The Definitives

Millennium Mambo

Essay by Brian Eggert |

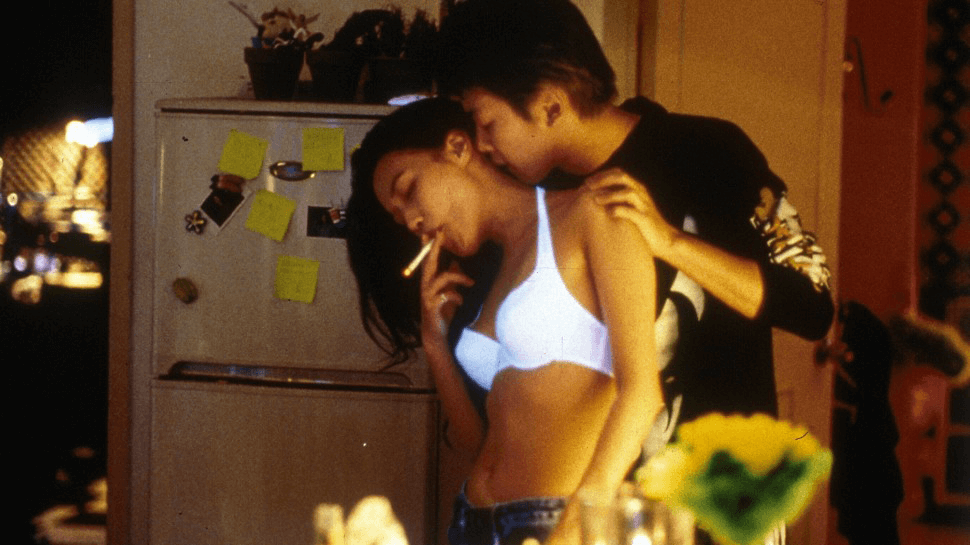

The transfixing first shot of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Millennium Mambo finds Vicky, played by Hou regular Shu Qi, walking down an enclosed pedestrian corridor in mesmeric slow motion. Above, fluorescent lights glow, giving the passage an unearthly blue radiance. Under the image of Vicky walking, her hair bouncing with each breezy step, an electronic score eases into the aural space, adding a thumping and propulsive tempo. Vicky looks back and through the openings along the tunnel, smoking her cigarette and smiling as if beckoning the camera to follow. Though she appears in hypnotic bliss, her remote and melancholic voiceover recollects her past with a certain distance that only comes with time. Vicky refers to herself as “she,” as though she was another person then, in 2001. She narrates from ten years later. The shot, which lasts two-and-a-half unbroken minutes before the title screen, establishes Hou’s central theme in literal and figurative terms. Millennium Mambo is about reflecting on a stagnant, transitional period of youthful celebration at the arrival of the twenty-first century—lost in neon-glimmering parties, bad relationships, thankless jobs, and aimless searching. For Vicky, telling the story about this chapter of her life is more for herself than the viewer. Searching her memories, she uncovers the texture of an era.

Renowned for his humanism and sophisticated use of poetic form, Hou remains one of the most prominent, awarded, and influential figures in global cinema and arguably the preeminent voice in Taiwanese cinema. Born in 1947 in China’s Guangdong province, Hou’s family moved to Taiwan shortly after his birth. By the time he graduated high school, both of his parents had died, and after his mandatory military service, he studied film at the National Taiwan Arts Academy. Once he began writing and directing films in Taiwan in the 1980s, he quickly established a reputation for telling autobiographical stories, often about life in southern Taiwan, far removed from the capital of Taipei, which remain his most celebrated. His films, along with others by Edward Yang and Tsai Ming-liang, signaled a shift in the national cinema—one supported by Hou’s encouragement of local filmmakers and productions—to explore Taiwanese history and identity. Although his career has spanned over forty years, few of his films have received distribution in the US outside of the festival circuit. However inadequate his notoriety may be stateside, in arthouse and global film circles, he maintains a reputation for expanding the medium’s horizons with his patiently long takes, reliance on non-actors for natural performances, and ponderous approach to narrative.

