Chimeras of Independence in Ritwik’s The Cloud-Capped Star

By Maaisha Osman | September 6, 2021

Meghe Dhaka Tara (The Cloud-Capped Star, 1960), by visionary Bengali filmmaker Ritwik Kumar Ghatak, or just Ritwik for Bengalis, powerfully captures the despair of being in a constant state of transience. It’s a film about the pervasive sense of embitterment over the newly drawn border and the traumatic terms on which independence from British rule had finally been won in India. Undivided Bengal was perceived in British India as a region with sectarian conflicts between Hindu and Muslim segments of the population—incorporated within a Bengali cultural and linguistic identity but carved into two separate territorial entities in 1947. East Bengal (now Bangladesh) formed the eastern wing of Pakistan, and West Bengal became a part of India. Bengalis such as Ritwik—who migrated to West Bengal during the 1940s but had deep roots in East Bengal—saw their homeland become a foreign country overnight. Many refugees settled in Calcutta, taking over swampy land in the eastern peripheries of the city to build ‘refugee colonies’—the crumbling settlements that we see in Meghe Dhaka Tara—and struggling to maintain their dignity.

Meghe Dhaka Tara tells the story of Neeta (Supriya Choudhury), the eldest daughter of a downwardly mobile Hindu middle-class family, who barely keeps her family afloat. Her family has been dislocated by the partition of India and trying to survive in refugee settlements in the rural periphery of 1950s Calcutta. Udbastu is the word Ritwik used for refugees—meaning someone displaced from their ancestral home (bastu). Neeta is portrayed as a provider and a nurturer forsaking her dreams as the family becomes more and more reliant on her earnings. Ritwik uses the shattered family as an allegory for the exile and partition, confronting bigotries and social attitudes ingrained within Bengali culture at the time. The visual details show a young working woman with bags on her shoulder and broken slippers, lines on her drained face, and pounded by tempests. She is seemingly ordinary yet astonishingly resilient. These images set the stage for the osmotic interplay of myth and mundanity in Meghe Dhaka Tara. As film scholar Manishita Dass powerfully stated, “metaphors and mythic motifs are not imposed on the everyday but emerge out of it, endowing it with heightened significance and connecting the individual to the collective without transforming the real human being into metaphorical cipher.”

Ritwik’s East Bengal, where he spent much of his childhood, is a lost arcadia—a dreamy, fertile land of open spaces, magnificent river deltas, engrained communities, and chaotic affairs. He called the 1947 partition of the Indian subcontinent “the great betrayal,” blaming it on the materialist, immoral, petit-bourgeois Bengali contemporaries that defined Calcutta. It was one of the largest mass displacements of modern history, concerning an estimated 12 to 15 million people, accompanied by the cruelty of the Bengal Famine of 1943, the havoc of World War II, and then communal violence, resulting in the deaths of 500,000 to a million people. The post-independence predicament of the divided and weakening Bengal haunted Ritwik until his death in 1976 at the age of 51. He was concerned with the socio-economic issues and spiritual alienation and cultural deracination from this violent uprooting. He described the magnitudes of rootlessness: “People’s ways of thinking have changed, their hearts have changed, their souls have changed… their cultural consciousness has putrefied, and their umbilical ties with their past completely severed.” Ritwik’s trilogy—Meghe Dhaka Tara (The Cloud-Capped Stars), Komal Ganghar (A Soft Note on a Sharp Scale), and Subarnarekha—deals with the aftermaths of partition in Bengal, with vigorous motifs on melodrama and realism, with Marxist perspectives, and unsettling moments of Brechtian alienation.

Ritwik’s East Bengal, where he spent much of his childhood, is a lost arcadia—a dreamy, fertile land of open spaces, magnificent river deltas, engrained communities, and chaotic affairs. He called the 1947 partition of the Indian subcontinent “the great betrayal,” blaming it on the materialist, immoral, petit-bourgeois Bengali contemporaries that defined Calcutta. It was one of the largest mass displacements of modern history, concerning an estimated 12 to 15 million people, accompanied by the cruelty of the Bengal Famine of 1943, the havoc of World War II, and then communal violence, resulting in the deaths of 500,000 to a million people. The post-independence predicament of the divided and weakening Bengal haunted Ritwik until his death in 1976 at the age of 51. He was concerned with the socio-economic issues and spiritual alienation and cultural deracination from this violent uprooting. He described the magnitudes of rootlessness: “People’s ways of thinking have changed, their hearts have changed, their souls have changed… their cultural consciousness has putrefied, and their umbilical ties with their past completely severed.” Ritwik’s trilogy—Meghe Dhaka Tara (The Cloud-Capped Stars), Komal Ganghar (A Soft Note on a Sharp Scale), and Subarnarekha—deals with the aftermaths of partition in Bengal, with vigorous motifs on melodrama and realism, with Marxist perspectives, and unsettling moments of Brechtian alienation.

