Una Giornata Particolare (A Special Day): A Meeting of Solitudes

By Maaisha Osman | December 10, 2025

Few filmmakers have delved into the complexities of human dignity and its stark absence with as much fervor as Ettore Scola. Una Giornata Particolare (A Special Day, 1977) stands as one of his most poignant works in cinema, a quietly devastating portrait of two isolated souls navigating life under Italian fascism. The film takes place on May 6, 1938, when Benito Mussolini and the city of Rome rolled out the red carpet for Adolf Hitler and his chiefs of staff, including Joseph Goebbels and Joachim von Ribbentrop. The film portrays a delicate relationship between Antonietta (Sophia Loren), a housewife, and Gabriele (Marcello Mastroianni), a gay journalist awaiting deportation—not quite the love story that viewers would expect from the legendary pair in a lyrical screenplay, Scola directs the story of two individuals who cross paths, helpless in the face of fascism.

Born in 1931, Scola entered the film industry during the 1950s and began collaborating as a screenwriter with directors such as Mario Monicelli and Dino Risi, masters of Commedia all’italiana (Comedy Italian style). Unlike American or French comedy, Comedy Italian style confronted the grim realities of poverty, hunger, oppression, and mortality with biting irony. But A Special Day is not a comedy, even though there are some moments where some viewers may find humor. A committed intellectual and a key figure in Italian politics at the time, Scola wielded the film as a political weapon and reminded audiences of later generations of what life under fascism meant.

The opening sequence starts with six minutes of uninterrupted archival footage from a public service film of that time titled The Führer’s Trip to Italy. Shot and edited by fascist propagandists, the reel glorifies the two megalomaniacs, the imposing duce and the vainglorious führer, with mythic standing as they parade before soldiers. The lack of introductory commentary forces viewers to pay attention to the raw material. The footage ends with a chilling pronouncement from the narrator: “No citizen of Rome would miss the historic event that will seal the pact of friendship between two races destined to be allied.” The phrasing is not incidental; it underscores a central tenet of Nazi ideology—the racial structuring of society. The Third Reich’s worldview hinged on a rigid racial hierarchy, positioning the so-called “Aryan race” as “ubermenschen” (overman), while deeming Jews, Slavs, Romani, Black people, and others as “untermenschen” (underman), fit only for subjugation or extermination. Both Hitler and Mussolini saw themselves as leaders of superior races, destined to coexist in a so-called “brotherhood.”

Watching this footage in the film today, one cannot help but draw unsettling parallels to our present. The rhetoric of supremacy and exclusion on display is not confined to history; its echoes reverberate today, as almost all societies continue to grapple with hatred and the allure of dominance over the other. In a 1921 speech, Mussolini declared, “Fascism was born… out of a profound, perennial need of this our Aryan race.” He also expressed alarm about the low birth rate among the “white race” in Italy and that the progress of other races will bring the “white civilization” to ruin. According to Mussolini, only through promoting natality and eugenics could the “white race” be saved. The promotion of natality is exactly what we see in Antonietta’s character in A Special Day—the housewife who bears six children. We see in the film how the regime controls the most intimate aspects of life, as seen in her husband’s calculated plan to have a seventh child so that they will qualify for a cash prize awarded to large families, while Gabriele is penalized with a bachelor tax for not fulfilling his “duty” to reproduce.

Right after the footage ends, the camera starts with balletic camera movements in a working-class apartment complex, the largest of its kind, built in Rome during the fascist period. We see the building’s caretaker hang the Italian flag beside a massive Nazi swastika flag. Throughout the film we see the caretaker surveilling other residents who don’t participate in the rally, representing the omnipresence of a fascist government. The camera continues to examine the building’s residents, who are individually framed in their own apartments. Scola guides cinematographer Pasqualino De Santis to use gray and black tones, evoking the memory-tinged lens through which Scola remembers the days of fascism. “I was in Rome when Hitler visited,” he told the New York Times in February, 1983. “I was seven—too young for politics—and proud to wear my uniform, standing in the crowd on Via dei Fori Imperiali to watch Hitler and Mussolini pass.” But later he remembered those years shrouded in “leaden gray,” which he deliberately mirrored in the film to convey how even the colors—or lack thereof—felt during that era. The muted sepia tones, combined with the looming presence of the vast apartment complex, its units resembling prison cells, creates a claustrophobic feeling. Architecture also played a role in fascism as Swedish philosopher Sven-Olov Wallenstein said, “Architecture is no longer like a body…but acts upon the body.” The relationship between architecture and policing of Italian citizens features prominently throughout the film. Scola showed that the apartment complex is constructed in a manner that constantly obliterates privacy.

