The Definitives

Pan’s Labyrinth

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Made with the enthusiasm of a child and the artistry of a master, Guillermo del Toro’s El laberinto del fauno is a film so dedicated to making us dream that even its score is a lullaby. Drawn from uncountable sources and a lifetime of genre fascination, the Mexican filmmaker’s richly conceived fantasy creates a new postmodern mythology and establishes the picture as a landmark of the genre. Del Toro’s small but impactful presence in modern cinema has been nothing short of paramount, as he elevates the fantastic with vision, craftsmanship, and personal storytelling. In film after film, his protagonists are extensions of himself, actual or ostensible children who, like in some venerable fairy tale, discover an impossible world or learn that frightening creatures actually lurk in the dark. And with each new tale, he awakens the viewer’s imagination without sacrificing invention or dramatic authority.

Del Toro’s story takes place in 1944, when anti-Franco resistance fighters use a Spanish forest to conceal themselves and wait for Allied forces to liberate them. Arriving to hunt them down are a barrage of Franco’s troops led by the cruel Capitan Vidal (Sergi Lopez), a man ruled by his sadistic notions of order and family. Vidal establishes headquarters at an abandoned mill surrounded by archaic ruins and woodland, and has brought along his new wife, Carmen (Ariadna Gil), and her 11-year-old daughter from her first marriage, Ofelia (Ivana Baquero). His only interest in Carmen is their unborn child; his concern for Ofelia is even less. This is a pitiless man, one who brutally kills suspected freedom fighters only to discover that they are what they said, farmers out hunting rabbit; then he takes their modest game for his dinner. As his forces gradually converge on the resistance sheltered in the woods, he begins to suspect someone at the mill has been informing for the enemy. The head servant, Mercedes (Maribel Verdú), who has developed a rapport with Ofelia, supplies the rebel forces with antibiotics and intelligence. But Vidal remains fixated on the ill Carmen, whose weakness could cost him the life of his successor. “If you have to make a choice,” he tells the doctor, “save the baby.”

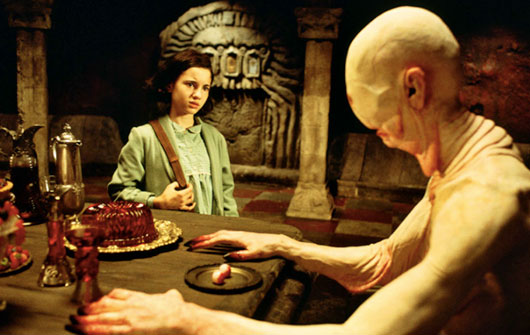

While Vidal advances his Fascist agenda, Ofelia, a natural dreamer, grows enchanted by the forest. She meets a stick bug of sorts that reveals itself as a fairy; it leads the child through the ruins of a nearby labyrinth to her first encounter with the Faun (Doug Jones), a creature born of mountains and earth, but whose intentions are suspect. The Faun tells Ofelia that she is Princess Moanna of the Underground Realm, a vast kingdom free of pain and death, and that to return home she must complete three tasks before the next full moon. For her first task, she must climb into a muddy passage of roots to collect an important key from a gluttonous toad, its presence killing a once magnificent fig tree. On her second assignment, with the toad’s key, she must enter the lair of a horrible creature called Pale Man (also Jones), unlock a safe box, and bring back the dagger inside without eating from the creature’s table. Ofelia’s temptation prevails, however, and she fails the Faun, who, in consideration of her mother’s death, resolves to give her another chance. He asks that Ofelia bring her newborn brother to the Labyrinth.

Del Toro weaves the two stories together with a close connection between Vidal’s violent war and Ofelia’s fantastical realm. Both are dangerous places for the girl, yet only her mythic world offers the possibility for escape, whereas any future with Vidal means certain doom for Ofelia and her mother. The Capitan’s forces have been crushed by the resistance and all seems lost. Vidal follows after Ofelia and his progeny to the Labyrinth, where she safeguards her only family and refuses to give her brother to the Faun. Close behind, Vidal reaches Ofelia in the Labyrinth and sees her talking to no one. After taking the child, he shoots her down. With her death and self-sacrifice for her innocent brother, Ofelia earns her throne in the Underground Realm as Princess Moanna, while above, the resistance disposes of Vidal and Mercedes mourns over Ofelia’s body. Against expectations, Ofelia’s magical world does not provide an all-protective sanctuary; its inhabitants are dangerous and even deadly, perhaps informed by unrelenting atrocities in her life—a father taken by war only to be replaced by a dogmatic madman; a mother who eventually dies during childbirth; a despotic guardian with no concern for human life. If Ofelia has dreamt up her world, then it has been influenced by the tragedies around her, leaving her to trust no one, not even her imagination. Only in death can her imagination truly save her.