The film’s opening sequence features a striking shot of a symbolic banyan tree against the morning sky, shadowing the fertile land beneath. The camera slowly glides towards the bottom right corner of the frame, where we see Neeta’s brother Shankar (Anil Chatterjee) sitting by the riverbank, reciting the “Rāga Hamsadhwani” (“The Call of Swans”). We hear fragments of this rāga throughout the course of the film, mostly used during daylight and open spaces. The first glimpse of Neeta associates her with the elements of nature as a nurturer, symbolizing the principles of fertility—she walks towards the light and closer to the camera, at first just the silhouette of a white saree, which only becomes Neeta when the first close-up reveals her traits. Her unforgettable smile when she stops to look at her brother practicing scales, and the noise of an approaching train, anchors the film’s mise-en-scène, transporting us to the world of a refugee colony. Film scholar Omar Ahmed considered trains an iconographic aspect of Bengali cinema, usually standing for modernity, as in Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy. However, Ritwik’s train has morphed into a motif of exodus following the trauma of partition.

We embark into the world of the everyday through a momentary encounter between Neeta and the neighborhood grocer, Banshi, when he brusquely demands that she settle her family’s outstanding dues. The dialect he uses to address her as Didi-thairan (elder sister) can be identified as Bangal—a word West Bengalis use to denote eastern Bengalis. The exclusive use of colloquial Bangal instead of West Bengal standardized Bengali identifies them as refugees from East Bengal. The camera follows her as she walks down an unpaved road and suddenly staggers on her worn-out slippers, picks them up, and continues walking barefoot. In Manishita Dass’ words, this scene, “reminiscent of Van Gogh’s painting of a pair of worn-out boots, disclose[s] a history of toil, tenacity and economic hardship.” The scene reemerges at the end of the film in a poignant echo, bringing the collective dimension of this history to the fore. In Ritwik’s depiction of Neeta, the characteristics of the ‘idealized Bengali woman’ are poise under burden, a quiet dignity, and a paradoxical combination of tenderness and perseverance that evokes the history of pain. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak used the term “subaltern” to describe the often disregarded and marginalized position of ‘Third world woman’ in the wider context of Eurocentric feminist thought and colonialist ideology. Spivak maintains, “Western feminism has itself fallen prey to its own work by claiming to speak for all women when it often excludes the experiences of Asian, African and Arab woman.” Ritwik’s work not only reflects the postcolonial resistance identified by Spivak but recognizes that such women have been erased from history.

No place evokes women’s forgotten words as much as the courtyard. This center of colonial and post-colonial domestic life was represented in ‘40s and ‘50s Bengali cinema as a sacrificial space, populated by long-suffering girls and women. Ritwik uses the courtyard in the household as a space of enclosure and exploitation. The sociopolitical chaos and moral perplexity within interpersonal entanglements during that time cannot be more apparent than in the characterization of Neeta’s mother (Geeta Dey). Rancorous, cantankerous, acid-tongued, and tense bodied—she embodies the monotony of impoverishment. The shock of dislocation hardens her heart, making her increasingly selfish and harsh in her dealings with Neeta. Many of the crucial scenes that establish Neeta’s role as a nurturer of her family and fulfilling her mother’s and younger siblings’ selfish demands are played out in the home’s central courtyard. Later in the film, Neeta exiles herself to a room near the house entrance, suspecting that she might be suffering from tuberculosis. When her mother asks her why she is moving to the barbari—meaning outer quarter in colloquial Bengali—Neeta replies with a tormented voice: “This is a friendless house. What is the difference between barbari and andarbari (inner quarter)?” At this point, Ritwik makes it clear that home for Neeta is not a shelter in a heartless world but a site of ensnarement, exploitation, and estrangement.

