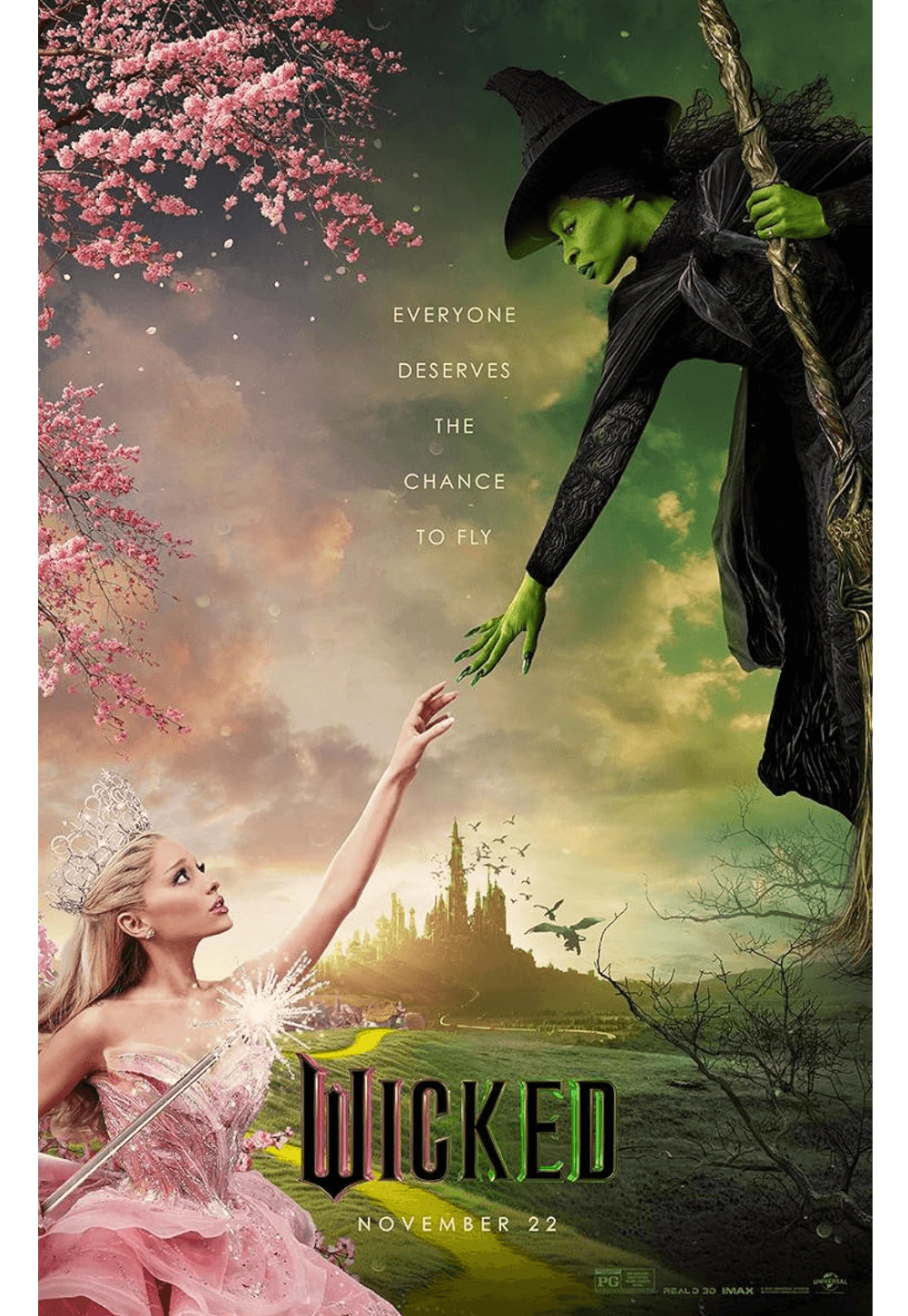

Wicked: For Good

By Brian Eggert |

(Editor’s Note: This review discusses major plot points in Wicked: For Good, including the ending. Best to read it after you see the movie if you care about spoilers.)