Consider how the Faun emerges from the dark, eating some unidentified slice of flesh that he shares with a fairy, and then asks the girl to place herself in danger. Such a creature hardly seems escapist for a child, even a child like Ofelia, versed in storybooks. But then, with Vidal as a stepfather, even duplicitous and monstrous creatures might seem comforting by contrast. Later she embraces the Faun like an old friend. Del Toro wants us to question the nature of his story—whether or not Ofielia’s daydreams are imagined, or part of a greater world that only she can see because, indeed, she is Princess Moanna. He maintains a balance between the two worlds with a formal interconnectedness through editing, yet also distance. Fantasy scenes seem to unfold from Ofelia’s point of view only, though what could be considered the “reality” of Vidal’s war is verified through multiple perspectives (Vidal, Carmen, Mercedes, etc.). This is true except in two bookmarking scenes: the initial after Ofelia first meets the insect on the road and later just before the end credits, when the film’s perspective shifts to the insect-fairy, whose sole presence onscreen suggests a connection between the viewer and the fantasy world, therefore confirming its existence within the overall world of the film.

Though known in most circles as Pan’s Labyrinth, del Toro has pointed out that the mythical creature Pan never appears in the film, and that the central half-man, half-goat faun, or satyr, goes unnamed. The Spanish-language title translates to “The Faun’s Labyrinth”, which may have confused English-language audiences in its similarity to “fawn” or young deer, and so for marketing purposes the title was changed. However, del Toro is quick to point out that he specifically avoided including Pan in his story, as the Greek god associated with the spring season and fertility, as well as stories of bestiality and masturbation, would make unsettling company across from his 11-year-old protagonist. Instead, del Toro draws not only from Greek mythology, but from authors like Algernon Blackwood, Lord Dunsany, and Arthur Machen to conceive a tale ruled by a powerful mixture of myth and history that have fascinated the filmmaker since his youth.

As a child growing up in Guadalajara, Mexico, del Toro explored all things macabre, from horror movies to black magic to insects. Interested in seemingly all things morbid, his preoccupations concerned his parents who ultimately resolved that he was just “imaginative”. His fascination became a well-funded obsession once his father won the national lottery and could finance his son’s hobbies. After his first copy of the magazine “Famous Monsters of Filmland”, the young cineaste began drawing bizarre creatures and exploring methods of movie makeup—everything from vampire fangs to fake blood. He went to film school at the Centro de Investigación y Estudios Cinematográficos in Guadalajara, and after graduating, in 1985 he started Necropia, a special FX company based in Mexico City. Experiments with short films like Geometria, the horror movie equivalent of a dirty joke, led to the release of his first feature in 1993, Cronos, which won the Mercedes-Benz Award at Cannes and secured his future in Hollywood.

As a child growing up in Guadalajara, Mexico, del Toro explored all things macabre, from horror movies to black magic to insects. Interested in seemingly all things morbid, his preoccupations concerned his parents who ultimately resolved that he was just “imaginative”. His fascination became a well-funded obsession once his father won the national lottery and could finance his son’s hobbies. After his first copy of the magazine “Famous Monsters of Filmland”, the young cineaste began drawing bizarre creatures and exploring methods of movie makeup—everything from vampire fangs to fake blood. He went to film school at the Centro de Investigación y Estudios Cinematográficos in Guadalajara, and after graduating, in 1985 he started Necropia, a special FX company based in Mexico City. Experiments with short films like Geometria, the horror movie equivalent of a dirty joke, led to the release of his first feature in 1993, Cronos, which won the Mercedes-Benz Award at Cannes and secured his future in Hollywood.

During the heyday of practical makeup effects, ushered by H.R. Giger’s lurid designs for Alien, del Toro watched the masters at work and drew inspiration. Rick Baker’s work on An American Werewolf in London and Videodrome broke barriers in what movie makeup could do. Along with the film’s setting, Rob Bottin’s terrifying, morphing organism in John Carpenter’s The Thing helped echo a horrifying twist on H.P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness, a dream project for del Toro. Chris Walas transformed Jeff Goldblum into a human gradually trounced by insect DNA that overcomes his body like a disease, while Stan Winston created monster effects on Predator and robotics on The Terminator that changed the industry with their iconic appearance. Del Toro would join this list of landmark artists by ingraining his personal flourishes to the concepts of his makeup and creatures.