No place evokes women’s forgotten words as much as the courtyard. This center of colonial and post-colonial domestic life was represented in ‘40s and ‘50s Bengali cinema as a sacrificial space, populated by long-suffering girls and women. Ritwik uses the courtyard in the household as a space of enclosure and exploitation. The sociopolitical chaos and moral perplexity within interpersonal entanglements during that time cannot be more apparent than in the characterization of Neeta’s mother (Geeta Dey). Rancorous, cantankerous, acid-tongued, and tense bodied—she embodies the monotony of impoverishment. The shock of dislocation hardens her heart, making her increasingly selfish and harsh in her dealings with Neeta. Many of the crucial scenes that establish Neeta’s role as a nurturer of her family and fulfilling her mother’s and younger siblings’ selfish demands are played out in the home’s central courtyard. Later in the film, Neeta exiles herself to a room near the house entrance, suspecting that she might be suffering from tuberculosis. When her mother asks her why she is moving to the barbari—meaning outer quarter in colloquial Bengali—Neeta replies with a tormented voice: “This is a friendless house. What is the difference between barbari and andarbari (inner quarter)?” At this point, Ritwik makes it clear that home for Neeta is not a shelter in a heartless world but a site of ensnarement, exploitation, and estrangement.

Ritwik creates an association between brewing sounds and Neeta’s mother to suggest a life fuming with displeasures in which her greater sentiments are crushed. The archetypal disguise of the atrocious mother is reflected on her tense face and distorted by her everyday struggles. Ritwik uses a similar combination in the film’s symbology of the goddess Uma to emphasize the sorrows and the ironies of Neeta’s dilemma. The symbology of Uma renders a rich vein of Bengali folklore: The tale follows the uniquely tender and affectionate daughter Uma, the only child of her parents, Giriraj (Lord of the Mountains) and Meneka, who regretfully give their daughter away in marriage to Lord Siva. Siva features in this myth as an old and reckless husband to Uma. The autumn festival in Bengal, known as Durga Puja, celebrates Uma’s return to her parental home. Bengalis worship idols of Durga for four days, during which āgōmōni songs rejoice her return and bījōyā songs mourn her departure. Many scholars have argued that āgōmōni and bījōyā songs echo the practice of child marriage in early medieval Bengal known as gauridān. Ritwik himself said that he reimagined Neeta as an agent of the young Bengali girls given away in gauridān over hundreds of years.

The withering of Neeta’s personal worth and distinct identity echoes in the eponymous expression that her would-be lover Shanat uses to describe her. In a letter, he writes: “I didn’t appreciate your worth at first. I thought you were like others. But now I see you in the clouds, perhaps a cloud-capped star veiled by circumstances, your aura dimmed.” The romantic metaphor attains a distressing irony in a series of events that include Shanat’s betrayal. When Neeta’s youngest brother Montu and their father suffer debilitating accidents, she sacrifices her postgraduate studies to become the sole breadwinner for the family. Reluctant to wait for Neeta, Shanat marries her sister Geeta (Gita Ghatak) with support from Neeta’s mother, who believed this a seamless solution to her predicament. Neeta’s father (Bijon Bhattacharya), a decaying schoolteacher, associates her with gauridān. At the same time, he watches Geeta’s wedding preparation and expresses with a sense of vulnerability: “In the past, people would marry their daughters off to dying men. They were barbarians. Today, we are educated and civilized, so we educate our daughters and then wiring them dry, put them to the grind, and wipe out their futures: That is the only difference.” Even today, his comment opposes the linear narrative of social progress and women’s rights in Bengal. Despite Neeta’s education and employment, and everything that differentiates her from gauridān, she is still subject to exploitation of new forms of patriarchal ethos and the network of familial relationships.

However, Neeta’s situation is not unchangeable. Ritwik uses visual and aural symbols to demonstrate that she still has a chance to grow and evolve. Consider the house’s layout: clay, hay, bamboo, and cane mirroring impermanence. And consider the distinctive sound of refugee colonies: school children singing the national anthem of newly-formed India and reciting their multiplication tables, the chirping of crickets, and the howling of an owl at night. These factors contribute to the symbolic nuance of how the socio-historical forces reshape the internal space. One cannot forget the scene of enigmatic reawakening of the chorus of crickets, when Neeta’s father recites the well-known poem by John Keats, “On the Grasshopper and Cricket,” to celebrate her birthday by the lake proclaiming the first lines, “the poetry of earth is never dead.”