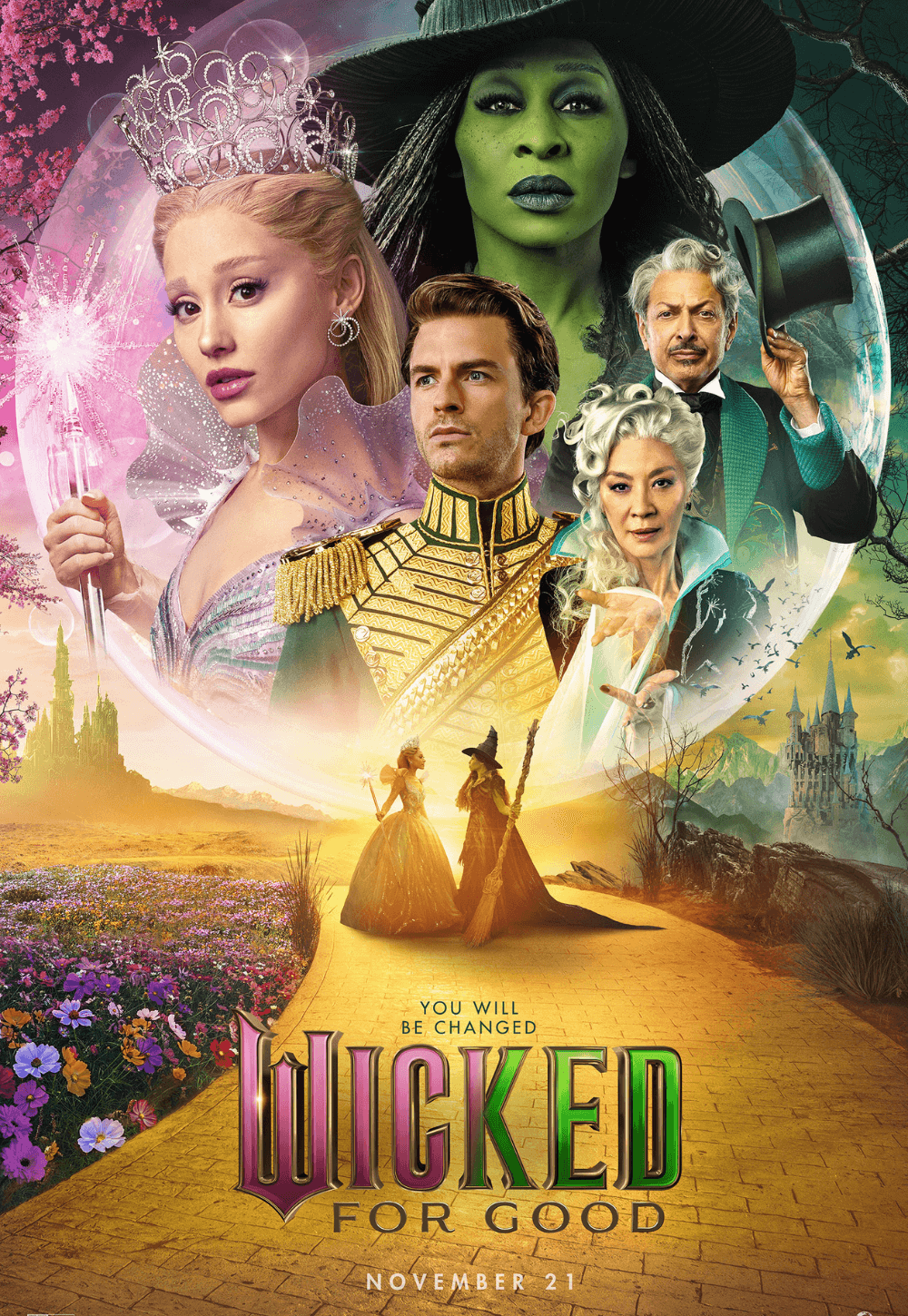

Approaching last year’s Wicked from a neophyte perspective—I have (still) never read Gregory Maguire’s book nor seen the musical by Stephen Schwartz and Winnie Holzman—I was surprised to discover how the story reframes the Great and Powerful Oz as an authoritarian figure in a dystopian fantasy. Oz (Jeff Goldblum, at his Goldblumiest), as we already knew, is a huckster and con artist who pretends to have true magic, despite only having a knack for gizmos. Throughout the 2024 film, he blames his realm’s problems on talking animals. When Elphaba (an excellent Cynthia Erivo) learns of Oz’s duplicity, the Wizard turns her into a pariah, with his propaganda minister and Shiz University headmistress Madame Morrible (Michelle Yeoh) dubbing her the alliterative “Wicked Witch of the West” in fliers, banners, and loudspeaker announcements comparable to those in Nazi Germany. These details resonated with me in this otherwise glitzy Hollywood musical for their parallels to contemporary politics, rising intolerance, and xenophobic scapegoating. And while I was charmed by Erivo’s performance and many other aspects of Wicked, I appreciated its thematic heft and timeliness above all.

Not knowing how the second half of the story plays out—though I could guess most of it, based on the events that occur in 1939’s The Wizard of Oz—I was disappointed to find that Wicked: For Good, the conclusion of Universal Pictures’ cash cow, not only softens its cautionary tale but also feels less vibrant and rebellious. It plays more like an obligatory set of plot points designed to overlap with