Millennium Mambo is not Hou’s most acclaimed work, but it’s unique in its remarks on the here and now of Taiwan in 2001. By contrast, many of Hou’s earlier films deal with historical matters related to Taiwan’s history. With that in mind, perhaps a high-level overview of the country’s recent history will better place the film in its context. Although Taiwan was self-governing before the 1600s, the island became a European colony in the seventeenth century, followed by a two-century Chinese rule. After the first Sino-Japanese War in the 1890s, Taiwan became a Japanese colony. And after World War II, the allied powers granted control of the island to China’s Nationalist party, the Kuomintang (KMT), then fighting in a civil war over controlling interests of the mainland. But on February 28, 1947, anger over the arrest of a woman for illegally selling cigarettes launched protests against the KMT-led government, who responded by killing a high estimate of 28,000 Taiwanese before declaring martial law, starting a period known as the White Terror. Two years later, the KMT had been defeated on the mainland by what became the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and the KMT fled to Taiwan. Not until 1987 was martial law lifted, spawning a period of democratic, economic, and industrial development. In the 1990s and beyond, Taiwan sought independence from the PRC and to downgrade the power of the KMT. However, the PRC has endeavored to reclaim authority over the otherwise independent Taiwan—a claim that many countries have failed to argue out of fear of political and economic penalties from China.

Millennium Mambo is not Hou’s most acclaimed work, but it’s unique in its remarks on the here and now of Taiwan in 2001. By contrast, many of Hou’s earlier films deal with historical matters related to Taiwan’s history. With that in mind, perhaps a high-level overview of the country’s recent history will better place the film in its context. Although Taiwan was self-governing before the 1600s, the island became a European colony in the seventeenth century, followed by a two-century Chinese rule. After the first Sino-Japanese War in the 1890s, Taiwan became a Japanese colony. And after World War II, the allied powers granted control of the island to China’s Nationalist party, the Kuomintang (KMT), then fighting in a civil war over controlling interests of the mainland. But on February 28, 1947, anger over the arrest of a woman for illegally selling cigarettes launched protests against the KMT-led government, who responded by killing a high estimate of 28,000 Taiwanese before declaring martial law, starting a period known as the White Terror. Two years later, the KMT had been defeated on the mainland by what became the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and the KMT fled to Taiwan. Not until 1987 was martial law lifted, spawning a period of democratic, economic, and industrial development. In the 1990s and beyond, Taiwan sought independence from the PRC and to downgrade the power of the KMT. However, the PRC has endeavored to reclaim authority over the otherwise independent Taiwan—a claim that many countries have failed to argue out of fear of political and economic penalties from China.

New freedoms, cultural growth, and the decline of the KMT’s hold on Taiwan prompted artistic opportunities for Hou, including historical reflection and consideration of his country’s national identity. Many of Hou’s earlier films—The Time to Live and the Time to Die (1985), A City of Sadness (1989), and The Puppetmaster (1993)—deal with Taiwan’s history and revolution, featuring characters whose lives are inextricably linked to those national factors that he could not address in cinema during the White Terror. They became landmark entries in the Taiwanese New Wave, a period as formative and experimental as Italian Neorealism and the French New Wave. Moreover, the travel restrictions enforced during martial law were lifted in 1987, allowing Hou to become a presence in the international film scene. He served as executive producer on Chinese director Zhang Yimou’s Raise the Red Lantern (1991) and later made films under Japanese and French producers. By Millennium Mambo’s release, Hou was known primarily for his cinematic remarks on Taiwan through a historical lens. But it would not be Hou’s first film exploring contemporary life. For instance, he also made Daughter of the Nile (1987), about a young Taipei woman who works at Kentucky Fried Chicken, reads from a manga book, and grapples with her siblings’ criminal behaviors—all factors affecting modern youths in Taipei’s contemporary urban landscape. Goodbye South, Goodbye (1995) also explored then-modern Taipei, the criminal underworld, and politics.