However, Neeta’s situation is not unchangeable. Ritwik uses visual and aural symbols to demonstrate that she still has a chance to grow and evolve. Consider the house’s layout: clay, hay, bamboo, and cane mirroring impermanence. And consider the distinctive sound of refugee colonies: school children singing the national anthem of newly-formed India and reciting their multiplication tables, the chirping of crickets, and the howling of an owl at night. These factors contribute to the symbolic nuance of how the socio-historical forces reshape the internal space. One cannot forget the scene of enigmatic reawakening of the chorus of crickets, when Neeta’s father recites the well-known poem by John Keats, “On the Grasshopper and Cricket,” to celebrate her birthday by the lake proclaiming the first lines, “the poetry of earth is never dead.”

On a lone winter evening, when the frost

Has wrought a silence, from the stove there shrills

The Cricket’s song, in warmth increasing ever…

While the nocturnal noise of the crickets plays a central role in creating a sense of imminent misfortunes, Ritwik uses non-diegetic sound to connect Neeta’s agony to a larger historical trauma—the overwhelming sound of whiplash used at the film’s three dramatic high points. The idea of the whiplash was inspired by a 1943 Bengali poem “Madhu Banshi-r Goli” by Sombhu Mitra. The poem reflects the socio-economic mayhem of wartime Calcutta, when Congress and the Muslim league tore the region into two independent fragments, and it pays homage to revolutionary dreams of a better world. Bengali film historian Chidananda Dasgupta wrote that the dramatized sound of whiplash is “one of the very few alienated, intellectualized moments in Ghatak’s work.”

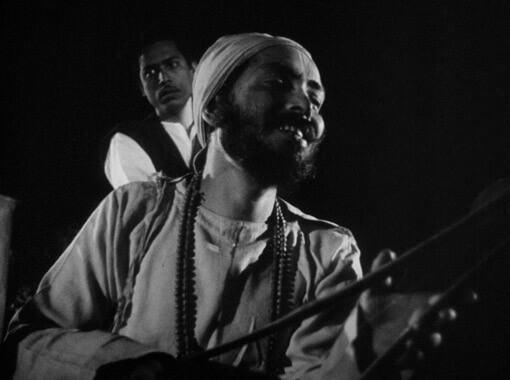

In a different aural flourish, one of the most prominent musical moments of the film is a haunting Bengali folk song, or eternal river song, that brings back memories of a lost homeland. It’s sung by Ranen Roychowdhury, a gifted folk musician from Bengal who also plays the singer in this sequence. The music starts in the background, during a rough encounter between the neighborhood grocer Banshi and Shankar, leading to a series of tense exchanges within the family. Then, we gradually see a group of four folk musicians appear in the backdrop, singing a song that brings back the memories of a lost homeland into the refugee colony. Roychowdhury’s desire for freedom is only heightened by the certainty that it will not come. A cry from the heart, his eyebrows rise, but his eyes remain closed to the world of corrupted promises.

I wasted all my good days

Now, in bad times,

I’ve come to the banks of the river of life

Boatman, I don’t know your name

I cry helpless tears on the banks of the river of life

Who will take you across, my heart?

Roychowdhury was known for the authenticity of his singing style and a voice that evokes the riverine space of his native Sylhet (now a district of Bangladesh). Like Ritwik, he grew up in East Bengal and moved to Calcutta during the Partition. The song is in bhātiyali—a traditional form of folk music that consists of metaphorical and emotional verses usually sung by boatmen during the journey across rivers during flood season. It is as if the wandering folk musician remembers the waters of his native region, which are now artificially separated from their original inhabitants. The memory of this free and borderless nature appears for a moment to bring together divided Bengal.

Roychowdhury was known for the authenticity of his singing style and a voice that evokes the riverine space of his native Sylhet (now a district of Bangladesh). Like Ritwik, he grew up in East Bengal and moved to Calcutta during the Partition. The song is in bhātiyali—a traditional form of folk music that consists of metaphorical and emotional verses usually sung by boatmen during the journey across rivers during flood season. It is as if the wandering folk musician remembers the waters of his native region, which are now artificially separated from their original inhabitants. The memory of this free and borderless nature appears for a moment to bring together divided Bengal.