As the camera glides across the courtyard in a deliberate, unhurried zoom, closing in on the upper-floor apartment of Antonietta and her husband, Emanuele (John Vernon), the alpha male who works—albeit as a doorman—at the Ministry of Italian Africa, which managed the colonies at the heart of fascist propaganda. Within their cramped domestic sphere, power dynamics play out with quiet brutality. Emanuele wipes his hands dismissively on Antonietta’s dress, reducing her to little more than a fixture in his routine. As she rouses their six children, preparing them in crisp uniforms and polished shoes to attend the parade of the megalomaniacs, the unspoken truth settles in: she is excluded from the grand spectacle of the rally, left behind as an afterthought in a world that barely acknowledges her. Exclusion, for Antonietta, later becomes an unexpected window of a quiet revelation when she encounters Gabriele. Once her family leaves, she looks out from her kitchen window. Scola employs a striking overhead shot, emphasizing the rush of neighbors, all excited to join the rally. The framing is deliberate—everyone has departed. This absence, though subtle, is profound: why does everyone rush to see the rally of the two fascist megalomaniacs? The question lingers, one that history and philosophy continue to grapple with. Does democracy demand too much of its citizens—responsibility, thinking, self-governance—while fascism and groupism offers the deceptive comfort of obedience to ideas where you don’t have to think at all?

French philosopher Gilles Deleuze said that people don’t naturally want to think, that thought is not an instinctual act, but a strenuous, even violent rupture in our habits of perception. Deleuze challenged what he termed the “dogmatic” image of thought—the assumption that thinking is an innate, intuitive process grounded in a universally shared common sense. In contrast, he argued that genuine thought arises from confronting and disrupting these inherited assumptions. It seems to me that the tendency to avoid thinking often stems from a fear of self-confrontation, which translates into the ease of obedience. When critical reflection feels too burdensome, some people turn to authority figures who conveniently validate their existing worldview, creating the illusion of shared common sense. Nowhere is this more evident than in Antonietta’s own household, where for her husband, Emanuele, thinking would mean facing his dominant role for example.

In Deleuze’s view, fascism is not just a political system but a psychological and societal impulse, woven into the fabric of daily life, manifesting in the thirst for power and domination. Emanuele is not just a supporter of Mussolini’s regime; he is a microcosm of it. Within the domestic sphere, he embodies the same oppressive structures at play in the external world, his authority bolstered by the larger system that rewards domination. But above everything, these people who don’t want to think are also the frustrated middle class that the fascists exploit. Italian medievalist and philosopher Umberto Eco wrote in his essay In Ur-Fascism, or Eternal Fascism: Fourteen Ways of Looking at a Blackshirt, that fascism thrives on the appeal to a frustrated middle class—a class wounded by economic crisis or a sense of political humiliation. “God gives us bread and il duce defends it,” the radio narration in the film says. A portion of the Italian middle class initially embraced Mussolini’s rise to power, weary of the strikes and social turmoil that followed World War I. Mussolini’s fascist regime promised stability, order, and national pride that a lot of simple people took refuge in to feel better about themselves. These are probably the people we see in A Special Day running to see the parade of the two megalomaniacs.

