The Definitives

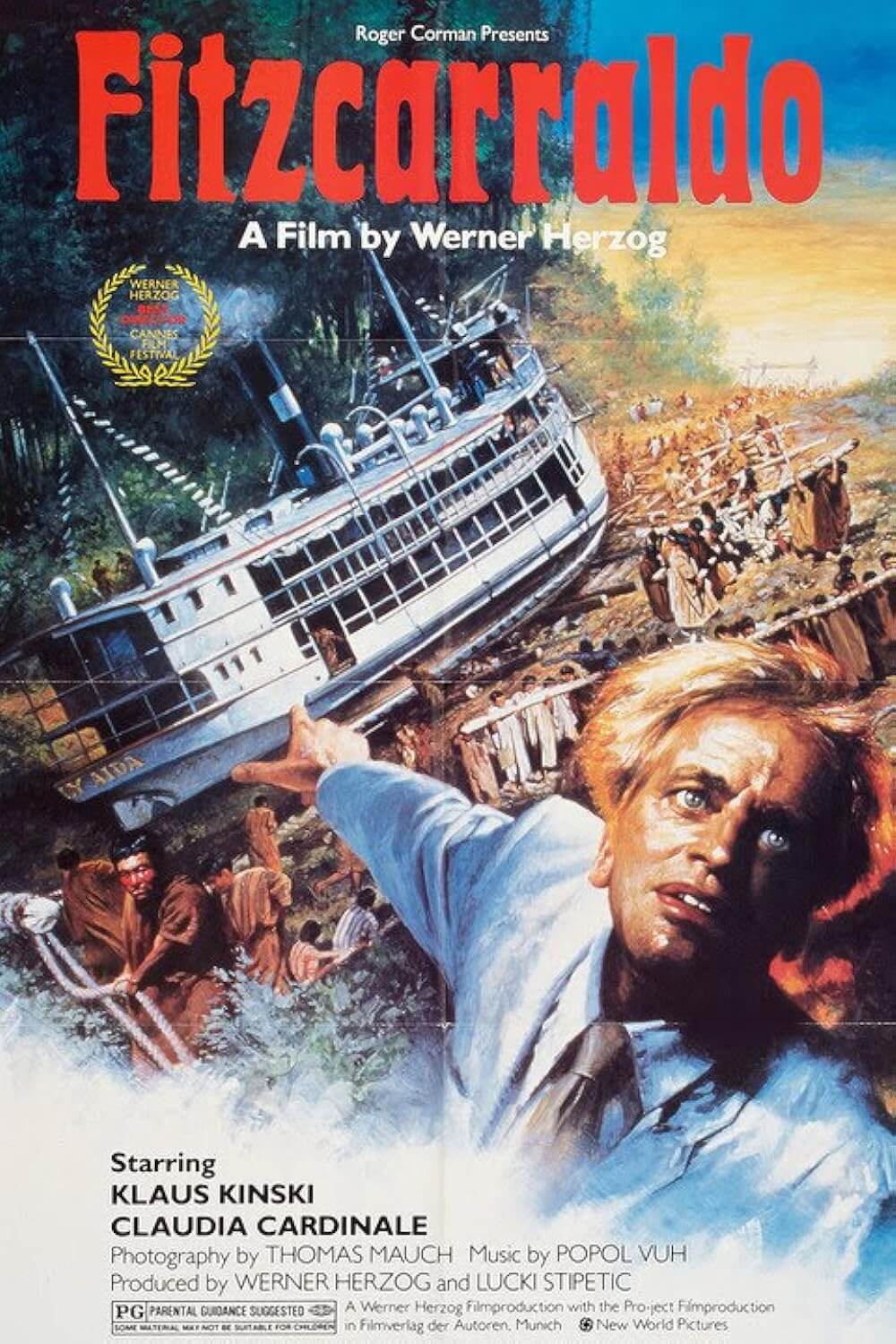

Fitzcarraldo (1982)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

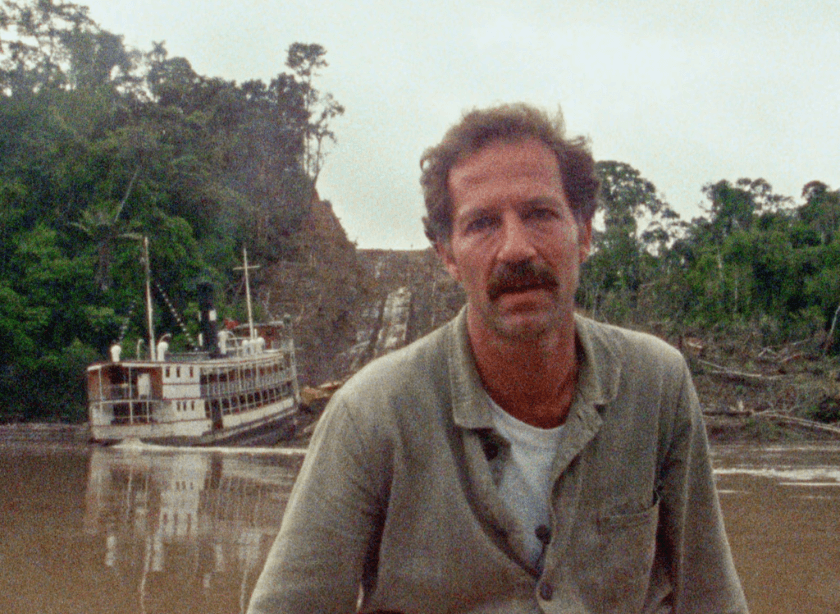

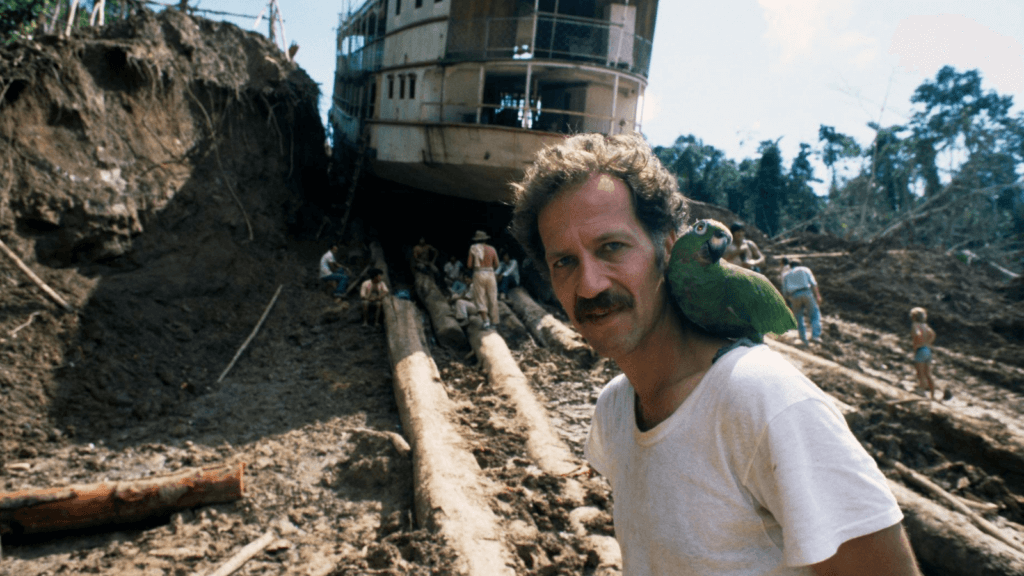

Few motion pictures have captured the frenzied power of obsession with as much veracity as Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo. Just as the film portrays a mad enthusiast determined to build an opera house in the middle of the Amazon jungle, the making of the film involved a director—who has often been called megalomaniacal, enigmatic, disciplined, and psychotic—bent on telling this story as truthfully as possible. For Herzog, whose films often walk the line between reality and fiction, this meant carrying out his protagonist’s same mission in the real world and filming the result. Herzog’s four-year production, spanning 1978 to the film’s 1982 release, is among the most infamous in film history. After an endless series of crises that, in many ways, the director propelled, Herzog emerged to call his film “a great metaphor”. For what, he cannot say. But the imagery and storytelling prove undeniably powerful. To this day, Herzog remains scarred from the production, perhaps because completing this film under such constant duress established his identity as a filmmaker and storyteller. After Fitzcarraldo, his output would dwell almost exclusively on the film’s theme of human conceit in the face of Nature.