Contrary to many of Hou’s earlier films, Millennium Mambo considers an era in which the individual thrives, yet the culture has stopped progressing. Rather than feeling obligated to nationalistic concerns, Vicky can afford to meander between two men, spend her evenings at the discotheque, and leave for extended periods to Japan. Hou admitted to Cinéaste that the film represented a “change in direction” in his films. He sought to move away from cataloging the past into exploring young peoples’ lives, charting the rampant changes and newfound freedoms in contemporary Taipei. While developing the film, Hou intended to include it in a series dealing with modern-day issues. However, his distributor refused to commit to the idea, and the subsequent films never materialized. Hou also sought Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung Chiu-wai to star, but they were preoccupied with Wong Kar-wai’s “endless” production of In the Mood for Love (2000). So instead, the filmmaker tapped the Taipei-born actress and model Shu Qi, who received her stardom in erotic movies for the Hong Kong market before working with renown directors such as Stanley Kwan and Andrew Lau. She would collaborate again with Hou on Three Times (2005) and The Assassin (2015), though Millennium Mambo would be her most entrancing role.

The film takes place in the year of its release, 2001, during a period of cultural complacency. But like so many other Hou films, it looks back, specifically from the then-future of 2011, structuring the story in a series of unmarked chapters. Vicky’s voiceover describes the events in each chapter before they occur onscreen, flatly explaining the significant happenings in the following passage. Then we see them unfold with the foreknowledge she has supplied about the experience. Referring to herself in the third person, she invites the viewer into her memories, which she recalls dispassionately because she has lived and since outgrown them. The experience of watching her memories unfold, then, is less about following a narrative progression than capturing the aura of a period in Vicky’s history, which has since moved beyond such chaotic meandering. We know what will happen because Vicky tells us; however, we also experience the textured moments in-between the events detailed in her voiceover. In this sense, Hou’s narrative structure is inextricable from the film’s aesthetics. “I spend a lot of time searching for a kind of form that essentially is a structure,” Hou told scholar Lee Ellickson. The structure of remembered details dictates Hou’s thematic and formal agenda for the film, perhaps more than any other contributing element.

The film takes place in the year of its release, 2001, during a period of cultural complacency. But like so many other Hou films, it looks back, specifically from the then-future of 2011, structuring the story in a series of unmarked chapters. Vicky’s voiceover describes the events in each chapter before they occur onscreen, flatly explaining the significant happenings in the following passage. Then we see them unfold with the foreknowledge she has supplied about the experience. Referring to herself in the third person, she invites the viewer into her memories, which she recalls dispassionately because she has lived and since outgrown them. The experience of watching her memories unfold, then, is less about following a narrative progression than capturing the aura of a period in Vicky’s history, which has since moved beyond such chaotic meandering. We know what will happen because Vicky tells us; however, we also experience the textured moments in-between the events detailed in her voiceover. In this sense, Hou’s narrative structure is inextricable from the film’s aesthetics. “I spend a lot of time searching for a kind of form that essentially is a structure,” Hou told scholar Lee Ellickson. The structure of remembered details dictates Hou’s thematic and formal agenda for the film, perhaps more than any other contributing element.

The structure captures the randomness and fluidity of the turn-of-the-century period Hou wanted to depict in Millennium Mambo, employing a reflective strategy that intentionally transforms Taipei’s then-present into the past. This grants the viewer perspective—a feeling of being outside of time, allowing for greater reflection through the narrative device of memory. Much of the story involves Vicky’s relationship with Hao-Hao (Tuan Chun-hao), whom she has been dating since age 16. “As if under a spell or hypnotized, she couldn’t escape,” she recalls in her voiceover. “She told herself that she had NT$500,000 in the bank. When she’d used it up, she would leave him for good.” In the meantime, Vicky is subject to Hao-Hao’s jealous paranoia. When she arrives home one night, he starts taking off her clothes, though not to initiate lovemaking, but to gain better access to smell her neck, armpits, and between her legs—sniffing for evidence of some affair. He dumps out Vicky’s purse and checks her receipts and phone calls. “Have you lost it?” she asks him. Although she pushes back at Hao-Hao’s behavior, she doesn’t protest with conviction. Rather than confront his behavior, Vicky remains distracted and numbed by turn-of-the-century parties fuelled by alcohol, smoking, Ecstacy, black lights, and electronic music.

