Dracula

By Brian Eggert |

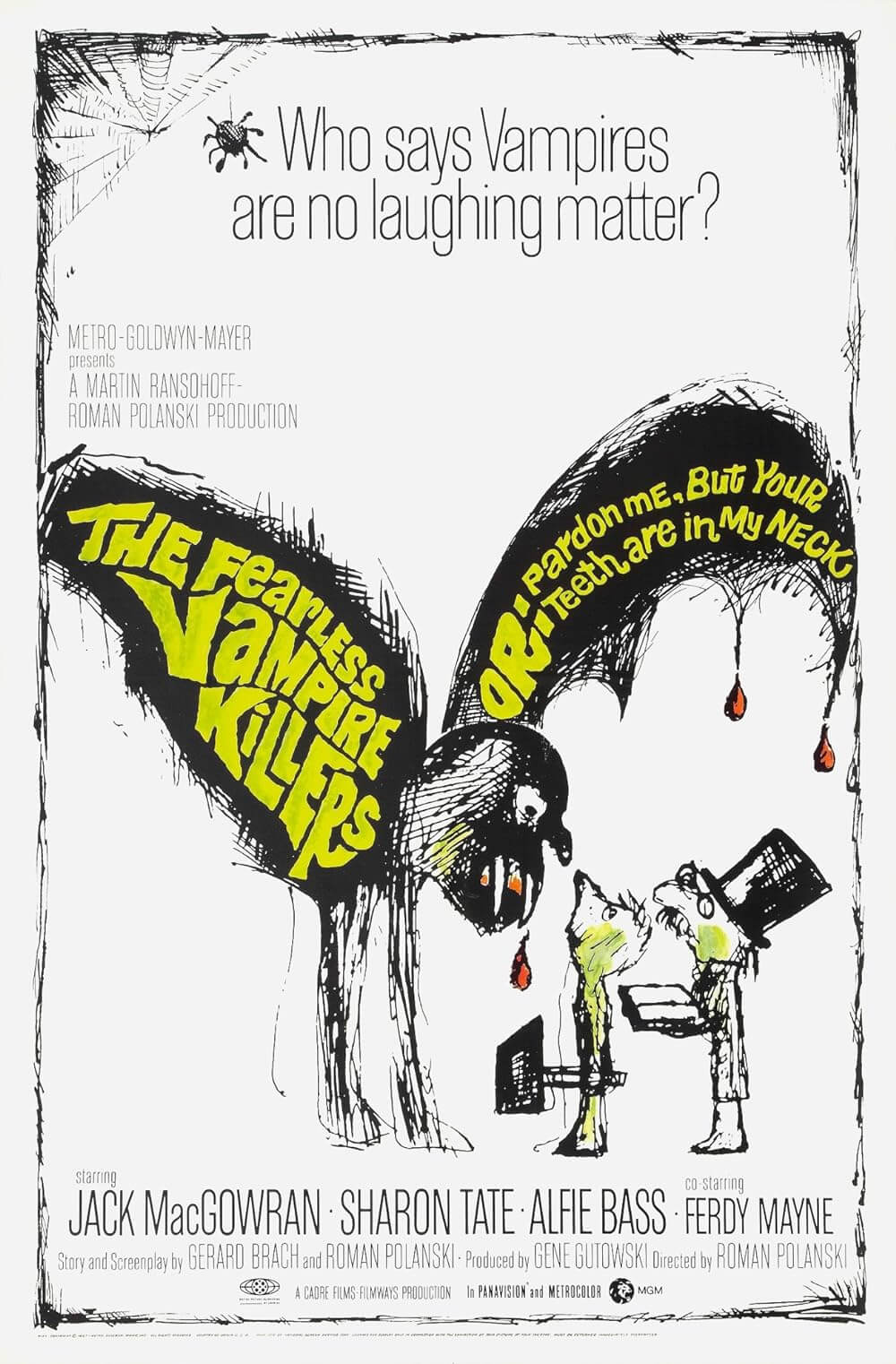

Late in Luc Besson’s Dracula, Romanian soldiers enter the Count’s castle for a climactic fight with the vampire’s bodyguards: a group of dwarfish stone gargoyles rendered in subpar CGI, looking like rejected concepts from a Disney live-action remake. Watching this, I couldn’t help but laugh at their absurdity. And it wasn’t the first time I chuckled during Besson’s movie, a splashy production made outside of Hollywood by the French director’s production company, funded by European investors, and released in some markets as Dracula: A Love Tale. At other points, I groaned in amusement at the film’s tonal incongruity between self-seriousness and outright silliness. Besson attempts to tell Bram Stoker’s gothic horror story with a stated focus on the love story over horror thrills, but that’s been done before, and better, and without Dracula having cutesy stone sidekicks. But the cartoony gargoyles are just one example. Besson makes one baffling choice after another in his blatantly derivative yet quirky English-language production, which might as well be called Luc Besson’s Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