Herzog’s story was inspired by Carlos Fermín Fitzcarrald, a rubber baron who moved a 32-ton boat over a hill between two Amazon tributaries. Herzog’s script grew from this idea and swelled into a tale about a man’s dream of building an opera house in the Amazon jungle, if only to invite his idol, Italian tenor Enrico Caruso, for opening night. Klaus Kinski plays Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald, whose name, “Fitzcarraldo,” was given by locals who could not pronounce “Fitzgerald”. He first appears emerging from the darkness in a boat on the Amazon. His motor has died, and Fitzcarraldo has come 1,200 miles, his hands bleeding, having rowed much of the way just to see Caruso perform. But he arrives late, yet is content to stand in the back and listen. Already, his irrational passions and his lot to fall short of them define the character. Though he has earned money with an ice-making machine, the crestfallen Fitzcarraldo is famous for his failed Trans-Andean Railway, which was supposed to connect Argentina and Chile by a rail through the Andes. Now he aspires to bring Caruso to Iquitos by building an opera house, a dream in which no one but him believes. His mistress, Molly (Claudia Cardinale), a bordello Madame in Iquitos, introduces him to a rubber baron investor who backs Fitzcarraldo’s purchase of a 400-square-mile plot of land rich with rubber trees. The land is thought to be unreachable because of the nearby rapid waters; however, a parallel tributary offers a solution:

Bring a boat down the calm tributary, heave the boat over a relatively narrow one-mile stretch of land, up a forty-degree incline of muddy earth, and down the other side, and reach the parallel river to access the rubber. To complete this undertaking, Fitzcarraldo purchases a steamer and takes it downriver with a crew, and when he arrives at the narrow point of land between rivers, he enlists native Amazonian tribes to complete the manual labor. Believing the white-haired Fitzcarraldo and his bright boat are holy envoys, they agree to work for him. After months of toiling that leaves workers dead and dozens of others polluted by the presence of so-called civilization in the wild, Fizcarraldo’s boat reaches the top using a complex system of pulleys, wooden cranks, and manpower. But when it finally touches the water on the other side, the local tribes, believing the boat must continue on to the next world, release it down the rapids, the Pongo das Mortes (the Rapids of Death), with only Fitzcarraldo inside. He survives, and resolves to bring the opera to Iquitos under less ideal circumstances, but no less glory—he drives an orchestra and singers up and down the river on the remains of his ramshackle boat, to play for a shoreside audience.

Had Herzog shot the film as Hollywood wanted, with a plastic boat streaming down a river set-piece, the audience would have seen right through the deceit of the moment. For his production, Herzog intended to drag an actual boat over a steep, muddy, and unreasonable slope in the middle of the Amazon rainforest. But Herzog’s production established a far more difficult task than Carlos Fermín Fitzcarrald, or even his character Fitzcarraldo would attempt. The real-life story involved a much lighter, 32-ton boat that was disassembled, sent over the mountain in pieces, and reassembled on the other side. Herzog wanted his boat to remain intact throughout its crossing, so the audience never loses touch with that resonant image as workers toil to lift it across impossible terrain. He did this not for realism, but for truthfulness—the truth the audience feels when they witness the spectacle onscreen. With the finished film, Herzog wanted the audience to feel the struggle and, with every frame, realize the determination required to assemble the pyramids of Giza, erect Stonehenge, pull this boat over the mountain, or even complete this film. When Herzog could not find a boat to use on the film, he resolved to build a 340-ton steamer, a challenge that seemed worthy of his film’s themes.

Fitzcarraldo’s transcendent message and prominent metaphor are what Herzog calls “the helplessness of dreams over the heaviness of reality.” Impassioned by his love for Caruso, the music gives Fitzcarraldo his unflinching resolve. Eerily calm scenes feature Kinski’s mad character on his boat drifting down the river, the jungle’s sounds subdued by piercing records that send Caruso reverberating into the untamed world. Fitzcarraldo’s fixation leaves him blind to the notion that the beauty of Caruso’s voice may not hypnotize the indigenous peoples as it does him. To give up on moving the boat over the mountain, however, would be the equivalent of giving up on Caruso. Likewise, Herzog could hardly put into words his need to tell this story, no matter the obstacles and tragedies that awaited him. And long after any other filmmaker would have quit and gone home, Herzog remained immovably dedicated to finishing his film, to actually lifting a 340-ton boat over the mound. This connection between Fitzcarraldo and Herzog stands as the film’s most enduring quality. This degree of unbridled artistic inspiration is matched in Nature by the savage, unforgiving jungle, whose ethereal presence would haunt Herzog’s production.