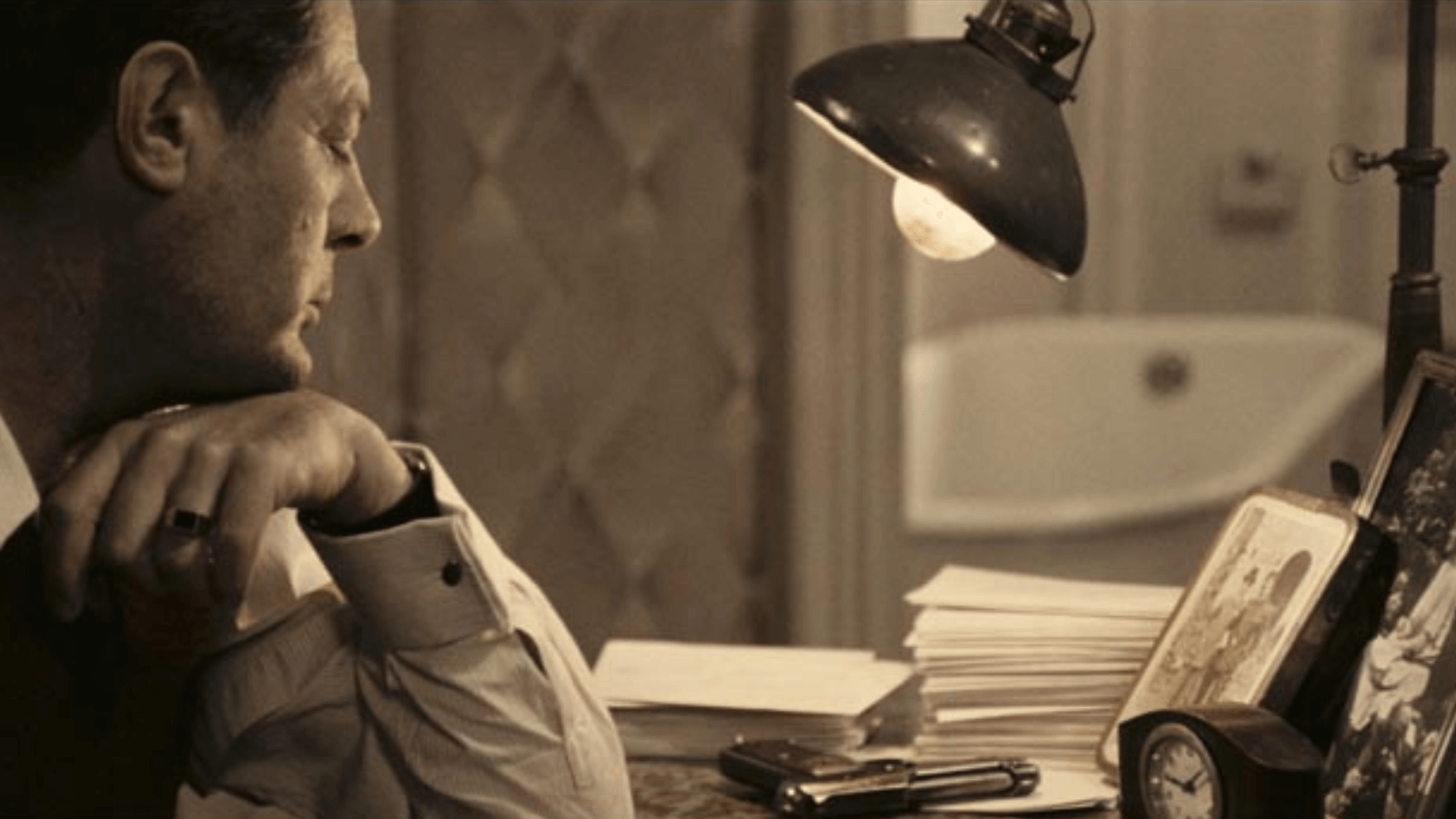

Scola captures the quiet indignities of Antonietta, her life as an oppressed homemaker, through the smallest, yet most telling, details. In a moment of solitude after her family departs, Antonietta sits in the kitchen, surrounded by the remains of their breakfast. With a resigned grace, she gathers the last dregs of coffee from their cups, blending them to form her own morning coffee. All of a sudden we see Antonietta’s mynah bird, Rosmunda. It is Rosmunda that sets the plot of the film into motion. Rosmunda flies to Gabriele’s apartment. Gabriele was fired from his job where he was a radio broadcaster and is about to be sent to confino (exile) in a remote island in Sardinia because of Mussolini’s antigay laws. We see a pile of papers and a pistol on Gabriele’s table—clearly he was having suicidal thoughts. But appropriately enough, it is Rosmunda who escaped from its cage in the kitchen, that brings the trapped Antonietta to his door. Gabriele is relieved to put aside his dark thoughts and, desperate for company, passes Una Giornata Particolare with her.