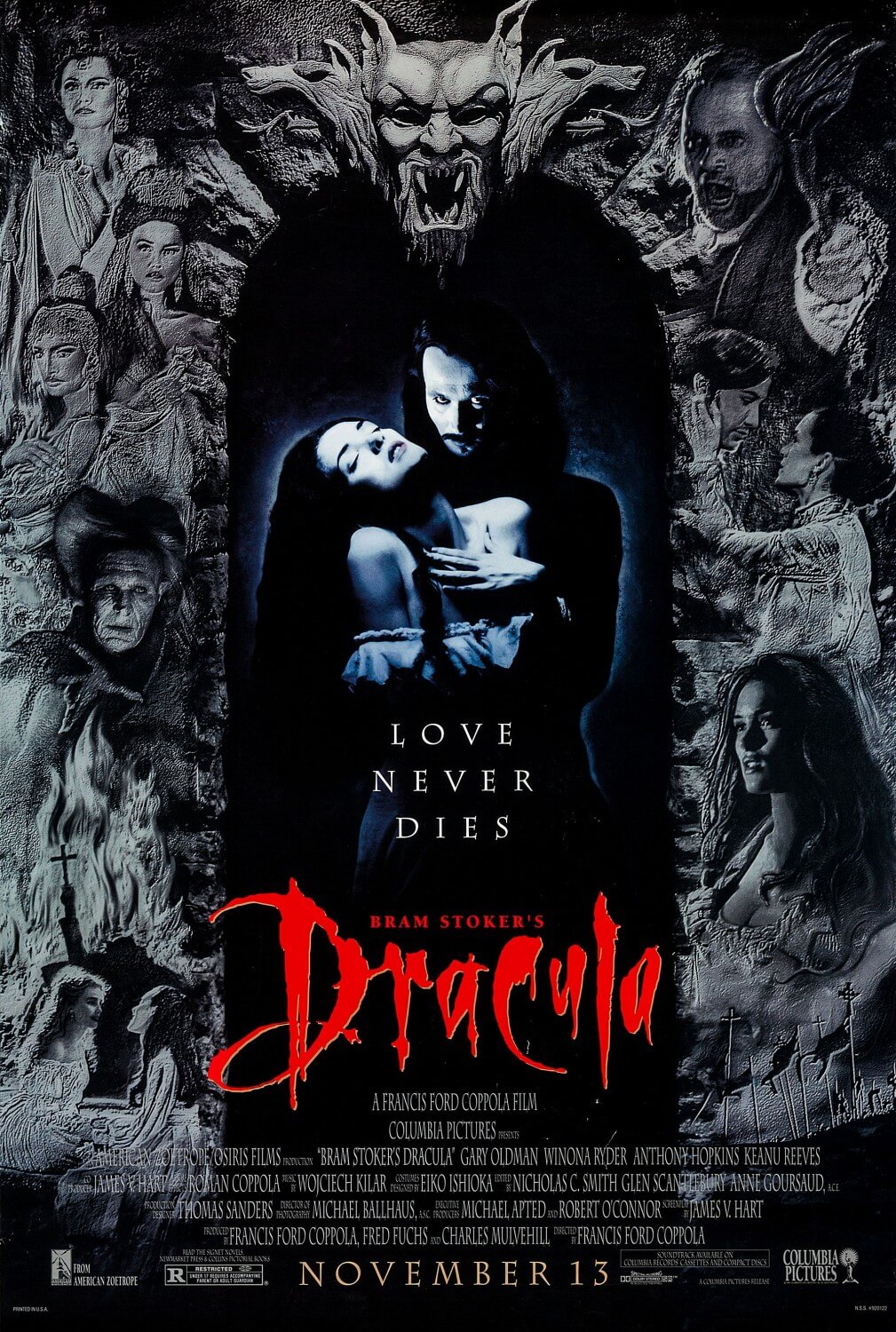

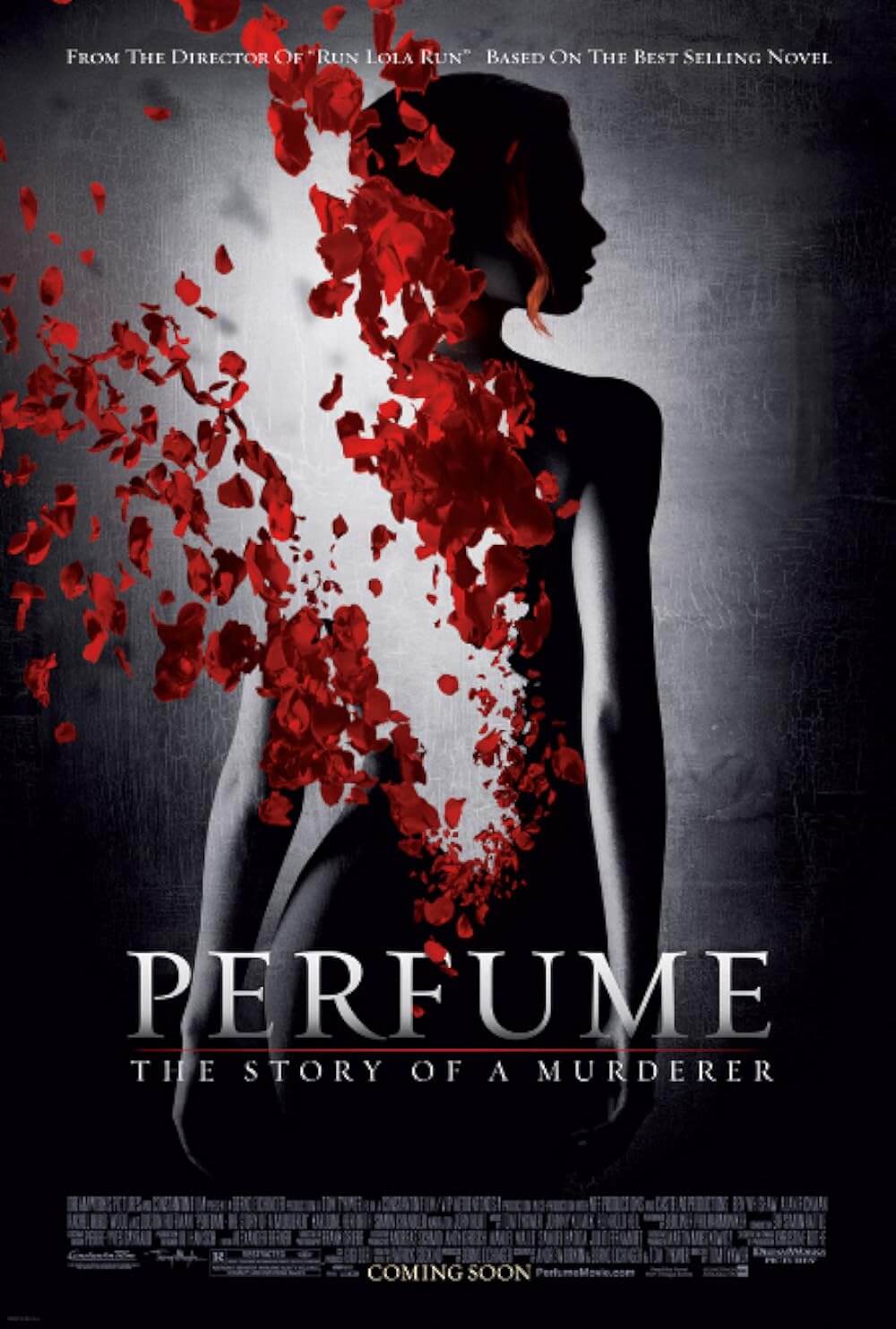

To be sure, Besson’s main influence is unmistakably Coppola’s operatic, sensationalist production from 1992, a technical wonder that earned multiple Oscars for its bravura craft. At times, Besson replicates whole images and compositions from Coppola’s film, an approach that feels less like a loving homage than shameless pilfering. Black silhouettes against a crimson sky, a vampire hissing at a crucifix until it burns, and a leathery white Dracula dying in his lover’s arms—Besson copies these iconic shots from Coppola’s work. But he doesn’t stop there. A subplot in which Dracula becomes a perfumer to create a hypnotic fragrance draws on Perfume: The Story of a Murderer (2006), and another sequence finds Besson dabbling in nunsploitation when Dracula brings a convent into an ecstasy worthy of The Devils (1971). It’s all too familiar, and what little originality Besson adds to the mix proves oddly goofy and uninspired. Usually an action movie director, Besson has never made a horror movie or a period drama, and it shows.