The troubled shoot has unfortunately eclipsed the power of the film itself, which is tragic, but it’s also critical, as the tumultuous process of shooting Fitzcarraldo calls attention to Herzog’s approach to filmmaking: his use of driven or inspired characters, his unwavering desire to evoke truth by filming on location, and his transcendent obsession with obsession. Les Blank followed Herzog’s highly publicized production to complete the documentary Burden of Dreams, also released in 1982, and more recently, Herzog committed his account of the production to paper with the book Conquest of the Useless, Reflections from the Making of ‘Fitzcarraldo’. The making of the film has been covered to no end because the subject reveals so much about the director that it cannot be ignored, even when attempting to shift focus away from how the film was made. For three years, Herzog labored in pre-production, using that time to find locations and build three identical boats (one to hoist up the mountain, one for river shots, and one to send crashing down the Pongo das Mortes). The earliest steps in the production were financed from Herzog’s own money, as the director knew that no sane investor would bankroll such a dangerous project; the investors came later, after Herzog had already set the film into motion, when putting in funds seemed less risky.

When he first arrived in South America, Herzog found himself in the midst of a border war between Ecuador and Peru and an uproar over oil companies building a pipeline through the land of native peoples. He changed locations several times to avoid such local trouble, but the negative media attention followed Herzog’s production wherever he went. The spot Herzog picked was isolated, 500 miles from any major city, though he fully admits the film could have been shot just outside Ecuador’s capital, Quito. Isolation added to the truth of his picture. By the time nearly half the film was in the can, the version he had been shooting was doomed. Jason Robards was originally cast as Fitzcarraldo, but the actor became ill with amoebic dysentery; his doctor forbade him from returning to the set. The delay to find a new leading man also overextended the contract of costar Mick Jagger, whose obligation to a Rolling Stones tour prevented him from completing his role as Fitzcarraldo’s mentally deficient associate. Jagger’s name and talent were so irreplaceable that Herzog chose to write the character out of the script, as opposed to finding a replacement. As for the principal role, Herzog considered playing the part himself, and while that may have been one of the great self-reflective performances ever put to screen (imagine if Federico Fellini chose to star in 8 ½), Herzog could hardly capture the lunacy behind the eyes of his frequent leading man, Klaus Kinski.