The unfiltered authenticity of folk music is juxtaposed against a more theatrical melodramatic style that Ritwik employs to emphasize significant sequences in the film. During his tenure at the Indian People’s Theater Association (IPTA), he fused several models ranging from Brecht’s epic form to Bengali traditional folk form known as jātra. In numerous interviews and essays, Ritwik discussed how Brecht’s epic approach influenced his work. He believed that genuine audience engagement could only be achieved by alienating the spectator and emphasizing narrative non-linearity, anti-realist staging, expressionistic performance styles, fluid yet disorienting movement between contiguity and detachment, and the diegetic and non-diegetic use of aural motifs. Ritwik’s frequent use of wide-angle lenses, placement of the camera in irregular angles, rack focus, dramatic close-ups—all these techniques emerge out of the blend of Brechtian theatrical and cinematic forms.

A remarkable example of Ritwik’s continual collision between theatrical and cinematic forms can be seen in one of the most poignant sequences in the film, which relies on a specific kind of cultural knowledge and cinematic staging that carries the soulful and distinctive rendition of Rabindrasangeet, known as Tagore songs. Neeta’s brother Shankar proclaims to leave the household as a protest for the wrongdoings done to her. Neeta, in despair, then asks Shankar to teach her a Tagore song instead of responding directly to his proclamation.

The night when the storm tore down my doors

You came to my home, unbeknownst to me

The lamp went out, and it became dark,

I stretched out skywards, though I did not know for whom.

I lay in the unbridled dark, wanting this to be a dream,

I knew not that storm was your pennant for your triumph,

As dawn broke, I saw you standing there,

At the heart of desolation engulfing my home.

The cinematography in this scene is astonishing and evokes a sense of distress, but also emotional communion between Neeta and Shankar, and solace in art. Both are seated next to each other when the camera floats along in a dimly lit room, creating a willowy movement through its fluid use of lenses. It is perhaps the most poignant moment in the film, which no dialogue could have better articulated. The mechanisms of musical allusiveness, glimmers of moonlight through the bamboo walls, use of theatrical flourishes in the camerawork are heightened by the performances, lighting, editing, and the soundtrack in a glorious convergence. At the closing lines of the song, Neeta repeats the last lines with a broken voice. Suddenly, the violent whiplash sound cracks, and the camera cuts to her upturned face, and the scene almost mimics the promise of redemption offered by the last lines in the Tagore song. This is the first time in the film Neeta bursts into tears. The audience is left in a state of heightened emotion, connecting Neeta’s pain not only with the family’s oppressive structure but also with the post-independence predicament of a “divided, debilitated Bengal.” The rāgas, folk music, and Tagore songs intertwine with choric chants, ambient noises, and sound effects—thus creating an intense musical dialogue in the film. This dialogue gives voice to the unspoken thoughts and emotions of the characters situating heartbreaks in a wider social and cultural context.

The use of aural and musical motifs in the film alters the imagery into an almost transcendent allegorical significance while connecting it to performances of Hindustani classical music. The entire visual, musical, and aural compositions thus collide, interact, and evolve, creating symbolic associations that cannot be reduced to linear reasoning. Rāga verses, a unique feature of the classical Indian music tradition, are used throughout the film, and its performance is ornamental. The start is slow and then moves into a more expansive and rhythmic mode, gradually increasing in tempo to reach a fervent climax before collapsing into silence. In Indian tradition, rāgas are contemplated to have the power to color the mind. Ritwik uses fragments of the “Rāga Hamsadhwani” (“The Call of Swans”) during the film to evoke certain feelings and ideas within the spectators, as well as establish a symbolic association with season and time. The development of the rāga through fragments establishes Shankar’s progress as an artist. In the beginning of the film, when we see him practicing his scales by the lake, he sounds unsure and stops midway to pick up the melody again. At the end of the film, the melody reaches its complete expression and confidence when Shankar returns to the refugee colony after establishing himself as a successful singer in Bombay—in sharp contrast to his sister’s plunging trajectory.

The use of aural and musical motifs in the film alters the imagery into an almost transcendent allegorical significance while connecting it to performances of Hindustani classical music. The entire visual, musical, and aural compositions thus collide, interact, and evolve, creating symbolic associations that cannot be reduced to linear reasoning. Rāga verses, a unique feature of the classical Indian music tradition, are used throughout the film, and its performance is ornamental. The start is slow and then moves into a more expansive and rhythmic mode, gradually increasing in tempo to reach a fervent climax before collapsing into silence. In Indian tradition, rāgas are contemplated to have the power to color the mind. Ritwik uses fragments of the “Rāga Hamsadhwani” (“The Call of Swans”) during the film to evoke certain feelings and ideas within the spectators, as well as establish a symbolic association with season and time. The development of the rāga through fragments establishes Shankar’s progress as an artist. In the beginning of the film, when we see him practicing his scales by the lake, he sounds unsure and stops midway to pick up the melody again. At the end of the film, the melody reaches its complete expression and confidence when Shankar returns to the refugee colony after establishing himself as a successful singer in Bombay—in sharp contrast to his sister’s plunging trajectory.