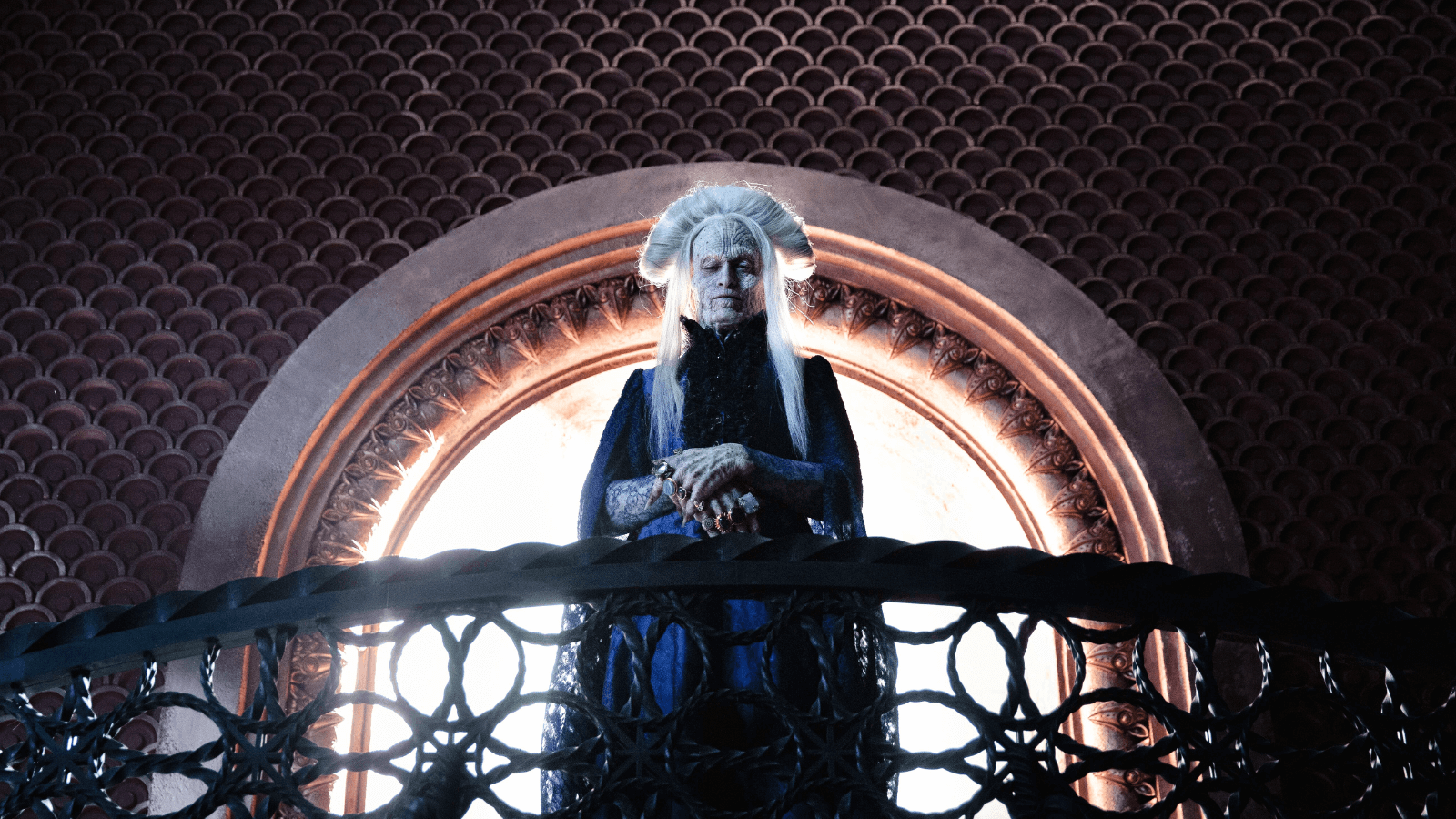

The project developed out of Besson’s desire to work with Caleb Landry Jones again after their 2023 collaboration on DogMan. The writer-director felt the actor’s uncanny screen presence suited Count Dracula. At the very least, Jones seems to be having fun behind loads of practical iguana-necked makeup and wigs. Still, he’s no charismatic Romanian prince, nor do the other performers disappear into their roles. Jones’ Dracula first appears in 1480, with the Romanian prince and his beloved Elizabeta (Zoë Bleu) in a lovers’ montage of pillow fights, copious lovemaking, food fights, and rifle lessons—you know, the usual trappings of the honeymoon period. After the prince goes off to war against the Muslims, he learns that Elizabeta is in danger and races away from the battle to rescue her. But in the fracas, Dracula commits a big whoopsie and accidentally kills her. In the throes of grief, he renounces God until he’s reunited with Elizabeta, rendering him immortal. And for the next 400 years, Dracula feeds on the European royal class, moving from country to country and brainwashing them with a mesmeric perfume he invented.