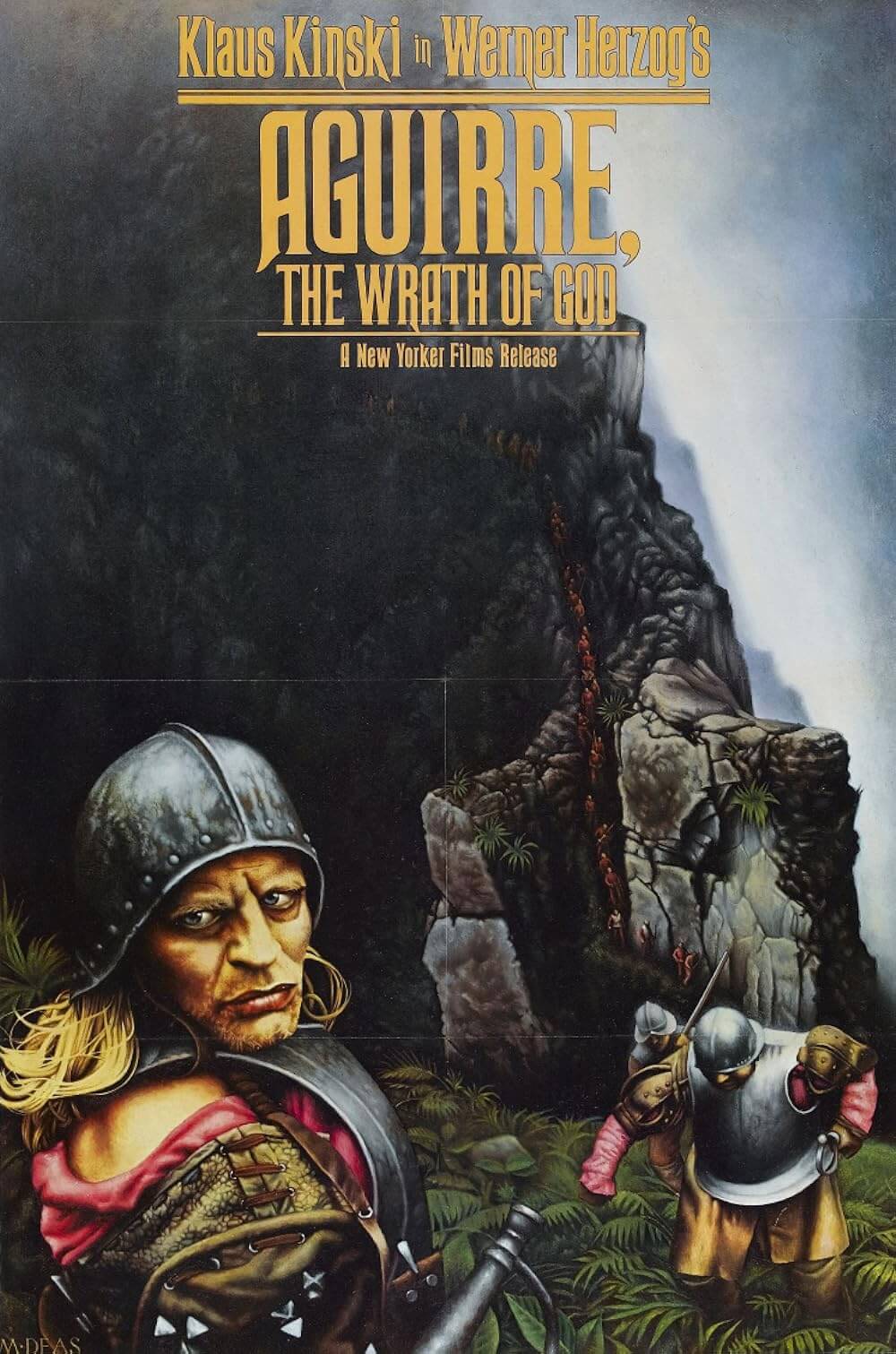

Kinski had starred in Herzog’s Aguirre, The Wrath of God in 1972, another production fraught with troubles, shot on location in Peru, and another character by Kinski whose obsessions were pitted against a cruel Nature. The actor, who had appeared in well over 100 films by the time Herzog discovered him, had a history of mental illness (in the 1950s he was committed for schizophrenia). On the set of Fitzcarraldo, he was known for his raving outbursts and hair-trigger temper, a characteristic enhanced by the sweltering heat and isolation of the Amazon jungle. Then quiet and physically restrained indigenous tribes Herzog had hired to act and assist in the production thought Kinski’s shouting and physicality were offensive. Kinski became so intolerable that one of the native chiefs offered to slay Kinski for Herzog, but Herzog declined the considerate offer. Tolerating Kinski’s conduct became necessary given the resultant performance; he was an actor burning with emotion in his expressions, with an evident madness in his eyes, which was something Robards could have never accomplished. In all, the actor and director would make five films together, and in 1999, Herzog paid tribute to their volatile working partnership and friendship with the documentary My Best Fiend: Klaus Kinski.

Whereas Kinski’s presence had almost ruined the filming of Aguirre, The Wrath of God, Nature, and Herzog’s unflinching determination to finish production were the far more dangerous elements on Fitzcarraldo. To move his massive vessel over the mountain deep in the Peruvian jungle, Herzog commissioned 700 natives to operate a pulley system. The Brazilian engineer hired to design the system walked away from the project when Herzog opted to continue, after he was told there was a 70% chance the cables would break and injure workers. An industrial tractor helped ease the pressure on the pulleys, but when it broke down, production was halted until the parts ordered from Miami arrived weeks later, only to have the crew discover the wrong parts had been sent. When the tractor was working, the knee-deep mud prevented anything from functioning properly. After months of preparation, the tractor would slip, the pulleys would loosen, and the boat would slide back down the hill. Herzog blamed Nature. By the end of the shoot, he felt the jungle was an evil place, or perhaps that “civilized” humanity was simply too naïve to exist in this environment. In Burden of Dreams, he says the jungle is “vile and base” and “a land which God, if he exists, has created in anger.”