The Wizard of Oz. Over the prolonged 138-minute runtime, we meet the Cowardly Lion, learn the lovelorn origin story of the Tin Man, discover how the Scarecrow became a living burlap sack full of straw, and see where the pink-strewn and magic-less Glinda (Ariana Grande) got her bubble-mobile and wand. Dorothy and Toto show up too, but in a distracting choice, we see only their backs and silhouettes. Screenwriters Holzman and Dana Fox offer less discovery, wonder, and pluck this time around, leaving audiences with a mostly drab tale that offers little joy or laughter.

But based on the teary eyes and glimmering smiles in my screening, superfans will probably enjoy Wicked: For Good, in part because they know what’s coming, have no doubt experienced this story multiple times on stage, and will delight in seeing a cinematic adaptation. However, I found myself struggling with how the story unfolds and how the events lead to a confounding moral compromise. The sequel opens with the land of Oz in a state of fearmongering and self-glorification, exploiting laborers and animals to build the Yellow Brick Road in the Wizard’s honor. “They’re never going to stop believing in me,” he observes later in a Trumpian remark. “They don’t want to.” Indeed, some Ozians have swallowed the anti-animal disinformation coming out of the Emerald City. But dissenters say, “This is not the Oz I know.” And just like those who fled Hitler’s Germany in the 1930s, the animals of Oz resolve to abandon their homeland rather than risk being placed in cages and rendered voiceless, reasoning, “We can’t stay here […] It’s become rotten.”