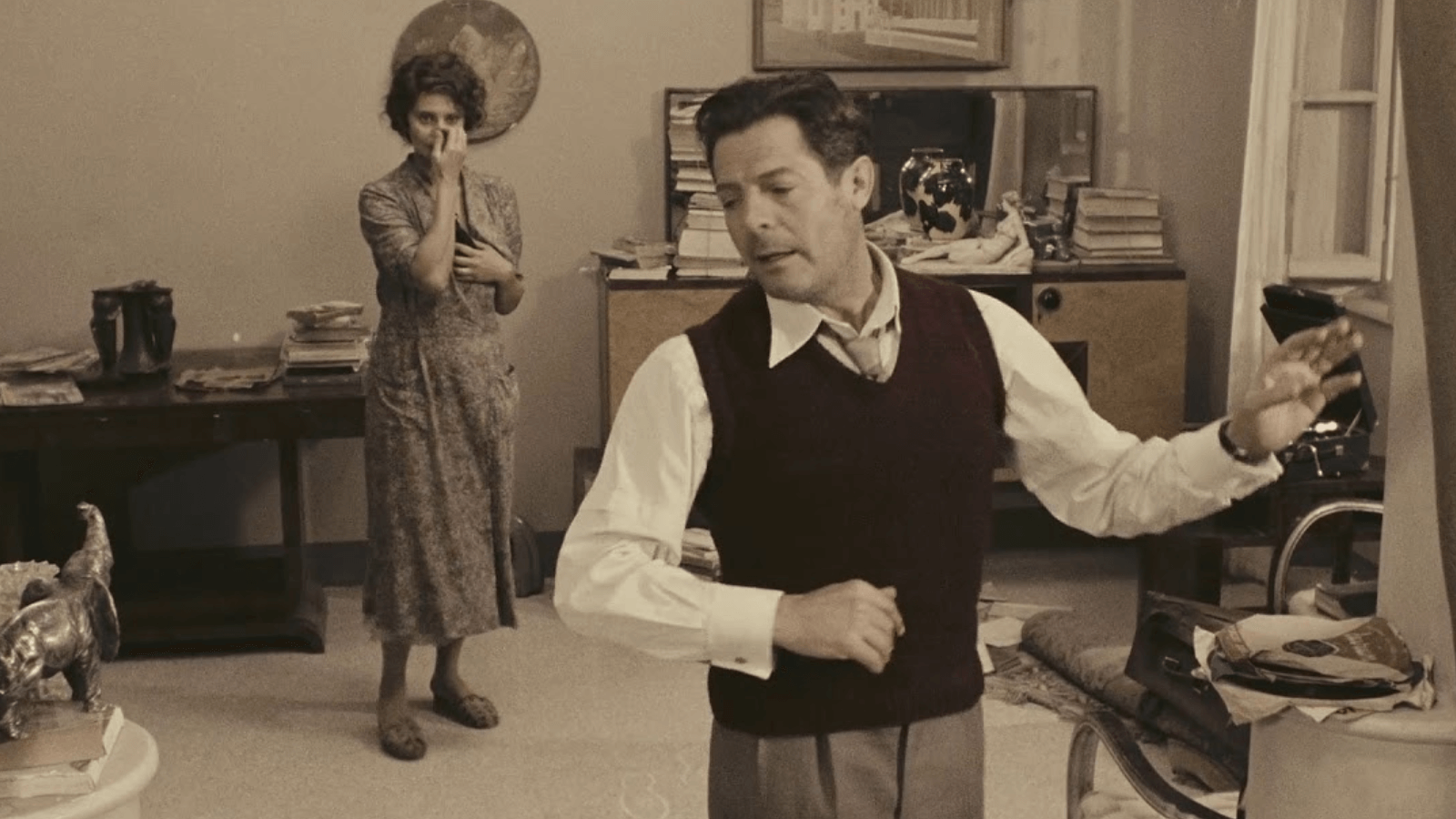

One of the most poignant moments in the film is the rumba dance—a scene that, for me, stands out as Mastroianni’s finest acting, a moment of liberation. Gabriele plays the rumba music and sings along while he does the rumba steps to teach Antonietta: “belle bimbe innamorate, gli aranci comprate hanno il magico sapore” (beautiful babes in love buy oranges, they have the magic taste). The scene is both heartbreaking but equally triumphant—a rare instance where Gabriele allows himself to embrace the joy of living, even as he faces the reality of deportation. Gabriele did not submit himself to despotism; instead, he savored life’s small moments—an act of rebellion in itself. Scola suddenly cuts the rumba music to “Giovinezza” (“Youth”), the anthem of the National Fascist Party, which Gabriele, in the mix of irony and sorrow typical of Comedy Italian style, dubs as “meno ballabile” (less “dance-able”). The noise and militaristic fanfares of the fascist rally are a counterpoint to every scene in the film, pervading the most intimate moments of daily life and creating an underlying feeling that never lets up.

In the pre-television era, the radio was a major propaganda tool for authoritarian regimes. Scola keeps the radio’s omnipresence in the film along with the opening newsreel footage to emphasize how important the media were to the fascist consensus to build and create a world of make-believe that attracted masses of people. One of them is Antonietta, who begins with a naive admiration for il duce. She even recalls fainting in the park when Mussolini rode past her—a story she retells with awe and suggests may have miraculously contributed to one of her numerous pregnancies. As Argentinian historian Federico Finchelstein explains in Fascist Mythologies, fascism functions as a form of political mythmaking, often casting leaders as mythic heroes who embody strength, charisma, and the promise of national rebirth. These figures, real or embellished, merge the personal with the political, shaping collective aspiration. Antonietta was ensnared in this political mythmaking.