The production’s nightmare stories go on and on: In a rage, one of the crew burned down Herzog’s house; when he was wounded by a potentially fatal snake bite, another crewmember saved his own life by quickly chopping off his leg; due to a drought, the aggressive native Amahuaca tribe were forced downriver, closer to the production, and they attacked by shooting arrows into the crew’s camp. Still, no one died as a direct result of Herzog’s decisions or fervent control over the production, even if the exaggerated horror stories claimed he was torturing his cast and crew. Activists and members of the press opposed to the production were even harsher on Herzog than he was on himself, often because they believed he was harming the purity of the land and native tribes. Before shooting ever began, they attempted to link him to the military so he might be viewed as an enemy to the locals. A French political activist showed tribespeople photos of Auschwitz victims and claimed that Herzog was responsible and that all German people behaved in such ways. Back in Germany, a tribunal was formed to determine if Herzog was torturing or enslaving the local tribes. Fortunately, Herzog took special care to provide as much as he could, offering campgrounds, doctors, and pay to his workers. He especially prides himself on how, after all, the years since shooting the film, not even the jungle land he cleared of trees for the shoot shows that his production was there, as any wound he left on the terrain has since healed. These reports of abuses toward the natives, even a fantastical rumor about Cardinale being hit by a car, came about because Iquitos was, ostensibly, in the middle of nowhere, which meant no accurate press coverage could get in or out. All conceptions of Herzog’s production were left to often negative speculation.

When the film was released, Herzog won the best director award for Fitzcarraldo at the 1982 Cannes Film Festival. His career thereafter would take an auteuristic path that seems forged by the trauma of shooting the film. Though earlier examples, such as Aguirre, The Wrath of God, explore the theme of humanity’s arrogance falling before a pitiless Nature, both on and off-screen, Fitzcarraldo represents a singular example of Herzog’s determination to endure in the face of anything put before him. And his subsequent work feels focused because of it. Consider when Robards and Jagger had both been forced to leave the production of Fitzcarraldo, and Herzog was at his lowest point. Another director would have given up, having invested so much money and time in a film that was canceled when nearly half-complete. Instead, Herzog went off to Europe to secure investors who thought him foolish for not quitting altogether. But this director has dreams, and his passion is to pursue them. To those who called him mad, he said, “I live my life, or I end my life with this project”, which is the director’s approach to each new project. At the end of the film, we know Fitzcarraldo will find a new project or obsession despite his failure, just as we know that Herzog will carry on through any delay or obstruction and continue making films. Indeed, only five years after Fitzcarraldo, Herzog did not waver from his experiences with either Nature or Kinski—he teamed with Kinski again for their final collaboration on Cobra Verde (1987), another distressed production shot on location in Ghana.