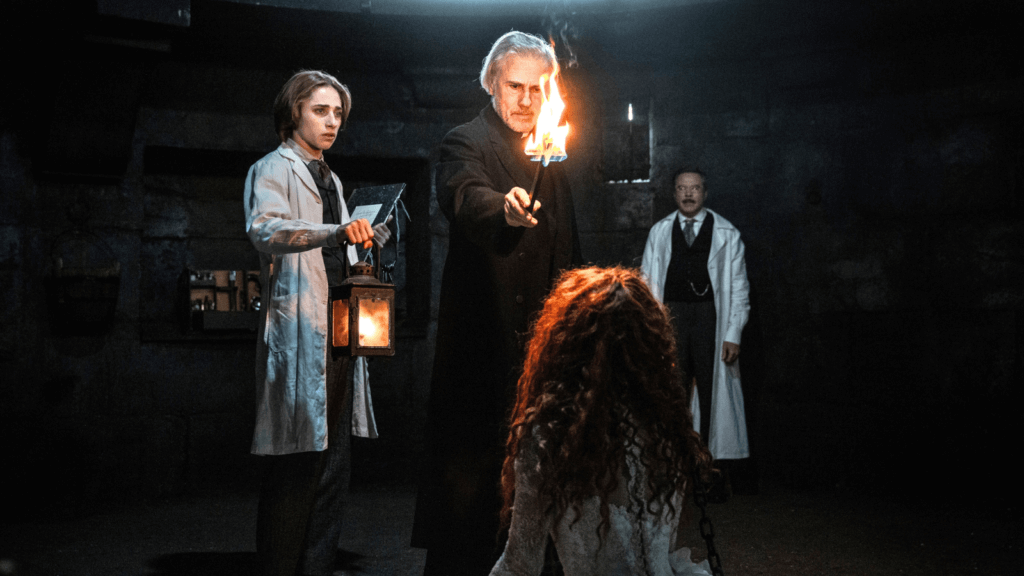

Meanwhile, in Paris around 1880, a priest (Christoph Waltz) claims to approach vampire-hunting like a modern criminal investigation, relying on observation and evidence, but nothing much comes of it. A doctor, Dumont (Guillaume de Tonquédec), enlists the priest to examine Maria (Matilda De Angelis), a patient with fangs and bloodlust. De Angelis gives a ridiculous, teeth-chattering, tongue-wagging performance that goes beyond mere overacting and enters into camp. So do scenes with Jonathan Harker (Ewens Abid), the doltish real estate agent who brokers a deal at Dracula’s castle and thinks his new client’s telekinesis is a cute trick. Soon enough, Harker finds himself trapped by CGI gargoyles, who behave like the flying monkeys in The Wizard of Oz (1939). Dracula eventually arrives in Paris to find Harker’s fiancée, Mina (also Bleu), a dead ringer for Elizabeta, and reclaim his centuries-dead lover. The story plays out predictably, following Stoker’s text and much of Coppola’s visualization.

Unfolding at a watch-checking pace with tedious narrative familiarity, Besson’s Dracula alternates between admirable production values and downright embarrassing flourishes, recalling his disastrous epic The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc (1999). On the surface, the director’s longtime production designer, Hugues Tissandier, shoots in stunning locations, ornamented with lavish costumes by Corinne Bruand and impressive prosthetic effects on the titular vampire (by makeup artists Julia Floch-Carbonel, Jean-Christophe Spadaccini, and Denis Gastou). Colin Wandersman’s crisp cinematography and Danny Elfman’s very Danny Elfman score give way to an imbalance of unconvincing CGI creatures, digital backgrounds, and kitschy