Antonietta’s identity was built through entrapment and inhabitation in the fascist regime, while Gabriele’s identity was based in complete opposition. Film scholars Elena Gorfinkel and John David Rhodes write in Taking Place: Location and Moving Image, “Identity is constructed in and through place, where by our embrace of a place, our inhabitation of a particular point in space, or by our rejection of and departure from a given place and our movement toward, adoption and inhabitation of another.” But later on with her close encounter with Gabriele, she starts to question her identity when Gabriele tells her about his mother who single-handedly took care of the entire family. Antonietta lived in a building with transparent windows and open stairwells that enabled constant visibility and easy monitoring of residents’ movements. The building’s caretaker functions almost like a prison guard—though, in truth, anyone who attended the fascist rally could be seen as playing that role. Under Mussolini’s regime, Italians who opposed fascism lived in fear of the Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism, the regime’s secret police. Its vast network of informants was drawn from all corners of society, including former socialists and communists, family members, private businesses, and others enticed by the promise of employment. In such a climate, ordinary citizens had to be constantly on guard—anyone could be an informant. This type of surveillance was also explored in another anti-fascist film, The Lives of Others (2006) by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, which examines surveillance of the state, psychological manipulation, and state control in communist East Germany prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Scola demonstrates this fear of surveillance in many scenes. Every time the cantankerous caretaker meets Antonietta, she shares ugly words about Gabriele. “Hanging around certain people can get you in trouble,” she tells Antonietta. “The sixth-floor tenant is a no-good naysayer, a defeatist, an antifascist.” Antonietta and Gabriele try to evade the caretaker’s eye by slipping away to hidden corners of the apartment complex—the rooftop, boiler room, and other secluded spots. Yet Gabriele knows there is no true escape from the regime’s eyes, and throughout the day, it becomes increasingly clear that he is bracing for his imminent confino. As a gay person in fascist Italy, Gabriele faces rejection in every possible way. He notes his voice does not meet the national radio standards: “Solemn, martial and conveying Roman pride.” Scola emphasizes the regime’s characterization of Gabriele as a sterile figure, one who will neither produce the ideology of fascism nor participate in the reproduction of a new Italian, modeled on Mussolini himself. During Mussolini’s regime, when there were parades, gay people used to be arrested as “precautions.” The regime believed that gay people were corrupting society. Gabriele is forbidden from occupying certain spaces because of his views and who he is. He is dismissed from his job as a radio broadcaster, silencing his voice on the airwaves and replacing it with that of Guido Notari, an actor and regime-approved radio personality whose voice permeates the apartments for much of the film. This reflects fascism’s deep-rooted anti-intellectualism: just as many now turn to social media for knowledge, audiences then depended on state-controlled radio for information.

The situation today is not so different. Economist Daron Acemoglu emphasizes that democracy is fundamentally about self-government, which relies on informed, active, and engaged citizens. Anything that alters the flow of information will inevitably shape this experiment in self-governance. Early hopes for the internet and social media envisioned a democratizing effect—spreading information, enabling individuals to act as journalists and fact-checkers, and supporting decentralized decision-making. However, reality has trended toward centralization. Major platforms now control both information and data, deciding what people see, who they interact with, and profiting from attention. The phenomenon described by Acemoglu regarding social media centralization has likely also fueled widespread distrust in intellectuals, as people increasingly rely on social media for knowledge—regardless of whether it’s accurate, misleading, or tailored to reinforce their own beliefs.

Eco observed that distrust of intellectuals has always been a hallmark of fascism, from Hermann Göring’s infamous line, “When I hear talk of culture, I reach for my gun,” to slurs like “degenerate intellectuals,” “eggheads,” or the charge that “universities are a nest of reds.” Gabriele’s firing underscores the regime’s refusal to accept progress or modernity, and its worshippers could not tolerate a liberated gay man within a society built on toxic masculinity. Fascists consistently framed modern culture as a betrayal of traditional values and national pride. In A Special Day, this hostility is embodied by Gabriele, who is fired and deported for being a gay intellectual. Yet even in repression, he clings to life’s small joys. His irony unsettles Antonietta, the practical housewife, but it also draws her in. He jokes, he teases, he performs little acts of mischief—teaching her rumba steps, riding her son’s scooter through the apartment, wrapping her in laundry on the terrace. Still, tenderness cuts through the humor, as in his brief, heartfelt phone call to another friend (or more?), who is equally oppressed by the regime. Against Antonietta’s weary resignation, Gabriele embodies resilience through joy. In their fleeting connection, they recognize each other as kindred spirits, united in their longing for compassion and acceptance. “You’re not like the others, you’re here with me,” he tells her.

Apart from the caretaker in the apartment complex, they appear utterly alone in the building—suspended in a timeless moment, surrounded by a strangely vacant space. The caretaker sneers at Gabriele as an anti-fascist and warns Antonietta to stay away. Gabriele himself rejects the fascist code of masculinity: “I’m not a husband, a father, or a soldier,” he insists. Antonietta, bewildered, mistakes his refinement for flirtation and completely misses the point. Then, as the triumphal radio broadcast exalting “the magnificence of fascist Italy” and its new so-called brotherhood with Germany swells to its peak, Gabriele bursts out after Antonietta kisses him. “I am a faggot. A faggot. That’s what they call us,” he says. But Antonietta apologizes soon after.