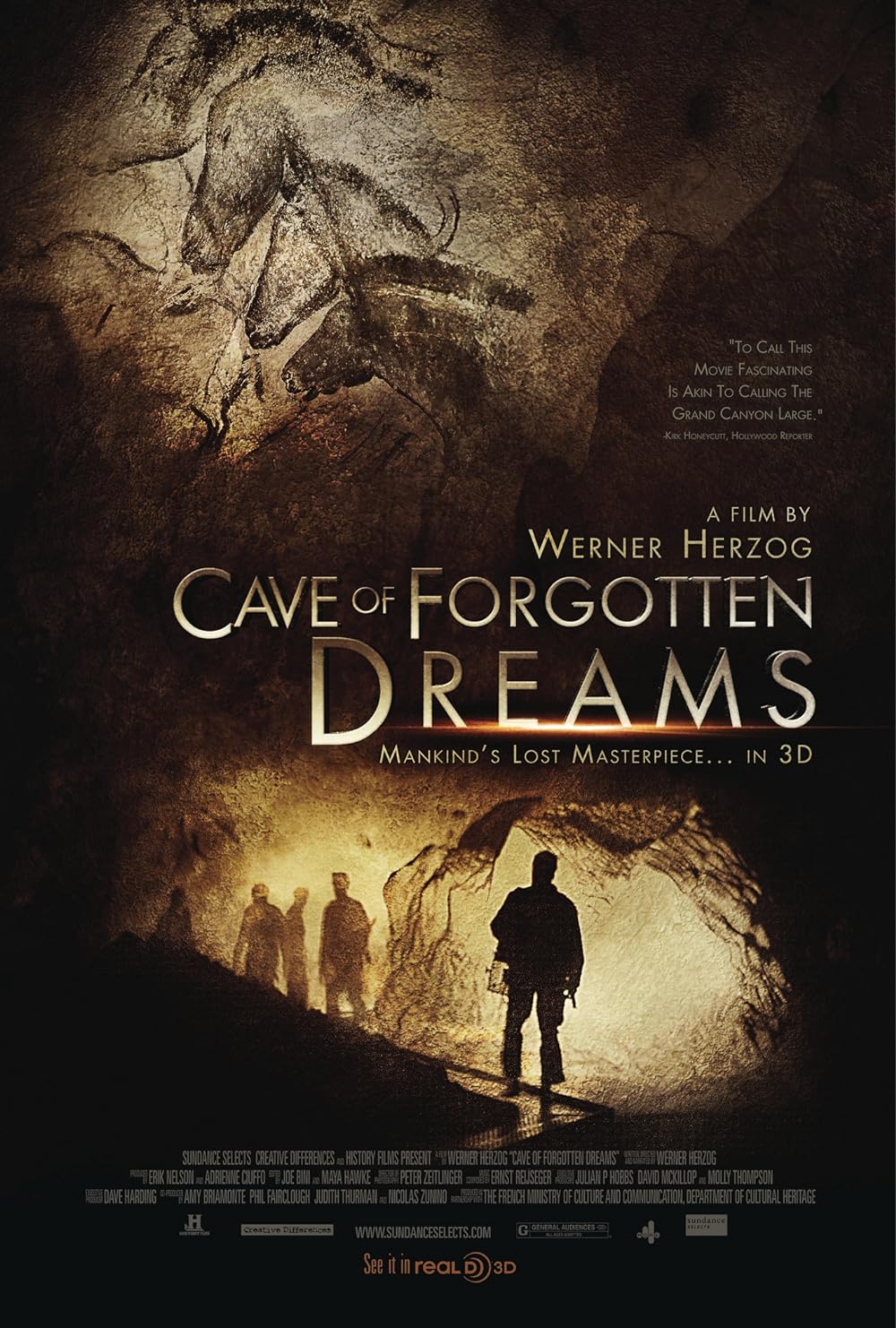

In his fiction films and documentaries (two methods Herzog does not view as different), his subjects, much like Fitzcarraldo and Herzog, are people driven into desolate, unforgiving landscapes to satisfy an inner obsession. His documentary The White Diamond (2004) follows Dr. Graham Dorrington’s dangerous attempt to capture images of Kaieteur Falls in the heart of Guyana on an impractical flying ship. Later, Herzog made Grizzly Man (2005), an account of unstable activist Timothy Treadwell’s travels to the Alaskan wilderness to live with grizzly bears, a venture that proves a fatally arrogant temptation of Nature. Other Herzog films rearrange this conflict, but still include the elemental components of humanity, obsession, and Nature. In the case of Dieter Dengler, as depicted in Herzog’s documentary Little Dieter Needs to Fly (1997) and his drama on the story, Rescue Dawn (2006), the director considers a man forced into a harsh setting when he finds himself in a Vietnamese prison camp. When he escapes, the resulting encounter with Nature leaves emotional scars that have since shaped his lifestyle; here, Herzog’s intent is not obsession, but the spiritual disfigurement that occurs from Dengler’s exposure to the Vietnamese jungle. In 2009, Herzog released The Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call: New Orleans, a twisted tale of a cop who, after being injured during Hurricane Katrina, spirals into a drug-addicted, corrupt monster mirroring the broken city around him. With each case, Herzog examines humanity’s relationship with Nature, its influence over us, and our perpetual desire to conquer it.