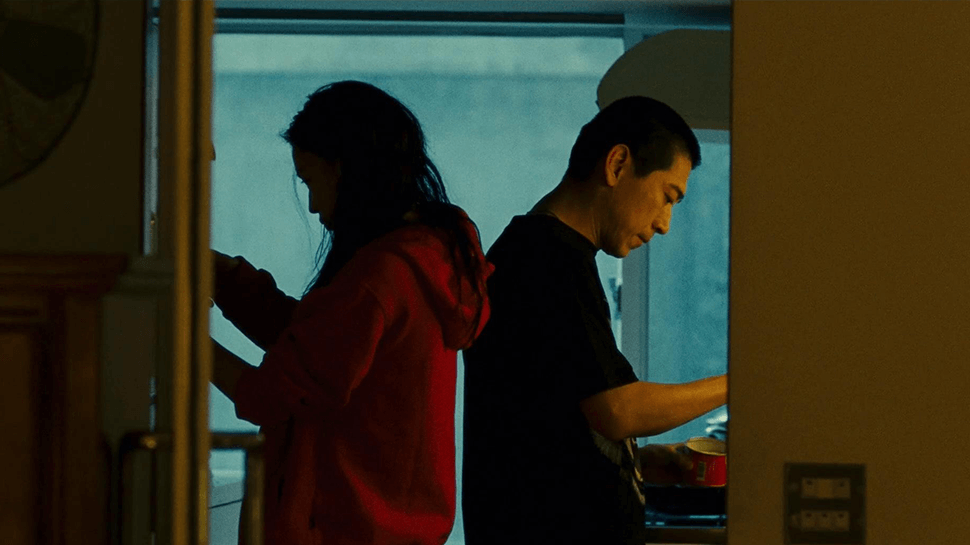

Eventually, Vicky takes a job at a hostess bar, where she meets Jack (Jack Kao), who treats her like his “closest buddy.” Jack might be Vicky’s way out of her unhealthy relationship with Hao-Hao, whose possessive, unpredictable behavior ranges from pawning his father’s stolen Rolex to starving himself to avoid military service. Her only reprieve is visiting two Japanese friends, brothers, at the wintry resort town of Yubari, located on the island of Hokkaido, to attend the Yubari International Fantastic Film Festival. There, she finds herself free of Hao-Hao and the spinning nightlife of Taipei. Upon her return, she breaks up with Hao-Hao and temporarily moves in with Jack, who’s only slightly less possessive. Restless, she finds herself discontented with Jack’s stability; he tells her not to drink alcohol and how to prepare his noodles the right way. Yet Jack has some shady deals on the side and gets into trouble with the wrong people. Soon, he disappears to Yokohama, promising to arrange for Vicky to rendezvous with him there. Lonely and living in a small apartment near train tracks, Vicky resolves to visit Japan once more, where she finds some measure of contentment under the Yubari snowfall.

The film’s ending in Japan emphasizes the elliptical nature of Hou’s filmmaking. In Yubari in the early 1990s, Hou served on the jury of the local film festival. A former mining town, Yubari’s festival was launched after the mines closed to keep their town thriving. The road that passes down Yubari’s center, where Vicky and the two Japanese boys walk, is lined with movie posters and promotional billboards and presents a veritable walk down memory lane through the history of cinema. “For me, it was a bit like a city of memories, linked to the duration of time,” said Hou in a 2001 interview with Positif. “Inserting this piece of Japan allowed me to accentuate, by contrast, the absence of memory in the youth of today, who live above all in the repetitive present, while it’s actually the accumulation of different experiences that creates memory.” Millennium Mambo, then, becomes a conversation between the past, present, and memory. The past can be clearly understood through perspective and reflection, while the present serves as a current from which we cannot escape; we can only remember it afterward.

The film’s ending in Japan emphasizes the elliptical nature of Hou’s filmmaking. In Yubari in the early 1990s, Hou served on the jury of the local film festival. A former mining town, Yubari’s festival was launched after the mines closed to keep their town thriving. The road that passes down Yubari’s center, where Vicky and the two Japanese boys walk, is lined with movie posters and promotional billboards and presents a veritable walk down memory lane through the history of cinema. “For me, it was a bit like a city of memories, linked to the duration of time,” said Hou in a 2001 interview with Positif. “Inserting this piece of Japan allowed me to accentuate, by contrast, the absence of memory in the youth of today, who live above all in the repetitive present, while it’s actually the accumulation of different experiences that creates memory.” Millennium Mambo, then, becomes a conversation between the past, present, and memory. The past can be clearly understood through perspective and reflection, while the present serves as a current from which we cannot escape; we can only remember it afterward.