His seemingly endless scope of vision derives from mythical iconography, fairy tales, classical paintings, his favorite comic books and movies, and all things pulp. Yet, del Toro redefines such material through sizeable doses of pure imagination. Winding patterns in the Faun’s labyrinth or in the textures of both beautiful and horrible creatures are all rendered with the same sense of wonder and conceptual splendor, some derived, but always reinvented. From preproduction notebooks dating back to 1993, del Toro’s designs for El laberinto del fauno feel familiar in a way that cannot be pinpointed. Take the giant toad that offers up Ofelia’s crucial key; it looks like one from a dozen storybooks, but filtered through del Toro’s imagination to emerge altogether original. Del Toro seems to have obtained material from our collective dreams and reformed it into something completely new.

Another example, Pale Man, comes from a place both historical and personal for the director. Seated before a mountainous feast in his lair, the giant Pale Man looks revoltingly thin and, given folds of skin that drape his frame like a gown, appears to have been cursed to starvation. His body inert and hungry, he waits until an unwitting child eats from the lavish table of food and becomes his dinner. On a platter before him rest his eyes, which are inserted into sockets in his palms to peer with outstretched hands. Fresco murals on the surrounding walls depict ogres consuming children, and it becomes clear that del Toro has reimagined an even more nightmarish version of Francisco de Goya’s painting Saturn Devouring his Children. But the image also comes from a very personal place, as the director remembers drooping folds on his own body after losing much weight, and then recaptured the image here. Del Toro’s understanding of the body and its weaknesses, its ability to change, mutate, or be destroyed, informs his creation of such creatures, and also his resistance to CGI-based characters.

Another example, Pale Man, comes from a place both historical and personal for the director. Seated before a mountainous feast in his lair, the giant Pale Man looks revoltingly thin and, given folds of skin that drape his frame like a gown, appears to have been cursed to starvation. His body inert and hungry, he waits until an unwitting child eats from the lavish table of food and becomes his dinner. On a platter before him rest his eyes, which are inserted into sockets in his palms to peer with outstretched hands. Fresco murals on the surrounding walls depict ogres consuming children, and it becomes clear that del Toro has reimagined an even more nightmarish version of Francisco de Goya’s painting Saturn Devouring his Children. But the image also comes from a very personal place, as the director remembers drooping folds on his own body after losing much weight, and then recaptured the image here. Del Toro’s understanding of the body and its weaknesses, its ability to change, mutate, or be destroyed, informs his creation of such creatures, and also his resistance to CGI-based characters.

For del Toro, the more tangible the film’s fantastical elements appear, the more believable they are to the viewer. As a result, he has resisted complete conversion into computer animation on his productions, and even devoted most of his salary on Hellboy and all of it from El laberinto del fauno to complete practical monster effects that the studios refused to finance, but which he considered crucial to the audience’s suspension of disbelief. An audience can see through digitized artifice, and no matter how skilled the CGI, a viewer can always tell. Using former mime Doug Jones to play both the Faun and Pale Man under hours of makeup, and animatronics to fulfill other creatures, del Toro’s world in El laberinto del fauno has an earthy realism. Enhanced by the forest setting laden with fallen leaves and crumbling ruins, the mise-en-scène feels amassed by organic life. The Faun appears composed solely of forest components; even the computer-generated stick bug transforms into a fairy with leaves for wings. All of these details, along with the predominant natural surfaces that augment del Toro’s imaginative designs, give each of his films a substantial depth beyond any others in their genres.

Aside from Mimic (1997), a famously troubled production on which del Toro lost creative control to the studio’s demand for schlocky scares, and Blade II (2002), a studio project taken to advance his status as a bankable Hollywood genre filmmaker, the writer-director’s work has formed the signatures of an auteur—maybe the only auteur to work exclusively in the fantasy and horror genres. His films reintroduce us to classical storytelling in ways that at once feel ageless and yet entirely original. After its release in 2006, the enthusiastic reception of El laberinto del fauno, rare for such a dark and violent fantasy film, confirmed its ability to reach audiences worldwide with its imagination and heartbreaking dramatic consequences. The film received twenty minutes of applause at the Cannes Film Festival, where it was nominated for the Palme d’Or. At the Academy Awards, the film won three Oscars (for Best Makeup, Best Art Direction, and Guillermo Navarro’s cinematography) and was nominated for three more (Best Screenplay, Best Foreign Film, and Best Original Score). With El laberinto del fauno, Del Toro invites us to rethink enduring tales like Alice in Wonderland within our unforgivingly real world, where Fascism and fearful violence present a reality from which we must escape. Fortunately, del Toro’s rich mixture of treacherous politics and enlivened fantasy highlight the importance of escapism, while also challenging us to reflect on the limitless boundaries of imagination, which under his control, has just as much significance, if not more so, as reality.