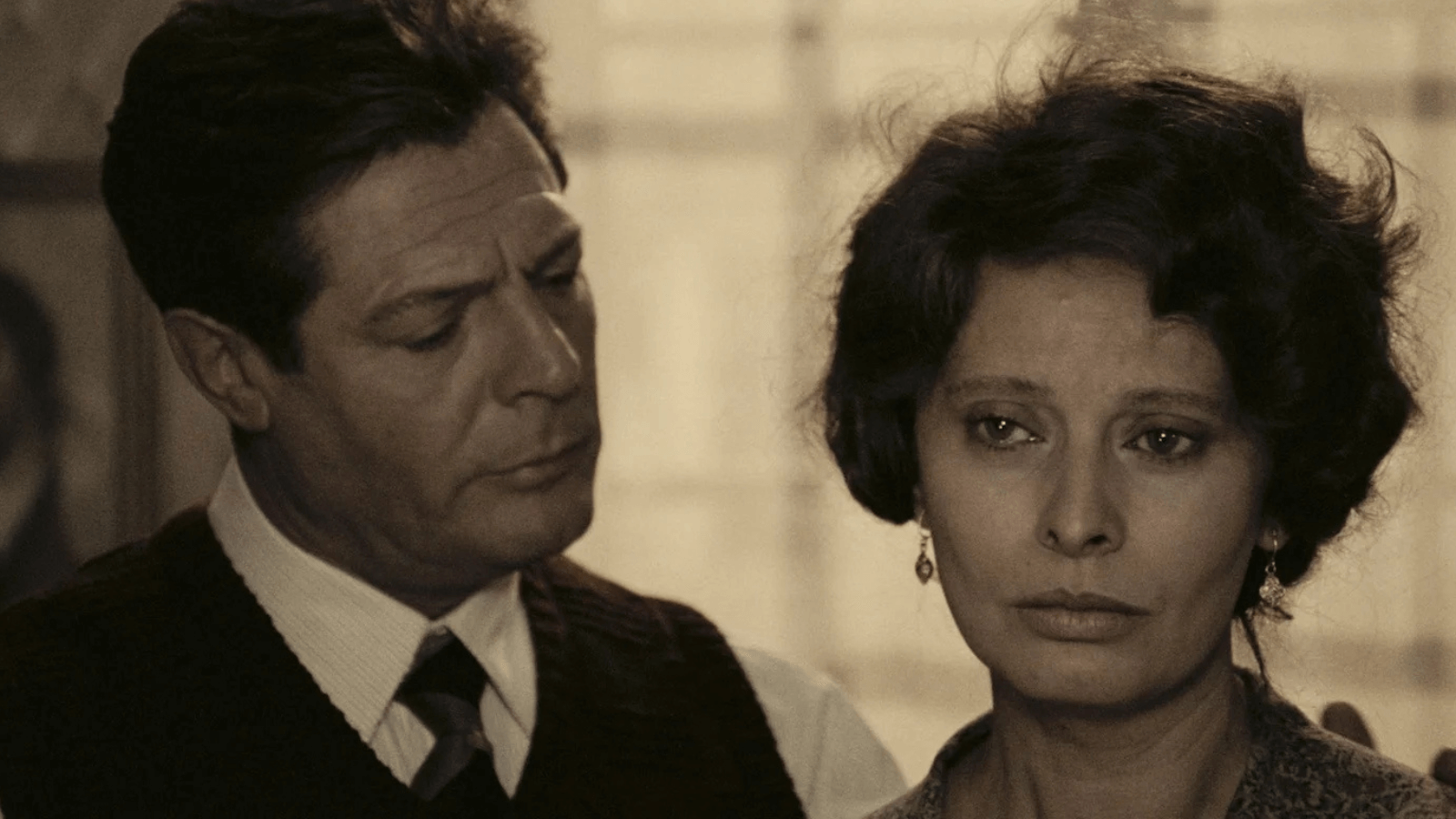

The relationship of the two characters deepens in a tender and a humane scene when Antonietta makes love with Gabriele. The act is less about passion and more about tenderness. It’s a moment where two marginalized people share a fleeting reprieve. The real intimacy between them lies in their emotional nakedness, in being seen and understood, however briefly. Scola portrays the scene with remarkable restraint, avoiding any trace of sensationalism. The camera lingers on faces rather than bodies, attuned more to feeling than action. The film reaches its emotional peak in this whisper-soft seduction, the camera moving between Gabriele and Antonietta’s faces, capturing the ache, confusion, and courage that pass across them. Both will likely carry the memory of this day silently for the rest of their lives. Yet it has marked them irrevocably. Even as daily life resumes, something inside each of them has shifted. By ending on this quiet but powerful note of inner resistance, Scola offers a subtle vision of defiance—one not grounded in ideology, but in the radical act of human connection. It’s a path anyone might take, through compassion, solidarity, and the courage to connect across imposed boundaries.

As Scola himself explained, “Cinema has to reflect the different moods of life. Life has its tragedies, sadness and pain. But it also has its moments of joy and hope.”

