Ella McCay

By Brian Eggert |

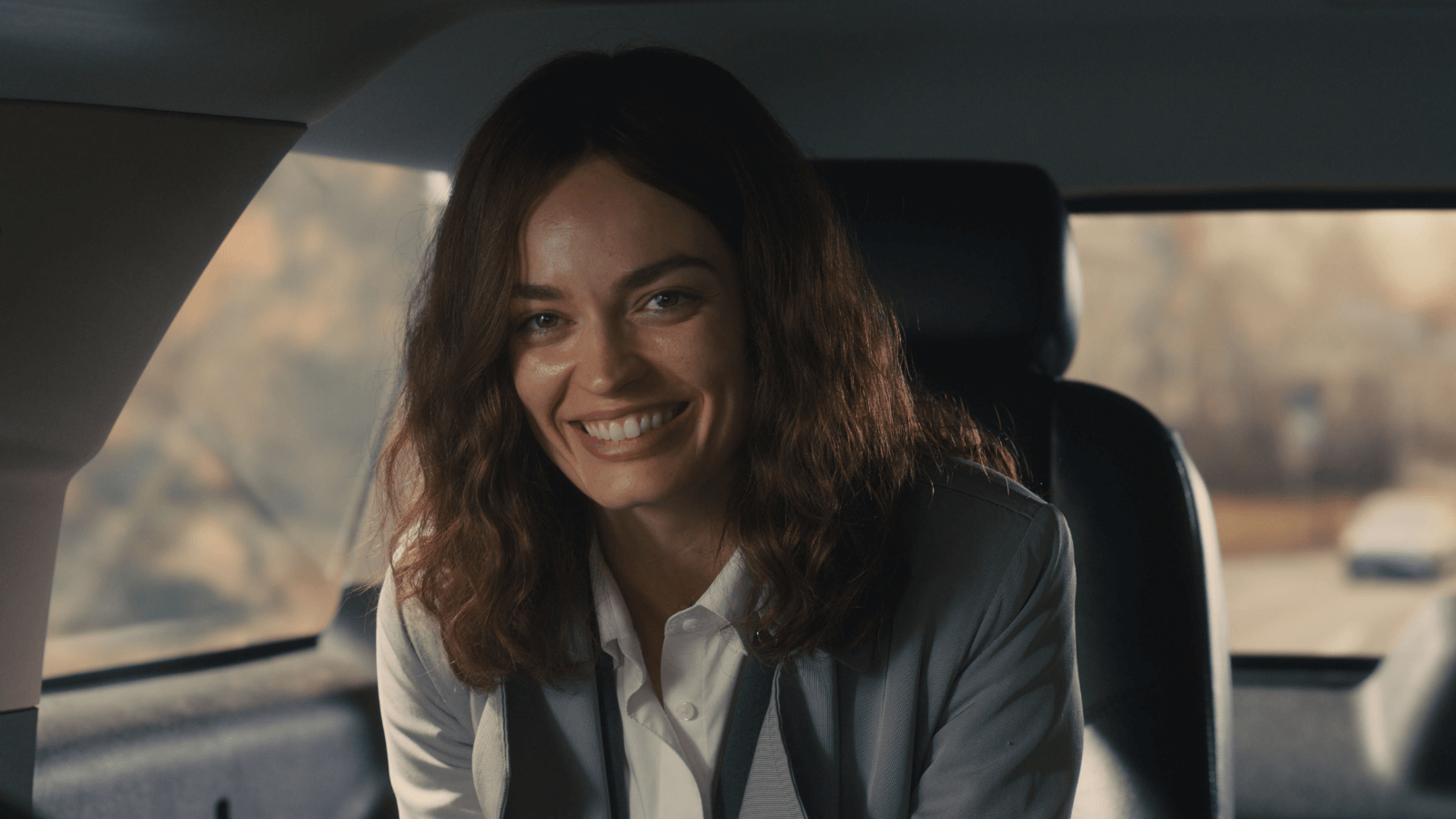

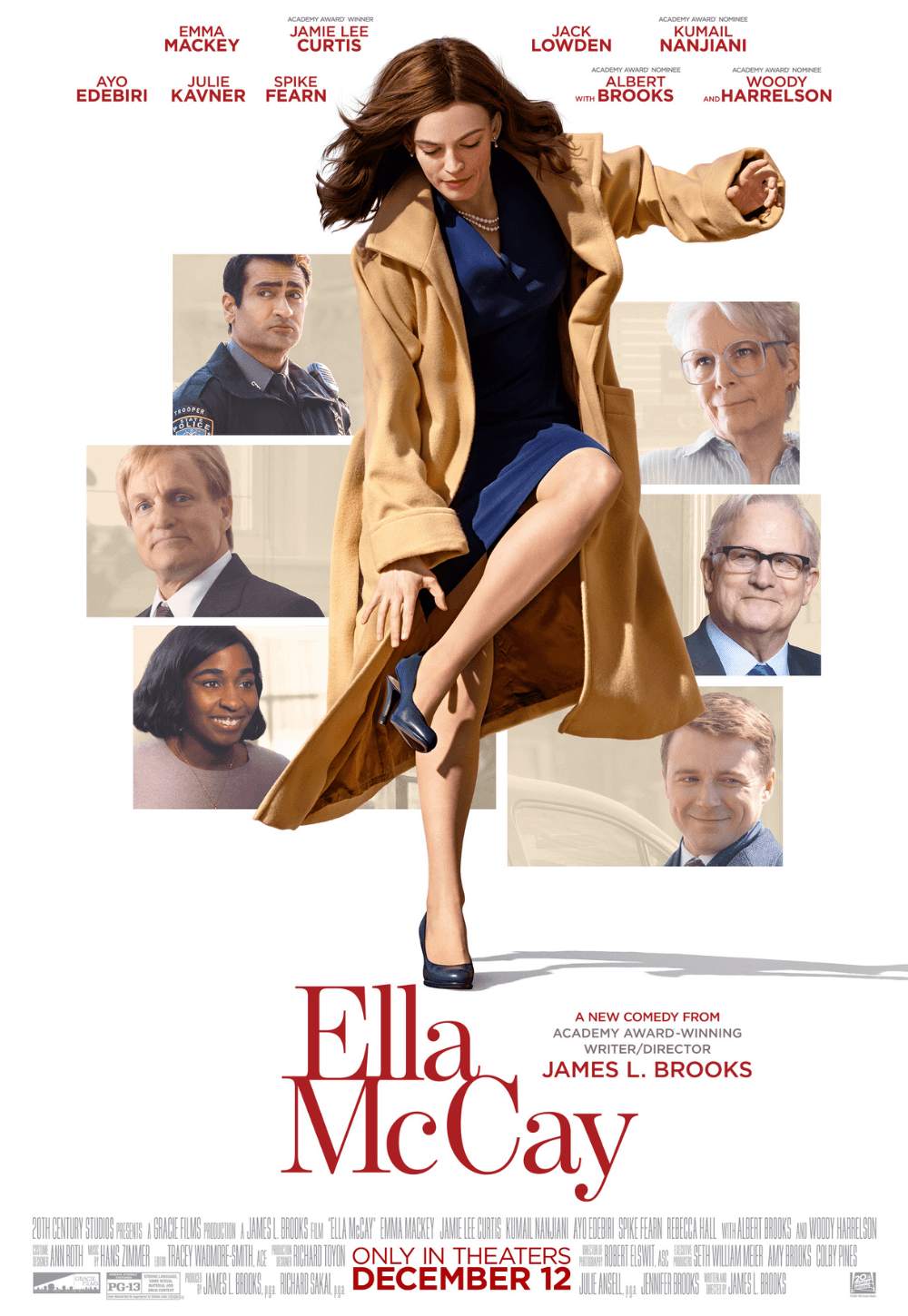

Ella McCay is an amorphous blob of a movie, meandering from one unnatural character and one unconvincing scene to the next. Nothing about this so-called comedy, inspired by screwball classics of yesteryear according to the press notes, delivers as intended. Worse, it plays more like a compressed sitcom than a movie, like Ally McBeal (1997-2002) only less quirky. Emma Mackey headlines an ensemble of likeable performers and funny people such as Jamie Lee Curtis, Ayo Edebiri, Albert Brooks, and Woody Harrelson. But none of them have anything remotely funny or compelling to do. The story just keeps going, and I found myself waiting to be moved or even laugh. However, those reactions never came. Instead, I watched Ella McCay with a sense of bafflement because it was written and directed by the once-great James L. Brooks, who has apparently misplaced whatever magic he once possessed.

Brooks’ name conjures an instant association with quality. He co-created iconic TV shows such as The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Taxi, The Tracey Ullman Show, and the still-chugging-along The Simpsons. His work as a feature film writer-director is just as impressive, with Terms of Endearment (1983) earning him multiple Oscars, Broadcast News (1987) nabbing him multiple Oscar nominations, and As Good as It Gets (1997) receiving both Oscar statues and nominations. Of course, his track record isn’t flawless. The Simpsons hasn’t felt vital for 20 years. And his last two features, Spanglish (2004) and How Do You Know (2010), range from lesser Brooks to absolutely forgettable. So it’s with some regret that I report Ella McCay is Brooks’ worst film to date. The 85-year-old filmmaker has made a flavorless, at times technically wonky effort that feels like a bad imitation of his style.