For this film, as with many others, the director worked without a traditional script. Rather, the script, written by Hou’s regular collaborator Chu T’ien-wen, consists of several situations and an outline for the events that should occur. Each performer was required to improvise dialogue based on their immersion into their character. Chu, who has partnered almost exclusively with Hou since their first co-writing effort on Chen Kun-hou’s Growing Up (1983), would work with the actors alongside Hou before shooting each sequence, describing what should happen. The actors would then perform the scene, in effect shooting their rehearsals without knowing the overall story. When the film began production, Chu had only finished outlining a third of the situations. It wasn’t until halfway through production that the script, if one can call it that, was completed. The approach has been described as documentary-like, given Hou’s use of long takes and grounded situations that capture a slice of contemporary Taipei. Except, the closer one looks at Hou’s formal techniques in Millennium Mambo, the clearer it becomes that the filmmaker has more than just observation on his mind.

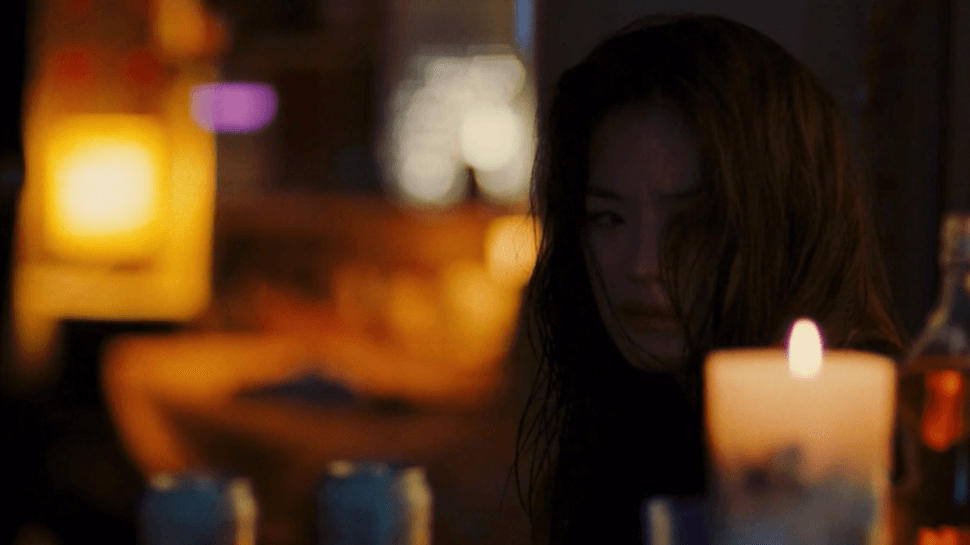

Hou’s carefully arranged aesthetics suggest his commentary through poetic interpretation. His visual techniques, conceived alongside his longtime cinematographer Mark Lee Ping-bin, include a combination of close-ups and vibrant, dreamlike colors paired with long unbroken sequences that emphasize temporality. Hou told Cinéaste, “I wanted to get very close to the main characters and I used an 85mm lens which enlarges the images of people—because it’s very narrow, they become larger than life. That’s the effect I wanted.” The closeness Hou mentions appears in several blurred sequences that seem initially abstract until they come into focus. In addition, Hou includes what scholar Brian Price calls “color abstractions”—moments where an ambiguous array of unfocused colors overcomes the frame. For example, one shot captures beads hanging out of focus in the foreground, looking like globs of light and color. Blurry shots explore the bright colors of Vicky’s room, and elsewhere, during a sex scene, wherein Vicky’s head hangs over the mattress’ edge, and from her perspective, we see a pulsing yellow-orange light in the foreground. The technique signifies Hou’s thematic agenda—that today’s events may seem hazy, but they become clear with time and perspective.

