Jay Kelly

By Brian Eggert |

Note: Netflix will release Jay Kelly into limited theaters on November 14, 2025, followed by a debut on their streaming platform on December 5.

Hollywood is having an identity crisis. Maybe it’s the looming threat of AI on artistic integrity. Perhaps it’s the billionaires and money-minded executives who continue to push the entertainment industry more toward commerce than art. It could be the dwindling box office, the rise of streaming, or the fragmentation of our culture—first by the internet, then by American politics. Whatever the reason, filmmakers have been looking inward and asking, Who am I in this business? And what’s more, Are the personal sacrifices I’ve made worth it? Recent films, from last year’s A Different Man to this year’s Sentimental Value and Is This Thing On?, have all pondered similar questions. Noah Baumbach considers them in Jay Kelly, a drama he co-wrote with Emily Mortimer about an aging star who looks back at his life and wonders whether he made the right choices. The film succeeds in no small part because George Clooney plays the eponymous lead, adding a meta layer that enriches the story with the star’s considerable charm and real-life parallels with his onscreen character.

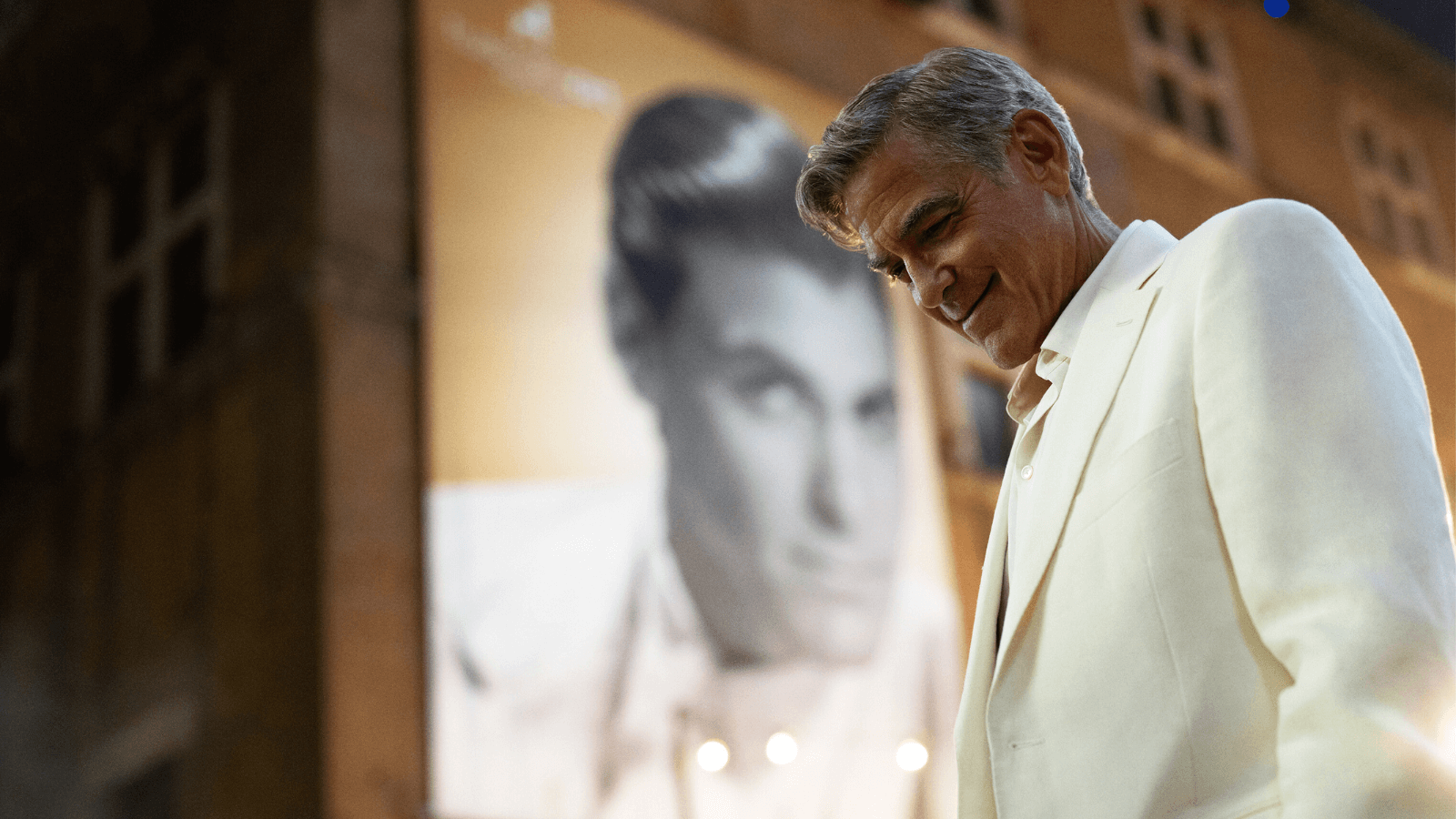

Jay Kelly opens with a quote from Sylvia Plath: “It’s a hell of a responsibility to be yourself. It’s much easier to be somebody else or nobody at all.” The film explores how superstars perform so much—for the camera, for their colleagues, and for their public—that they might lose sight of who they truly are. It’s fitting that Clooney, 64, plays Jay, given that he’s among the last of the class-act movie stars. Clooney is a modern-day Cary Grant and has entered that phase of his career where, like Grant in his North by Northwest (1959) and Charade (1963) era, his roles comment on his age. Grant is also an apt contrast to Jay for how he crafted his identity; born Archie Leech, the actor created the “Cary Grant” persona for the world’s consumption, while preserving his true self in private. Jay hasn’t made that distinction and has lost some of himself along the way. There is no one else inside but Jay Kelly. But who is he?