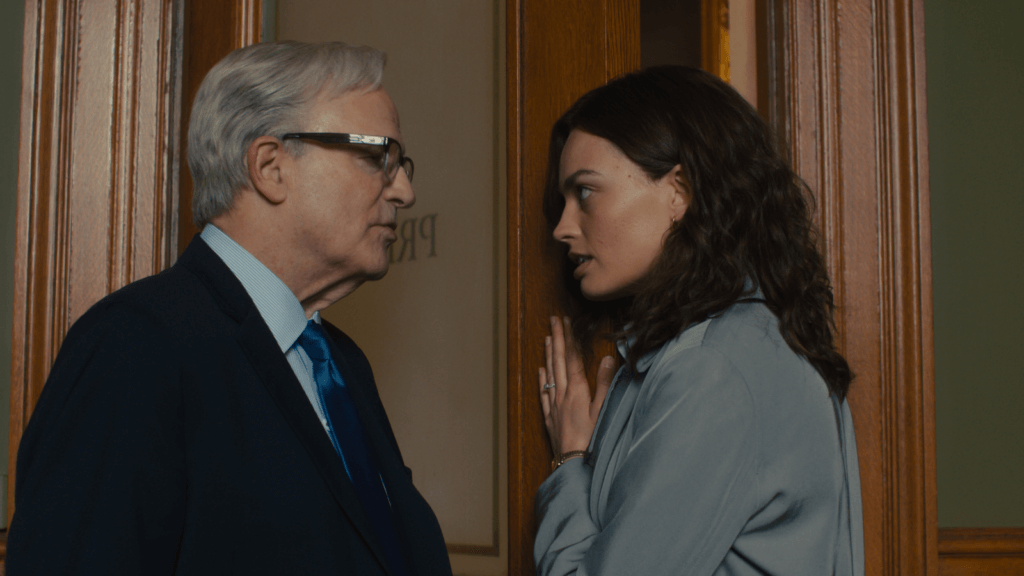

Emma Mackey plays the titular character, who’s less interesting or principled than everyone seems to think. The story takes place in 2008, which, according to Julie Kavner’s narrator, was “a better time when we all still liked each other.” Well, “liked” may be too strong a word, but I get the sentiment. Ella is a 34-year-old lieutenant governor whose mentor, Governor Bill (Albert Brooks), has been promoted, lining her up for the governorship. But she’s concerned about a mild scandal involving her high-school-sweetheart-turned-husband, Ryan (Jack Lowden), whom she has been sleeping with on government property most afternoons to keep their marriage alive. Apparently, that’s illegal. Moreover, Ryan is also a selfish jerk who thinks Ella’s role as governor somehow makes him co-governor, and he expects to be treated as such. Why this intrepid, intelligent woman ever fell for this obviously self-involved asshat is a nagging question, especially given the behavior of his opportunistic mother (Becky Ann Baker).

But Ella falling for a bad guy is an ironic development in her life, as Kavner, who plays her assistant, Estelle, reveals in flashbacks to Ella’s teen years. Ella’s unreliable, womanizing father (Woody Harrelson) was a constant source of disappointment in her life, and little has changed since. Was she so shaken by her father’s infidelity, and the death of her mother (Rebecca Hall), that she failed to see Ryan’s flaws? Elsewhere, Ella yearns to connect with her agoraphobic brother Casey (Spike Fearn), who hopes to reconnect with his former girlfriend (Ayo Edebiri) after he ghosted her a year ago following an awkward proposal. For most of these conflicts, Ella depends on her motherly, stalwart aunt Helen (Jamie Lee Curtis), a rock who always has time and advice for her niece. The story plays out with a brimming optimism that might’ve been a tonic in these grim times; however, it registers as plastic here.

The phoniness of Ella McCay is apparent from the first appearance of the dubious wigs worn by much of the cast. Several characters look off in that respect, especially Mackey, Harrelson, and Brooks. On a purely formal level, Robert Elswit’s cinematography lacks much personality, which, given his superb collaborations with Paul Thomas Anderson, comes as a surprise. The entire picture looks generic and, again, like television used to look at the start of this century. Except that a television show from that era would resolve to be straightforward, calling almost no attention to its form. Brooks and editor Tracey Wadmore-Smith make baffling, abrupt cuts that feel like a desperate attempt to give the material some life. Instead, they make the experience feel disjointed and occasionally confusing. And I barely noticed the recessive score by Hans Zimmer, except for its generally saccharine flavor.

The material is further dampened by its subject matter. In a year marked by political conflicts, watching a comedy set in the world of politics—even in 2008 politics—couldn’t be less appealing. Ella McCay feels like a throwback in all the wrong ways, with Brooks’ unwieldy script lacking the punch, idiosyncrasies, and humanity usually found in his work. All of these characters love and admire Ella, but she never felt real to me in the way Shirley MacLaine and Debra Winger do in Terms of Endearment, Holly Hunter does in Broadcast News, or Helen Hunt does in As Good as It Gets. Much of the fault lies in Mackey’s miscasting. Without that star power or special something that could make Ella compelling, Mackey never brings her to life, whereas one can imagine this being a career-making role for the right performer. But the problems go deeper than the central performance and ultimately reside in the script. On the whole, Ella McCay is a confounding and messy disappointment from a filmmaker who has turned out much better movies.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review