Hou admitted, “In general, the way I’d prefer to express myself in a film is not direct. It’s subtle—even vague, cloudy. There’s an imaginative space one can open up without directly saying it.” His poeticism emerges in a manner recalling his 1998 feature, Flowers of Shanghai, which unfolds over a series of extended takes. However, Millennium Mambo uses more than the mere 30 shots that comprise Flowers of Shanghai but fewer shots than the average film. The camera hovers over scenes, negotiating the space between characters instead of editing between them. In the language of French theorist Gilles Deleuze, what we see consists of both time-images and crystal-images. The time-image exists to evoke a sense of reality through the passage of time, represented by long, unbroken shots. The crystal-image contains a combination of the real and imaginary, which, as Deleuze writes, “has two definite sides” that condense the past and present, the dream and reality, into a single image. In Millenium Mambo, Hou’s entire film could be considered a crystal-image, remembered from 2011, with Vicky’s mind filling in the textured blank spaces between the events recalled in her voiceover. After all, memory is just an accounting of things that happened; cinema can capture their flavor, the substance between the major events cited in Vicky’s narration—even those she could not possibly remember, such as being blackout drunk at Jack’s place, or the nature of Jack’s telephone call to his criminal associates.

Hou admitted, “In general, the way I’d prefer to express myself in a film is not direct. It’s subtle—even vague, cloudy. There’s an imaginative space one can open up without directly saying it.” His poeticism emerges in a manner recalling his 1998 feature, Flowers of Shanghai, which unfolds over a series of extended takes. However, Millennium Mambo uses more than the mere 30 shots that comprise Flowers of Shanghai but fewer shots than the average film. The camera hovers over scenes, negotiating the space between characters instead of editing between them. In the language of French theorist Gilles Deleuze, what we see consists of both time-images and crystal-images. The time-image exists to evoke a sense of reality through the passage of time, represented by long, unbroken shots. The crystal-image contains a combination of the real and imaginary, which, as Deleuze writes, “has two definite sides” that condense the past and present, the dream and reality, into a single image. In Millenium Mambo, Hou’s entire film could be considered a crystal-image, remembered from 2011, with Vicky’s mind filling in the textured blank spaces between the events recalled in her voiceover. After all, memory is just an accounting of things that happened; cinema can capture their flavor, the substance between the major events cited in Vicky’s narration—even those she could not possibly remember, such as being blackout drunk at Jack’s place, or the nature of Jack’s telephone call to his criminal associates.

Given his aesthetic strategy, Hou even selected his title with care. The mambo dance, derived from the rhumba, and named after the 1938 song “Mambo” by the Cuban ensemble Arcaño y sus Maravillas, became a freeing and expressive style of dance. Although there is no mambo dancing in Millennium Mambo, Hou replicates a similar kind of emotive outpouring that he witnessed while researching his film. He hung out with young people at bars and clubs; he even tried Ecstacy, often finding himself lost in the perpetual rhythm of electronica music. But also, despite its more commonplace association with the Latin-American genre of music that originated in Cuba, the word “mambo” has a different meaning in Haitian Creole culture. There, “mambo” means “voodoo priestess.” How appropriate for Vicky, who casts a spell on both Hao-Hao and Jack, not to mention the audience. Hou portrays Vicky as both betwitching and lost, a kind of adrift enchantress. These two ideas behind “mambo” combine in symbolic terms by the finale, as Vicky transitions from Taipei to Yubari. Hou described this narrative trajectory in visual terms as “a tunnel in absolute darkness with a ring of light at the end of it.” To be sure, with Vicky’s move, Hou’s visuals transition from tight, confined setups in Taiwan to increasingly open-air and exterior shots in Japan, suggesting the freedom, independence, and relief of her new chapter in life.

But given its absence of narrative and character information, and its status as a primarily tonal piece, Millennium Mambo was not a major hit in Taiwan, selling only about 3,000 tickets, according to Hou. However, it was the first of Hou’s films to receive distribution outside of the festival circuit in the United States, creating newfound awareness and interest in his body of work. But even the US and Cannes Film Festival audiences met the film with, at most, mild praise. Writing for The New York Times, Elvis Mitchell called the film “superficially enjoyable, though not nearly as rich or resonant (or for that matter, as memorable) as his other work.” The Hollywood Reporter’s critic decried it as “a mind-numbing case of style over precious little substance.” Indeed, Lee Ellickson observed about the initial cut, which received a ten-minute trimming by Hou after the lukewarm reception, “Never has a Hou Hsiao-hsien film been greeted with such ambivalence as Millennium Mambo was at Cannes.” Price noted that critics “were puzzled by the disappearance of his long take, deep-focus explorations of Taiwanese and Chinese history.” And yet, it seems most critics missed that the subject of Millennium Mambo is the pace at which Taiwan was changing, and therefore Hou’s aesthetics would mirror that change.