Scola’s role in shaping Comedy Italian style remained central to his reputation. Although A Special Day is not a comedy, Scola still felt compelled to make us laugh in various scenes such as when the caretaker asks a resident returning from the parade what Hitler is like, and the resident replies, “Ah, è bellissimo! (Ah, very beautiful).” Equally important is Scola’s use of diegetic sound, especially the ever-present radio broadcast that threads through the film. The radio, blaring accounts of the fascist rally outside the apartment building, functions as a constant reminder of the world beyond the characters’ private encounter. Its ceaseless intrusion highlights the tension between the intimate, fragile moments Antonietta and Gabriele share and the overwhelming public spectacle of fascism that dominates their reality. More than just background noise, the radio symbolizes state propaganda, underscoring how deeply Mussolini’s ideology penetrated everyday life and pressed individuals to conform. This continuous “Big Brother” soundtrack creates an unease that lingers even in the film’s most tender passages, mirroring the historical anxiety of a society steadily surrendering to the brutality of totalitarianism.

Even amid the uneasiness, Antonietta experiences making love with pleasure for the first time. As Simone de Beauvoir argued, women’s sexual experiences are deeply shaped by societal structures and gender roles that condition them toward passivity and objectification, often leaving them alienated from their own desires. For much of her life, Antonietta’s sexuality was defined by her husband’s desires and reproductive demands rather than by any recognition of her own pleasure, but in this moment, she begins to reclaim a sense of agency over her body and desire. At first, Scola hesitated to cast Loren, worrying she might be too glamorous for the role. She initially struggled with the director’s demands, giving up her own makeup team and wearing a single house dress for the entire film. But within a week, she adapted fully to his vision. Scola later remarked that Loren was “an intelligent woman first, and an actress second.” Loren was initially hesitant to take on the role, but deep down inside, she believed she was “born with this character.” She ended up giving the best performance of her life in A Special Day, along with Two Women (1960) by Vittorio De Sica.

Mastroianni also delivers what may be the finest performance in his career in A Special Day. Throughout the film, Mastroianni reveals Gabriele’s sexuality in a few telling gestures. It is also worth emphasizing that Mastroianni was far more than the “Latin lover” stereotype often imposed by Western critics—a label he disliked, and understandably so. His body of work reveals an extraordinary range, from portraying a Marxist intellectual in Mario Monicelli’s The Organizer (1963) to playing Federico Fellini’s alter ego in 8 1⁄2 (1963). Mastroianni stands as one of Italian cinema’s most versatile actors who could easily put his raw emotions into different roles, despite allegedly never learning his lines. Scola said about Mastroianni with whom he shared deep friendship and collaborated on many films, “I loved his ability to become a character so completely…that’s why a great figure like Fellini chose him, almost as an alter ego at least in two great films because Marcello could become any character.”

At the time of Mussolini and even when Scola made the film in 1977, gay men were not welcomed in any aspects of Italian life. Many like Gabriele were sent to a confino, best described as a form of quarantine implemented to guarantee the health and safety of regime supporters. It is worth considering French philosopher Michel Foucault’s discussion of quarantine in Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, where he traces the shift in criminal codes from the bodily torture of earlier eras to the seemingly “gentler” punishment of prison sentences. Foucault argues this change did not arise from society’s growing enlightenment, but from deeper transformations in power and control. Foucault describes how “the spread of disease” serves as a crucial metaphor for the development of disciplinary power. Foucault uses the example of the plague to illustrate how societies, in attempting to control disease, developed techniques of surveillance, partitioning, and individualization that would later be applied to other areas, including prisons. In A Special Day, Gabriele is seen as the one “spreading the disease” and is thus quarantined, as he will neither contribute to the ideology of fascism nor participate in the biological reproduction of the Italian modeled on Mussolini himself. A Special Day shows the power of fascist surveillance and control, but it most importantly shows that it is possible to resist totalitarian ideas even in the quietest possible ways. In fact, people like Gabriele who resisted went on to lay the groundwork for a postwar Italy and Europe that had been ravaged by the ideology of fascism.

Every single line of dialogue in A Special Day is worth highlighting. Scola began his career as a journalist and cartoonist before moving into screenwriting. As a teenager, he contributed to the satirical magazine Marc’Aurelio, and he made his directorial debut in 1964 with Let’s Talk About Women after collaborating on screenplays of over eighty films. A Special Day is both written and directed by Scola. Every time I watch the film, I feel compelled to highlight one line of dialogue or another—until I realize I want to reconsider almost every single line, because each one carries significance. One particularly important point in the script only became clear to me with the help of my partner, who introduced me to this film—a gift for which I will always be grateful. Scola shows the obsession with pronouns in the fascist regime. Throughout the film, Antonietta uses the pronoun voi, while Gabriele uses lei, both of which translate to “you” in English when addressing someone formally. At one point, Antonietta tells Gabriele, “Stop using lei, you know it’s forbidden.” This is a reference to Mussolini’s language policy: he banned the singular formal pronoun lei because it also means “she,” deeming it too feminine and insufficiently aligned with fascist ideals. It is only later in the film, after Gabriele reveals to Antonietta that he is gay, that she recognizes the absurdity of using voi. From that moment on, the two begin addressing each other with tu, the informal form of “you.” In these small details, we glimpse the true genius of Scola’s screenwriting.