Eventually, Neeta contracts tuberculosis. Upon learning of her illness, her father acts with rage and mournfully suggests that she leave home. The heartless act is a contradiction: it’s driven by love for his daughter and grief over his inability to protect her. The English-language subtitles cannot perfectly capture the moment when he intends Neeta to leave and says: “A child will be born in this house,” meaning he is actually questioning his family’s rightness to nurture a newborn in this house. Neeta picks up her most treasured belonging—a photograph with her brother in the mountains taken during a trip to a hill station. She shares her fondness for the mountains with Shanat at the beginning of the film, and she cherishes the memory of watching a picturesque sunrise from a mountain peak after a long hike. Later, in another scene, she tells Shankar about her dream to revisit the mountains when he becomes successful. Neeta’s childlike plea to her brother to take her to the mountains might remind a Bengali viewer of Bibhutibushan Bandopadhyay’s Panther Panchali (The Song of the Roads), the classic novel that inspired Satyajit Ray’s first film. In the novel, ill teenager Durga, who lives in a rural village, tells her brother Apu about her dream to see a train when she recovers. Ultimately, Durga dies without seeing a train (unlike in the film). In Ritwik’s film, Neeta finally sees the hills from a sanatorium, the place of her death.

Towards the end of Meghe Dhaka Tara, we see Neeta sitting on a rock as her brother Shankar visits her at the sanatorium in the hill station of Shillong (the northeast part of India and the capital of Meghalaya). Shankar tries to distract her with chitchat and share amusing details about their mischievous nephew, Geeta’s son, a toddler. Neeta smiles at first, but then she suddenly cries out and breaks down to her brother, “But I did want to live! Please tell me that I will live, just tell me once that I will live!”

Her desperate cry echoes through the landscape as if the mountains endure the pain with her. The camera scans the surroundings in a 360-degree turn. Manishita Dass beautifully wrote in her book about the film that the echoes reminded her of lines from a well-known Bengali poem, “Janani Jantrona” (“Mother Misery”): “I asked for life but only got the keening of the wind.” Dass writes, “Through this hyper-melodramatic articulation of Neeta’s desire to live, Ghatak not only expresses his personal anguish over the Partition but also registers his protest against what he deemed to be a mockery of independence and the ongoing destruction of a collective way of life.” Neeta’s disembodied voice evokes the shattered dreams of a generation of displaced Bengalis caught in the conflicts of history. Brilliant, curious, and creative students gave up their dreams of becoming historians or mathematicians to take on familial responsibilities in the wake of their newly formulated country. They have suffered and accepted their fate in silence with discreet courage and distressing grace, similar to Neeta’s reaction to adversity. Meghe Dhaka Tara leaves us in the theater of history with a timeless appeal, denouncing the injustices and betrayals of every day, endured by women like Neeta not only in Ritwik’s time but also in our own.

Bibliography:

Ahmed, Omar. Studying Indian Cinema. Columbia University Press, 2015.

Dasgupta, Chidananda. “Cinema, Marxism, and the Mother Goddess.” India International Centre Quarterly, 12.3 (1985): 249-264.

Dass, Manishita. The Cloud-Capped Star (Meghe Dhaka Tara). Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020.

Mukherjee, Victor. “The Muted Voice of a Refugee Woman: Looking at Ritwik Ghatak’s Meghe Dhaka Tara through the Feminist Lens.” The Criterion: An International Journal in English Vol. 8 (2017): 976-8165

Raychaudhuri, Anindya. “Resisting the resistible: re-writing myths of partition in the works of Ritwik Ghatak.” Social Semiotics, 19.4 (2009): 469-481.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty, and Graham Riach. Can the subaltern speak? Macat International Limited, 2016.

Maaisha Osman is a health care journalist based in Boston. She has written for Boston Globe Media’s STAT News, Scope, and Point of View Magazine. A lifelong cinéphile, she dreams of writing book of essays on films by her favorite directors like Ingmar Bergman, Andrei Tarkovsky, Satyajit Ray, Rwitik Ghatak, François Truffaut, Wong Kar-wai, and others.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review