With American, Japanese, and Korean pop culture heavily influencing Taiwanese culture, Hou sought to capture how people do not seize the advantages of the information age. Instead, there is only change for change’s sake, resulting in contrary stagnation. After the end of the White Terror, the cultural developments in Taiwan felt productive, like a movement toward freedom, progress, and national betterment. But Hou began to recognize that the changes had become inactive and no longer had meaning. Perhaps people had grown complacent, spending their nights in clubs and restaurants that would soon fold and be replaced by another. From within this inaction, Hou centers on a character who yearns for freedom. Vicky might even be seen as a stand-in for Taiwan, ever caught in the hold of various imperialist forces. Her reflection from 2011 suggests a hopeful time to come, far removed from 2001’s period of cultural inactivity and possession by others. For Vicky, the events in 2001 represent an objective past that she has long since moved beyond, and from Hou’s perspective, he yearns for a better future.

With American, Japanese, and Korean pop culture heavily influencing Taiwanese culture, Hou sought to capture how people do not seize the advantages of the information age. Instead, there is only change for change’s sake, resulting in contrary stagnation. After the end of the White Terror, the cultural developments in Taiwan felt productive, like a movement toward freedom, progress, and national betterment. But Hou began to recognize that the changes had become inactive and no longer had meaning. Perhaps people had grown complacent, spending their nights in clubs and restaurants that would soon fold and be replaced by another. From within this inaction, Hou centers on a character who yearns for freedom. Vicky might even be seen as a stand-in for Taiwan, ever caught in the hold of various imperialist forces. Her reflection from 2011 suggests a hopeful time to come, far removed from 2001’s period of cultural inactivity and possession by others. For Vicky, the events in 2001 represent an objective past that she has long since moved beyond, and from Hou’s perspective, he yearns for a better future.

To call Millennium Mambo misunderstood in 2001, or even today, is an understatement. Hou’s poetic style registers as a glossy, alluring daze upon first look, yet the film’s temporal conceit and states of reflection remark on Taipei from a fictional but optimistic tomorrow. Remote and drifting, Shu Qi’s Vicky seems to flounder between her work, Hao-Hao, and Jack with the same contemplative pattern that Hou’s camera explores the close-quartered spaces, softly floating from one position to the next in intimate proximity. Although it’s easy to lose oneself in Vicky’s pattern of behavior in what Hou called the “repetitive present,” the film’s lack of forward thrust, combined with its equal parts immersion in the present and reflection of the past, offer a sharp critique of contemporary Taipei—albeit with hope for what’s to come. This is achieved not through the film’s drama but the dramatic emptiness, since Vicky’s detached memory of the events take place in the past tense. Hou’s intentional distance requires more from the viewer, even though little seems to happen onscreen. Conveying an aura of wasted and trancelike youth, Hou makes the simplest of observations: the past is closed; the future is open.

(Note: This essay was originally posted to Patreon on April 26, 2023.)

Bibliography:

Ciment, Michel and Hubert Niogret. “Interview: Hou Hsiao-hsien.” Metrograph. https://metrograph.com/hou-hsiao-hsien/. Accessed 5 April 2023.

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta. University of Minnesota Press, 1989.

Ellickson, Lee, and Hou Hsiao-hsien. “Preparing to Live in the Present: An Interview with Hou Hsiao-Hsien.” Cinéaste, vol. 27, no. 4, 2002, pp. 13–19. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41689517. Accessed 5 April 2023.

Price, Brian. “Color, the Formless, and Cinematic Eros.” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, vol. 47, no. 1, 2006, pp. 22–35. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41552446. Accessed 5 April 2023.

Sklar, Robert. “Hidden History, Modern Hedonism: The Films of Hou Hsiao-Hsien.” Cinéaste, vol. 27, no. 4, 2002, pp. 11–12. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41689516. Accessed 5 April 2023.

Suchenski, Richard I., editor. Hou Hsiao-hsien. Austrian Film Museum, 2014.

Udden, James. No Man an Island: The Cinema of Hou Hsiao-hsien. Hong Kong University Press; Reprint edition, 2017.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review