Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die

By Brian Eggert |

Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die opens with Sam Rockwell bursting into Norm’s Diner one night. Unkempt and draped in plastic sheets, tubes, wires, and gizmos, he looks like a homeless man who modeled his wardrobe on Bruce Willis’ time-travel getup in 12 Monkeys (1995). It’s an appropriate look for a guy who claims to be from the future, where a malignant artificial intelligence has dominated humanity. “All of this goes horribly wrong,” he declares to the diner’s patrons, holding what he claims to be a triggering mechanism to a bomb strapped around his torso. People were too wrapped up in their smartphones, social media, and uncritical thinking to notice the AI takeover; now they’re sedentary wastrels who survive on feeding tubes. With a madcap energy that recalls Rockwell’s performance as Zaphod Beeblebrox in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (2005), his character asks for volunteers to stop the inventor of this AI. From there, it only becomes another increasingly weird, thoroughly entertaining, and predictably existential feature directed by Gore Verbinski.

Returning after nearly a decade without releasing a new film, Verbinski makes a welcome escape from director’s jail following two financial disappointments in a row: The Lone Ranger (2013) and A Cure for Wellness (2016). These trailed an impressive run of blockbusters ranging from The Ring (2002) to the first three installments of the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise to the superb animated feature Rango (2011). Verbinski’s fall from Hollywood’s grace coincided with his increased aversion to conventional narratives. Though his risk-taking hasn’t always paid off in box-office receipts and studio profits, it has resulted in some fascinatingly obscure movies, Rango and The Lone Ranger above all. That tendency registers as a gamble for risk-averse executives who are less concerned with art than exploiting intellectual property for everything it’s worth. The thing is, Verbinski has always been a zany stylist with a brash sense of showmanship and a penchant for existential crises. But when his proclivities stopped paying off, he was blamed.

It’s no surprise that Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die wasn’t put into theaters by one of Verbinski’s past studio affiliations, such as Disney, DreamWorks, or Paramount. Instead, the film was released by the smaller Briarcliff Entertainment, a distributor known for investing in dicey projects bound to court controversy. They put out the Jamal Khashoggi documentary The Dissident (2020) and the Donald Trump biopic The Apprentice (2024) when no one else would. Briarcliff balances its more precarious titles with a stable of sure things, including a swath of Gerard Butler and Liam Neeson actioners. For Verbinski’s film, Briarcliff risks alienating those in the entertainment industry who have embraced AI as a cost-cutting tool across various stages of production. But refreshingly, Verbinski and screenwriter Matthew Robinson (The Invention of Lying, 2009) have no problem suggesting that AI and an overreliance on technology threaten to destroy what makes us human.