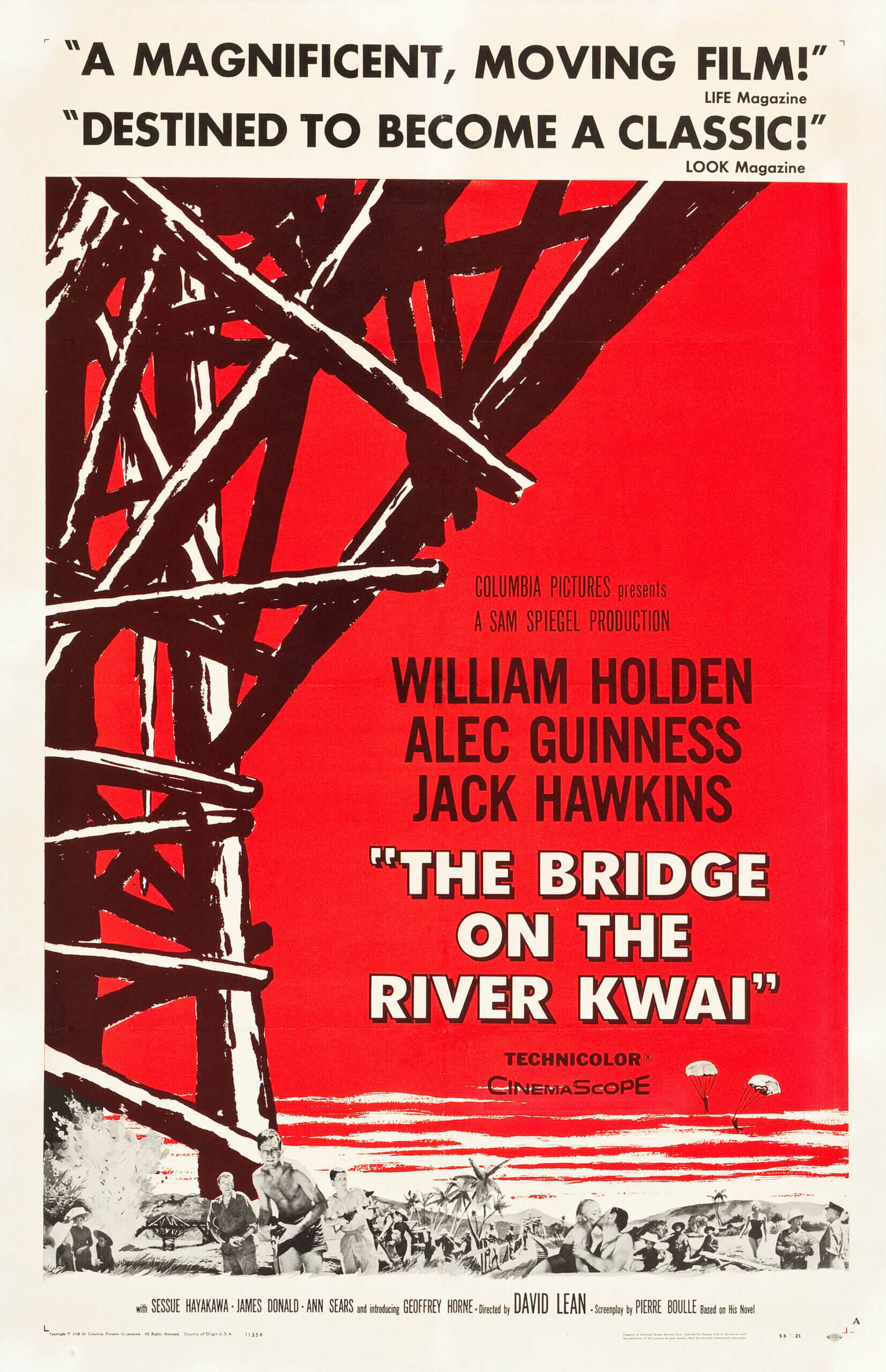

Despite forces that seemed to accumulate against him, Herzog was devoted to the ferocious purity of his art and refused to give up on Fitzcarraldo. His steamer eventually made it over the hill, and he soon acknowledged that no one would ever need to duplicate such a feat—there were much easier ways of accomplishing this task (as Carlos Fermín Fitzcarrald proved), but few would be so cinematically beautiful. Herzog’s triumph earned him the self-designated nickname “Conquistador of the Useless”. And though his project offers no functional purpose, the film remains as Herzog described it, a “great metaphor” whose metanymic reasoning not even Herzog can articulate. Nevertheless, both he and his audience understand the profundity of what appears onscreen. With Fitzcarraldo, the director considers the fate of a dreamer against a chaotic Nature, and for that reason, seeing Kinski’s character as a manifestation of Herzog becomes a result of understanding the director’s undeniable personal presence in this film. Here, he draws a parallel between story and director that occurs only with the boldest and most daring filmmakers, such as Federico Fellini’s 8 ½ (1963) or Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985). Embedded into the essence of such visionaries is a tendency to project themselves into their work. Herzog’s picture, in turn, becomes an exploration of the limitless nature of artistic obsession. Wrought by the same fixated qualities of his film’s title character, Herzog depicts himself within Fitzcarraldo and, in doing so, proclaims his sometimes mad dedication to his craft.

Bibliography:

Cronin, Paul. Herzog on Herzog. London: Faber and Faber Ltd., 2002.

Herzog, Werner. Fitzcarraldo: The Original Story. Fjord Pr; 1st Edition, 1983.

Herzog, Werner. Conquest of the Useless: Reflections from the Making of ‘Fitzcarraldo’. Ecco, Reprint Edition, 2010.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review