schlocky B-movie origins with Shivers and Rabid, and bearing nothing in common with his racecar movie Fast Company from earlier in 1979, The Brood emerged from the director’s impassioned desire for artistic expression. He was no longer making a movie just out of curiosity, to test himself, or to get a reaction, which is how he approached Shivers and Rabid. Rather, he sought to capture substantial emotions through horror imagery, expanding the range of horror from ‘low culture’ to a desired ‘high culture’ ideal.

For realistic dialogue, he took lines almost verbatim from actual arguments with his ex-wife. He would later admit that the familial conflicts of the story could be considered standard melodrama, what he calls a “disease-of-the-week” story, but his weighty approach to such gory imagery proves unique in horror of the period. The grotesque visuals in the film reach their peak in the climax when Frank confronts Nola. Up to this point, the viewer has only seen small sores, a large lymphatic tumor, and mutated children—all rather tame for Cronenberg, considering the vast effects-driven experimentation that came in his earlier work (bubbling stomachs, phallic armpit parasites, etc.). Eggar plays her entire role seated or on her back, seemingly implanted onto the ground like a pregnant animal. When she opens her garb to Frank in the finale, she reveals large boils, but also a birth sack emanating from her belly, reminiscent of the placental casing that emerges from many mammals during labor. Nola bites the sack open with her teen and bloody fluid pours out; she tears the sheath away and unveils her psychoplasmic child. Licking the thing clean like an animal mother, the image is both unsettling yet inspired by Cronenberg’s logical-if-malformed biology. The sight is at once monstrous and bizarrely natural. Censors required Cronenberg cut the scene for its graphic nature, despite the fact that the image is not one of violence or depravity, simply warped motherhood.

As equally compelling and nauseating as the imagery may be, Cronenberg’s low budget cannot help but shape the film’s reception today as a transitional work between his early B-movies and his later, more serious films. Though his philosophical approach to horror had never been more confident, he had yet to fully escape his schlock origins. The small budget gave him Reed and Eggar, but no actor could elevate the shoddy appearance of the Brood children. In the wrong company, their appearance in snowsuits or blood-soaked pajamas might induce unintended laughter. Or consider the music. Composer Howard Shore wrote his first of many scores for Cronenberg on The Brood, evoking strings pulled from Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho that match the pangs of violence onscreen; only, instead of Norman Bates’ knife, the strings align with a meat tenderizer or wooden block hammer beating. Years later, Shore’s music would become a key indicator of the severity behind Cronenberg’s work, but here it has the opposite effect. Moreover, Roger Corman’s New World Pictures distributed the film; an association with Corman alone immediately labeled the movie as something not critically relevant in any artistic way.

As equally compelling and nauseating as the imagery may be, Cronenberg’s low budget cannot help but shape the film’s reception today as a transitional work between his early B-movies and his later, more serious films. Though his philosophical approach to horror had never been more confident, he had yet to fully escape his schlock origins. The small budget gave him Reed and Eggar, but no actor could elevate the shoddy appearance of the Brood children. In the wrong company, their appearance in snowsuits or blood-soaked pajamas might induce unintended laughter. Or consider the music. Composer Howard Shore wrote his first of many scores for Cronenberg on The Brood, evoking strings pulled from Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho that match the pangs of violence onscreen; only, instead of Norman Bates’ knife, the strings align with a meat tenderizer or wooden block hammer beating. Years later, Shore’s music would become a key indicator of the severity behind Cronenberg’s work, but here it has the opposite effect. Moreover, Roger Corman’s New World Pictures distributed the film; an association with Corman alone immediately labeled the movie as something not critically relevant in any artistic way.

Both Cronenberg and Shore would grow in incredible strides over their next two films together. Cronenberg’s intention was to advance horror into a thoughtful marriage of confrontational imagery and mind-body philosophizing, but it would take getting through Scanners before he could become the unclassifiable filmmaker he is today, an objective he achieved with Videodrome in 1982. Upon first seeing The Brood, the film is unquestionably disturbing. After reconsideration of its autobiographical origins, it becomes moving in a strange, horrific way. Given the themes of the film, as they relate to its director, every awful moment has a deep-rooted emotional counterpart, which supplies a distinctive response infinitely more complex than a standard horror movie could provide. The picture is Cronenberg’s most satisfyingly melodramatic work, fully realized for emotional consequences over typical horror revulsion, and a crucial stepping stone in the advancement of one of today’s most important filmmakers.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review