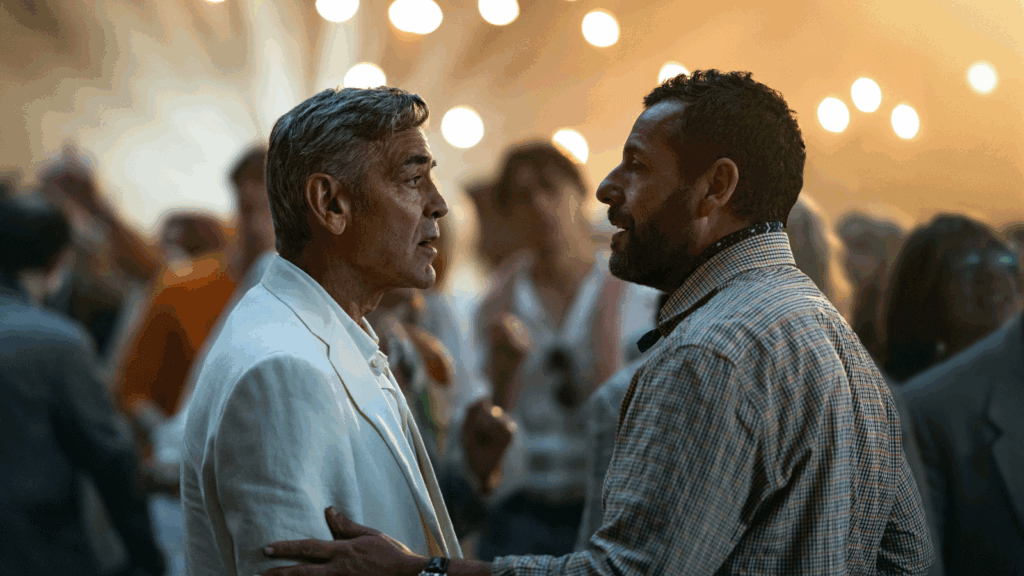

The film, produced by Netflix, the home of Baumbach’s previous three features, feels visually grounded after his last effort, the formally and intellectually ambitious White Noise (2022), with the exception of his opening shot: an impressive extended sequence, where cinematographer Linus Sandgren maneuvers around a soundstage, capturing the various players involved in the latest Jay Kelly feature. There’s Jay’s manager, Ron (Adam Sandler), on a phone call with his wife (Greta Gerwig) about their daughter’s upcoming tennis match, which he will later have to leave because of Jay. There’s Jay’s publicist, Liz (Laura Dern), who, like Ron, has worked with Jay for decades, but she’s getting fed up. And there’s Candy (Mortimer), who does Jay’s hair and makeup. Jay performs in the final scene of his latest movie and then asks, “Can I get one more?” The director and everyone around Jay assure him that he nailed it, but Jay remains ever dissatisfied. Throughout his career, he has been known for wanting to get one more take, one more chance to do it differently.

That impulse begins to seep into Jay’s real life after several events prompt him to look inward. For starters, Jay’s youngest daughter, Daisy (Grace Edwards), plans to travel around Europe with friends this summer, though Jay thought they would spend some time together between his movies before she goes to college. Then he hears about the death of Peter (Jim Broadbent), the director who discovered Jay some 30 years ago. Jay remembers his last interaction with Peter, where he turned down his struggling mentor’s request to star in his new movie, which could get funding with Jay’s name attached. Finally, after Peter’s funeral, Jay bumps into an old friend from acting school, Tim (Billy Crudup). They catch up over drinks, and all seems pleasant until Tim accuses Jay of stealing his life. Long ago, Tim auditioned for a part and brought Jay along for support. The director, Peter, resolved to hire Jay instead. Tim gave up on acting. Jay became a household name, recognized the world over.

Baumbach and Mortimer’s introspective script finds Jay reflecting on how his life “doesn’t really feel real,” and he sets out to make a change. He vows to drop out of his next project, a decision that sends his entourage reeling, especially Ron, and instead meet Daisy in Europe. He hopes to bring his mostly estranged family together in Italy, where he’s receiving an award for his career—among them, his disapproving father (Stacy Keach), who spent his life selling John Deere tractors, and his eldest daughter, Jessica (Riley Keough), who calls him an “empty vessel” and has given up on trying to have a relationship with him. As the story unfolds, Jay gradually finds himself alone. Even during a mild scandal, most of his entourage abandons him, realizing “We’re not to him what he is to us.” His family doesn’t care about his career. Only Ron remains by Jay’s side, but Jay’s selfishness tests his allegiance. Is he actually Jay’s friend or just someone who gets 15 percent of his client’s salary?