Viewing after viewing, it is impossible to determine with certainty if the film’s fantasy world is part of Ofelia’s dreams or an actual subworld of mystical creatures and clever monsters. Just as del Toro enjoys exploring a child’s imagination, he revels more in the idea of pulling back the curtain to discover that our richest imaginings are actually real. Think about how Agent Meyers in Hellboy discovers the government’s best kept paranormal secret smoking cigars and tending to his cats, or how the boy in The Devil’s Backbone (the older brother of El laberinto del fauno) realizes that his innocent fear of ghosts is justified. And yet, such a clear distinction is not made in El laberinto del fauno. Del Toro employs measured wipes between worlds as opposed to concise cuts, their interconnectedness defined often in one full movement from the shadow of one world into another, as his film is about making a choice between two worlds. Just as Ofelia must decide whether or not to trust the Faun, the audience must decide if the Faun is truly there, or if she has dreamt this world merely as a way of escaping Vidal’s war.

Viewing after viewing, it is impossible to determine with certainty if the film’s fantasy world is part of Ofelia’s dreams or an actual subworld of mystical creatures and clever monsters. Just as del Toro enjoys exploring a child’s imagination, he revels more in the idea of pulling back the curtain to discover that our richest imaginings are actually real. Think about how Agent Meyers in Hellboy discovers the government’s best kept paranormal secret smoking cigars and tending to his cats, or how the boy in The Devil’s Backbone (the older brother of El laberinto del fauno) realizes that his innocent fear of ghosts is justified. And yet, such a clear distinction is not made in El laberinto del fauno. Del Toro employs measured wipes between worlds as opposed to concise cuts, their interconnectedness defined often in one full movement from the shadow of one world into another, as his film is about making a choice between two worlds. Just as Ofelia must decide whether or not to trust the Faun, the audience must decide if the Faun is truly there, or if she has dreamt this world merely as a way of escaping Vidal’s war.

Similarities between the worlds make our decision more complicated. Why, for instance, would Ofelia’s dreamworld contain a shifty Faun who seems to have ulterior motives? Why is her fantasy world not simply an escapist land free of fear and danger? And where does a child accumulate the material to imagine a creature as terrifying as Pale Man? Perhaps Ofelia is a mirror image of del Toro, a child curious about morbid things that inspire her imagination. The director has often been compared to a big kid, and by his own admission characters like Hellboy are infused with his own personality. For Ofelia, certainly men like Vidal and the atrocities around her have shaped her perception of reality and influenced her dreams, making the creatures of the Faun’s world elaborately designed and often untrustworthy, whereas the monsters of her imagination are more terrifying than even Vidal. They must be, for how else could Ofelia cope with the Captain’s sadistic treatment of her family and his subordinates, unless there was something out there even more terrifying than him?

Rather than choosing whether the fantasy elements of the film are Ofelia’s dreams or if they actually exist, there is a third option, perhaps informed by Christopher Nolan’s Inception. It may be that Ofelia’s dream world is born from her imagination, but after spending so much time there, it becomes preferable to the harsh realities around her. Del Toro would argue that reality is what we make it, and Ofelia has chosen the Faun’s world as part of her reality and a new beginning with her death—her entrance into that world ushered by the sweet humming of Mercedes’ lullaby, which is also the melody from Javier Navarrete’s haunting yet beautiful score. Because she believes in it, the world is real. What resounds as the lasting tragedy of Ofelia’s story is that even though her dreamworld in a sense “rescues” her from death, she cannot merely delete such notions from her thought—the world’s monsters have crept into her unconscious and fill the dark places of her dreams. Those two worlds are so unalterably linked in her mind that even her wildest visions cannot protect her, not entirely, from reality’s cruel influence.

After French author Charles Perrault domesticated the gruesome, dark fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm into versions suitable for bourgeois families, Guillermo Del Toro returns fairy tales back to their deathly origins. Each one of del Toro’s mythologies has a graceful way of being familiar yet altogether new, but his greatest such accomplishment remains El laberinto del fauno, a film that channels a dozen fairy tales but paradoxically stands on its own as a true original. Through a realistic backdrop punctuated by dramatic storytelling, tragedy, and violence, del Toro engages the imagination with the fantastic. At once, his film underscores the importance of escapist fantasy through a horrifying real-world parable, yet tells its own fairy tale in the process, one with imagery so memorable and powerful that it could last beyond cinema, into an oral tradition reserved for campfires and bedtime.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review