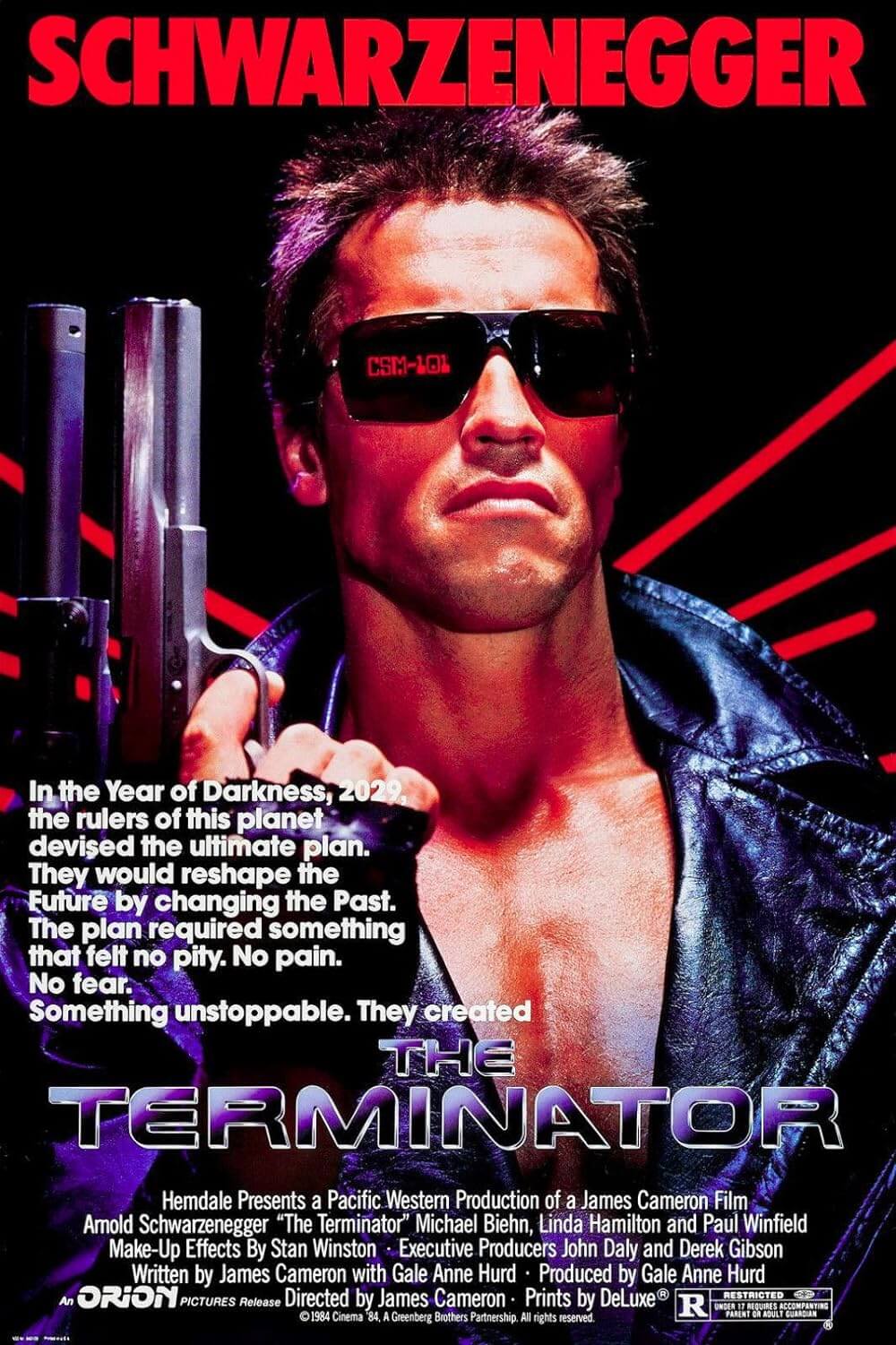

Borrowing the conceptual framework of The Terminator (1984) and its 1991 sequel, Verbinski’s time-travel scenario has a simple endgame. Rockwell’s unnamed character wants to stop the future’s AI overload by installing protective software to limit its powers before its creator, a nine-year-old boy, writes the code. That rather straightforward setup zigs and zags and turns upside-down, however. He explains to the greasy spoon’s guests that he has attempted this mission 117 times, bringing along different combinations of these people each time. For the skeptics, he shares details about their lives he couldn’t otherwise know. That’s enough to convince several volunteers. Among them, there’s Susan (Juno Temple), a mousy, quiet woman at the back; Janet and Mark (Zazie Beetz, Michael Peña), a pair of high-school teachers hesitant to admit they’re in love; and Ingrid (Haley Lu Richardson), a young woman with faded blue hair, a tattered dress, and an allergy to Wi-Fi. As the film progresses, flashbacks shed light on these people and why they join the time-traveler’s quixotic quest.

In another universe, Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die would have been a limited or even ongoing series that spends each episode exploring Rockwell’s cohorts. Instead, it’s the kind of jam-packed cinema that feels like Verbinski channeling Terry Gilliam by way of Douglas Adams. Each character’s backstory offers a look at how technology has robbed humanity of something essential, albeit with horror-tinged fantasy elements. In Janet and Mark’s tale, youth culture depends entirely too much on their devices, turning them into veritable zombies whose brains receive orders from their phones. In Ingrid’s chapter, we learn about how her life was derailed when her boyfriend chose virtual reality over her, ostensibly agreeing to live in the Matrix while his physical self resides in a real-world incubator. The darkest yet funniest backstory involves Susan, who lost her son in a school shooting, only to get a cloned replacement—a development recalling the “Common People” episode of Black Mirror. One couple she meets has lost the same child in four different school shootings, and they have resolved to “have fun with it” by experimenting with their clones, making their latest one freakishly tall and Muslim. Sure, why not?

Along the way, several of the other diners perish in horrible ways. The police and a couple of goons in pig masks hunt the time-traveler. And just when they reach the house in the suburbs where their target lives, they’ll face an unpredictable threat conjured by the AI. The movie openly references Ghostbusters (1984), where the ultimate evil—a Stay-Puft Marshmallow Man—becomes a reality because one of them imagined it. Here, the result is far more surreal, hilarious, and bafflingly strange: a giraffe-necked cat with hooves and a glitter-spraying penis. The effect looks a little silly, but it’s no less admirably obscure. The film’s wonderful impulsive energy continues in the climactic sequence, laden with demented toys and a tornado of wires that ultimately becomes a tad overblown and expositional, if also inspired for its out-there ideas and execution. Verbinski’s satiric edge is only matched by his showmanship, with cinematographer James Whitaker and editor Craig Wood carefully organizing the film’s chaos.

While it’s easy to get lost in Robinson’s kooky assortment of characters and bizarro situations—charmingly performed by a likable cast that’s clearly down with the message—the material’s hypertextuality draws on various films and video games for inspiration. Each allusion underscores how virtual worlds are replacing reality, while AI is gradually chipping away at actual intelligence. After all, why waste time and effort overcoming obstacles, struggling to grow as a person, and improving oneself when, in a virtual environment, your ideal life can be curated and simulated for you? Verbinski and Robinson worry that humanity’s embrace of these technology-driven alternatives—that secret weapon tech bros and billionaires claim we cannot live without, which conveniently allows them to build wealth and seize power—will render reality obsolete, or at least obscure the boundary enough so that simulation theorists will feel validated.

Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die feels like the kind of movie that might never have been made if not for Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022) winning seven Oscars. It has a similar flavor of high-concept sci-fi comedy, though it’s far more cynical about humanity’s prospects. Ideally, moviegoers will see this on the big screen, as opposed to their television, laptop, or phone. Those smaller screens remain the target of Verbinski’s production, which distinguishes its presence on a large-format screen as cinematic art. Its healthy mistrust of AI isn’t just an anti-tech argument, however; the film also acknowledges that AI takes everything about humanity and creates nothing new, presenting us with a “twisted, warped reflection.” The film hopes that, rather than conceding to technology that synthesizes a lazy interpretation and distillation of humanity, people will continue to define themselves in a never-ending battle of self-discovery. It boasts lofty ambitions for a zany, mind-bending comedy, and it’s all the more noble and satisfying for the inspired result.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review