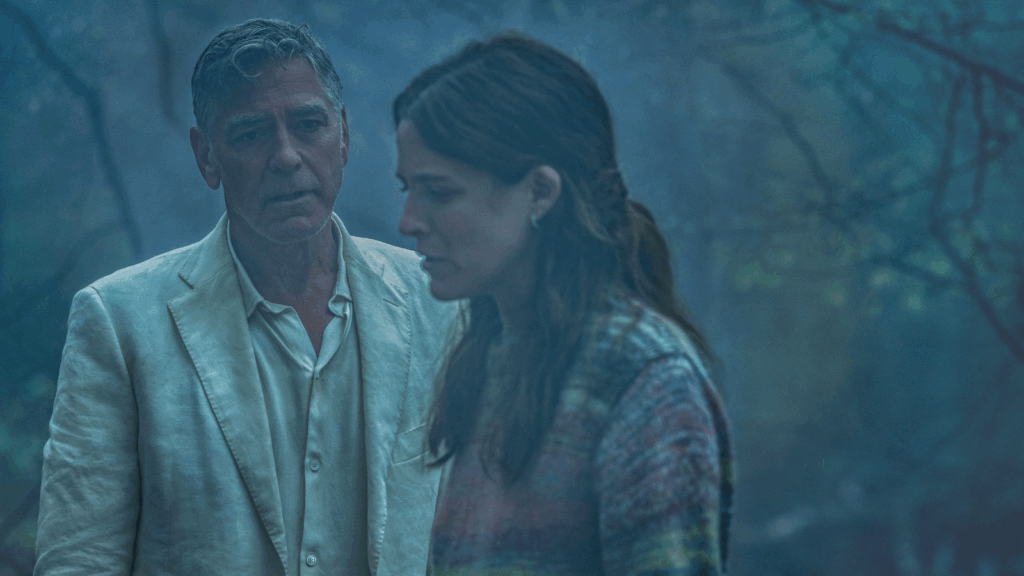

Jay Kelly’s search inward has a touch of A Christmas Carol, Wild Strawberries (1957), and, for a more recent comparison, A Big Bold Beautiful Journey (2025). While much of the film adopts a road movie format with Jay traveling by plane, train, and automobile to his career retrospective, the journey detours into dreamlike memories. He walks through doors into his past to relive how he betrayed friends and neglected his children. One sequence finds him running through a foggy forest, a pointed symbol of his personality crisis. With all of these choices, “It’s got to mean something,” Jay pleads, if only to convince himself. Clooney is excellent as the star who’s initially oblivious to his privileged life, who feels alone despite being accompanied by his staff and security personnel. The film isn’t about redeeming Jay, who never quite resolves his existential crisis. Clooney’s affable presence may make Jay sympathetic, but Baumbach never allows him closure.

It’s a clever trick, disguising Jay’s awful behavior with Clooney’s charismatic façade. But that’s the root of the problem, isn’t it? Movie stars know how to control what we see of them, and if unchecked, they will become both Dr. Frankenstein and the Creature. It’s not impossible to avoid. Take Ron’s other client, played by Patrick Wilson, who invites his wife, children, and extended family to the retrospective, where he is also receiving an award. Being an ambitious actor doesn’t mean sacrificing your home life. Jay’s sacrifices were a choice. Given this, the film’s light score by Nicholas Britell and brightly lit palette suggest a film not as intimate or probing as some of Baumbach’s best efforts, such as The Squid and the Whale (2005), Frances Ha (2012), The Meyerowitz Stories (2017), and Marriage Story (2019). However, that might be a deceptive and intentional tactic by Baumbach, given how Jay’s fans celebrate him and how the Italian retrospective shines a light on his achievements—with a montage of clips from Clooney’s career, no less. The viewer must look beyond the Hollywood gloss to see how vacant Jay has become, evidenced when Ron, in another superb performance by Sandler for Baumbach, resolves to leave Jay as well.

In a way, Jay Kelly is Cary Grant without the self-awareness. Grant was conscious of his public persona and managed it carefully. Jay knows he lies for a living, but he’s no longer able to distinguish where the lies end and he begins, if there’s even a true version of himself. In one scene, he looks in the mirror and repeats his name, trying to find a way that sounds natural. None of them do. Clooney is at his best here, playing a wounded and regretful protagonist with notes of self-reflectivity. The concept of Jay Kelly becomes an all-encompassing commentary on celebrity, on balancing one’s authentic self with the person they present to the world. Jay might find some solace in the joy his work has brought millions, but he’s stricken by a lingering sense that no matter how much regret he has, the line between movie star and human being has been lost. Baumbach has made a funny and moving Hollywood cautionary tale about the perils of losing work-life balance, about buying into the dream of becoming a star, and about how, when your career has ended, what’s left are the meaningful relationships you’ve made, if any.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review