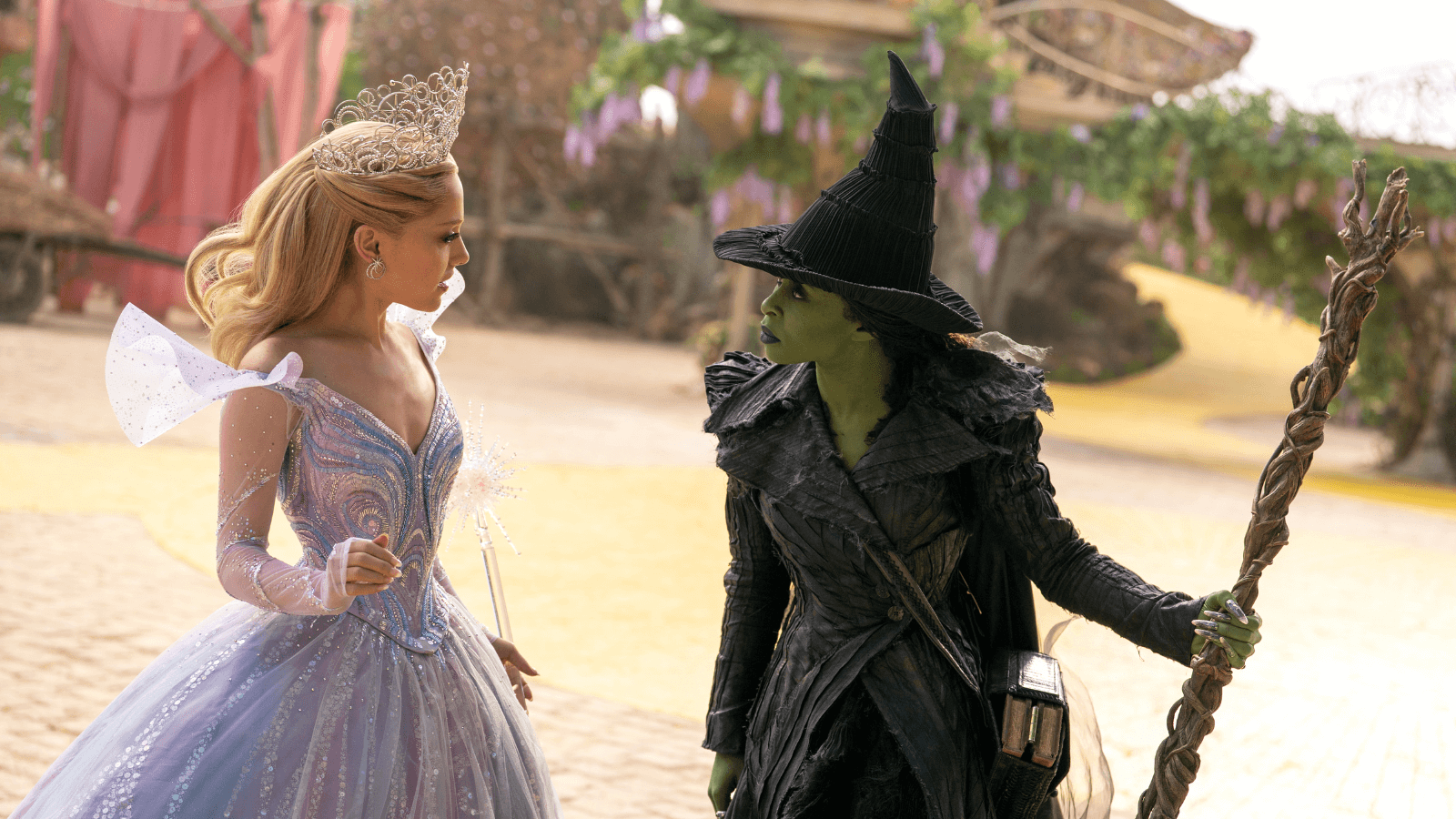

To be sure, both political and moral corruption run rampant in Oz. Elphaba’s paraplegic sister, Nessarose (Marissa Bode), has become a vindictive governor who uses her power to constrain her would-be boyfriend, Boq (Ethan Slater), when he plans to leave after realizing that she’s become power-mad. The movie involves a convoluted array of mismatched romantic couples: Nessarose loves Boq, but Boq loves Glinda, yet Glinda doesn’t love Boq. Glinda loves Fiyero (Jonathan Bailey), but Fiyero loves Elphaba, and Elphaba loves Fiyero right back. As the song says, love stinks. Meanwhile, Oz and Morrible (rhymes with horrible) target the fugitive Elphaba while putting Glinda on a pedestal—presenting her to Ozians as the bubbly “Good Witch” in contrast to her green-skinned counterpart. The tension between the former friends escalates when Elphaba inadvertently ruins Glinda’s wedding to Fiyero. The friends fight and, despite Glinda’s rather unforgivable and self-obsessed behavior in both movies, soon forgive each other.