Scola’s legacy as a filmmaker is vast. Over his career, he directed 27 feature films, produced numerous documentaries, and collaborated on the screenplays. Beyond his artistic contributions, he was also a committed activist, serving nearly 50 years as a member of the National Association of Cinema Authors. Deeply aware of the fragile state of Italy’s education system and the threats to free thought in the media, Scola championed Italian cinema as an essential tool for cultural formation. He believed that filmmaking, film viewing, and the study of film history nurtured critical awareness in young people and ultimately served the public good. To that end, he fought to safeguard production jobs at Cinecittà—Italy’s largest film studio—and to preserve Rome’s tuition-free national film school. In the 2010s, as the Italian government under former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi slashed arts funding, Scola became increasingly engaged in movements to defend cultural spaces. From the outset, he stood alongside giants like Rossellini, De Sica, Visconti, and Fellini, yet distinguished himself through a more measured and collaborative approach.

Rather than seeking the spotlight, Scola thrived in collective creative environments. His collaborations with actors—particularly Vittorio Gassman and Mastroianni—proved decisive, as many of his stories were crafted with their voices and sensibilities in mind. Mastroianni, for instance, played a crucial role in shaping the character of Gabriele in A Special Day. Italian film critic Gian Piero Brunetta observed that “for Scola, laying claim to authorship always emerged from the activity of a workshop, with the enhancement of many types of knowledge, the result of skills that successfully come together to create a product capable of making the most dialogue and interaction.” This ethos of shared authorship and creative exchange is deeply embedded in A Special Day, where the interplay between script, direction, and performance achieves a rare balance of intimacy and universality.

Many aspects of A Special Day show how an authoritarian regime works—from controlling minds through propaganda; administering intimate aspects of personal life, surveilling, deporting people who don’t believe in state propaganda; and exterminating people they consider inferior. Now, more than 80 years after the fall of twentieth-century fascism, we find ourselves on the precipice once more. A Special Day is a genius film that feels frighteningly contemporary—not merely a historical reflection, but an urgent warning. Eco reminded us, “Freedom and liberation are an unending task.” Scola underscores this by showing that even one day, one encounter, one special moment can spark the eternal beginning of liberation.

“In the dark times

Will there also be singing?

Yes, there will also be singing.

About the dark times.”

– Bertolt Brecht

Bibliography:

Acemoglu, Daron, and Simon Johnson. “The Urgent Need to Tax Digital Advertising.” Network Law Review, Spring 5, 2024.

De Beauvoir, Simone. “The second sex.” In Social theory re-wired. Routledge, 2023, pp. 346-354.

Eco, Umberto. “Ur-fascism.” The New York Review of Books, 22, 1995, pp. 12-15.

Finchelstein, Federico. Fascist Mythologies: The History and Politics of Unreason in Borges, Freud, and Schmitt. Columbia University Press, 2022.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Pantheon Books, 1977.

Lanzoni, Rémi, and Edward Bowen, editors. The Cinema of Ettore Scola. Wayne State University Press, 2020.

Snir, Itay. “Gilles Deleuze: Thinking as Making Sense Against Common Sense.” Education and Thinking in Continental Philosophy: Thinking against the Current in Adorno, Arendt, Deleuze, Derrida and Rancière.Springer International Publishing, 2020, pp. 83-113.

Kamm, Henry. The New York Times, “Ettore Scola’s Historic Backdrop,” February 20, 1983, https://www.nytimes.com/1983/02/20/movies/ettore-scola-s-historic-backdrop.html. Accessed August, 2025.

Yakir, Dan. “Ettore Scola.” Film Comment, 19, no. 2, 1983. pp. 41-43

Yannis, Chatzantonis. “Thinking and Learning in the Philosophy of Gilles Deleuze.” Journal of Philosophy of Education, Volume 55, Issue 4-5, August 2021, pp. 852–863.

Maaisha Osman is a health care policy journalist based in Washington D.C. She has written for Inside Health Policy, STAT, and Point of View Magazine. A lifelong cinéphile, she dreams of writing book of essays on films by her favorite directors like Ingmar Bergman, Andrei Tarkovsky, Satyajit Ray, Rwitik Ghatak, François Truffaut, Wong Kar-wai, and others.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review