editing. Indeed, the production is offset by its quirky sense of humor, with antics ranging from rambunctious gargoyles to a slapstick decapitation. Much of Dracula feels like a tonal mess, and not a single moment lands as intended. I spent the entire time feeling at a remove, outside of the story, like watching a train derailment in real time, the railcars flying off the tracks and piling onto one another in a horrible spectacle.

Great stories last because they lend themselves to reinterpretation by artists who rethink them for new generations. Why else have countless Shakespeare adaptations, each told from a new perspective, appeared on film and stage? Dracula must be one of the most frequently adapted stories of the last century, reconsidered every few years with a new style, angle, or theme, often emphasizing varied contemporary or aesthetic concerns. For instance, in 2024, Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu supplied a remake of a silent film based on Stoker’s text, and last year, Radu Jude’s unconventional take on Dracula tackled AI and the treatment of the Dracula myth by the Western world. But Besson brings nothing new to the story that others haven’t done better, and his focus on the love story feels underdeveloped next to his various tangents and stylistic asides. His additions prove both ludicrous and uninventive, despite how aesthetically pleasing the costumes and settings might look. The new iteration may even feel absurdist compared to Coppola’s version or Eggers’ dour film, offering no real scares or romantic yearning. Running more than two hours, Besson’s tedious version of Dracula feels like an expensive, reiterative piece of filmmaking without a single note of inspiration or originality.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review