They eventually team up for a resolution that recalls The Dark Knight (2008)—or rather, since the 1995 book and 2003 Broadway musical came first, Wicked may have influenced Christopher Nolan. Just as Batman arranged things so Gotham would lionize Harvey Dent as a hero and demonize Batman himself as a murderous vigilante, Elphaba volunteers to become the villain, staging her death so Glinda can thrive as the Good Witch they believe Oz needs—you know, “for good.” Except, even Glinda knows her behavior doesn’t qualify as “good,” yet she’s willing to accept that moniker regardless, believing that Ozians are either too stupid or emotionally incapable of handling the moral complexities of the truth. Both also decide to conceal the truth about the Wizard, a curious and dramatically unjustified reversal for Elphaba, whose unshakable morality from the first movie now wavers. But their solution merely repeats the problem created by the so-called Wizard. In Wicked, Elphaba wanted to expose his lack of magic; she spoke out and was ostracized for it. In the sequel, she compromises her morals with a scheme that replaces an ersatz Wizard with a faux witch, Glinda, who also doesn’t have any real magic, yet she intends to present herself to Oz as a genuine witch until she can learn. (Cue The Who’s “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” with the lyric “Meet the new boss, same as the old boss.”) Elphaba and Glinda have replaced one pack of lies with another.

Of course, the material sets out to explore moral ambiguities that could arise in a classical fairy tale, complicating notions of “good” and “evil” until there’s nothing left but ambivalence and equivocation. However, Wicked: For Good presents Elphaba and Glinda’s solution as a happy ending, though I found it anything but. After spending nearly five hours with these characters (too long, given the stage show’s three-hour runtime, including an intermission), it tracks that Glinda, ever vapid and hungry for attention, would want to rule over Oz—she’s superficial and has a desperate need for approval and praise. She wants attention too much to be trusted to make selfless decisions as a leader, inspiring little confidence in her reign. But it’s more uncharacteristic for Elphaba to suppress the truth or agree to a plan that deceives Ozians after spending so much energy fighting to expose the Wizard. Even more bizarre is a final shot that sees Elphaba, having effectively faked her death, walking into a random CGI desert with Fiyero-Scarecrow, apparently to become nomads. I found these choices appropriate in their postmodernism and in their deconstruction of The Wizard of Oz’s idealism, but the story is presented with an ill-fitting optimism, given the rather grim conclusion for all.

Having shot the two halves back-to-back, director Jon M. Chu maintains a similar imbalance to Wicked between the practical elements and digital ones. Once again, production designer Nathan Crowley builds elaborate, eye-popping sets; costume designer Paul Tazewell adorns the performers in luxurious costumes; and cinematographer Alice Brooks captures this iconic world in bold colors. However, much of their artistry feels neutralized by the oppressive amount of mediocre CGI, from iffy-looking talking animals to panoramic shots of banal digital landscapes. Far too many passages feel like digital filler, obligatory for a studio spectacle. Also lacking are the musical numbers, which register as serious and less inspired than, say, Fiyero’s “Dancing Through Life” stunner from the original. But the melodies and replays of “Popular” and “Defying Gravity” play throughout, now with a somber tone befitting the bleaker story.

Unlike its predecessor, I never felt swept away by Wicked: For Good, apart from the occasional acting choice by Erivo or the compelling subplot about Elphaba taking responsibility for her role in creating the flying monkeys. Perhaps it’s because the joy of discovering this world and these characters in Wicked is innately more diverting than the narrative downswing of the sequel. Maybe it’s because the digital sheen in most scenes makes the film feel unreal, like watching the cast in lavish costumes standing in greenscreen environments, acting opposite nothing. A lot of the time, it looks like little onscreen is real, and I found it challenging to connect with characters such as the Cowardly Lion, voiced by Colman Domingo, who looks about as convincing as the felines in Cats (2019). Maybe if the production hadn’t been in such a rush to meet its announced release date, the digital artists would have had more time to polish the movie’s characters and landscapes. In any case, the artificial quality of many scenes, coupled with the bafflingly cheerful conclusion, left this critic scratching his head and wondering what all the fuss is about.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review