The Rum Diary

By Brian Eggert |

Though it took much conviction on the part of producer Johnny Depp to bring to the screen, The Rum Diary is a film without much conviction in its storytelling. Bruce Robinson, in the director’s chair for the first time in almost two decades, and working from his own script for the first time since longer than that, delivers a picture that took a considerable time to hit theaters. Based on the novel by Gonzo journalist and lovable radical Hunter S. Thompson, the film brings Thompson’s origins as a writer to the screen. Although, after this film, one wonders if frequent Thompson documentarian Wayne Ewing (Breakfast with Hunter and Animals, Whores, and Dialogue) couldn’t have told a more compelling, less conventional version of the story. Distributors at Film District should see a moderate return on their investment, given its star and seemingly party-crazed subject matter, but Thompson devotees will no doubt feel disappointed for its lack of substance.

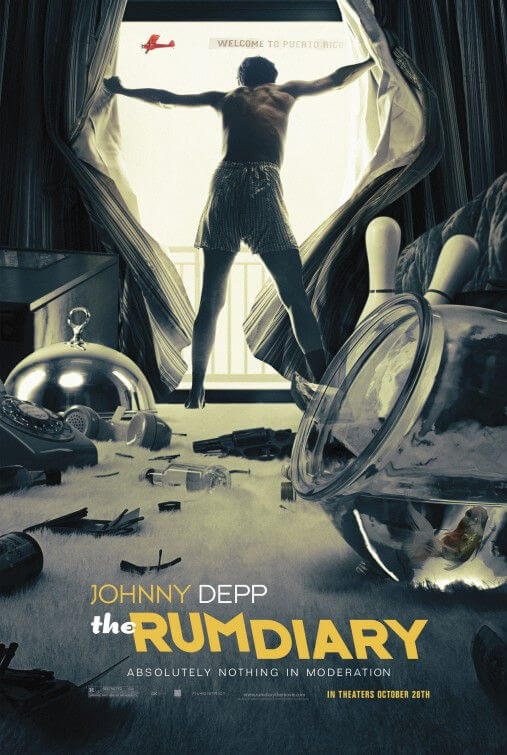

The film opens with a scene straight from The Hangover, as journalist Paul Kemp (Depp) wakes up in 1960 San Juan, Puerto Rico, with a devastating headache and liquor bottles littered about his hotel room. He arrives late at the San Juan Star for an interview with his new editor, Lotterman (Richard Jenkins), whose paper serves American tourists a heavy diet of horoscopes and light news. Kemp (Thompson’s view of himself) makes friends with Star photographer Sala (Michael Rispoli, playing the resident Dr. Gonzo). They drink rum, lots of it, watch cockfights, and explore various drugs, taking in Puerto Rico’s nightlife without a care. Then, during the day, Kemp sees American interests making life impossible for locals, all subject to men with suits and money brokering deals on local land. Meanwhile, Kemp is pursued and seduced by slimy businessman Sanderson (Aaron Eckhart), whose girlfriend Chenault (Amber Heard) catches Kemp’s eye. Sanderson wants Kemp’s journalistic pull to spin an illegal land deal to the public, and he’s willing to pay; Chenault just wants Kemp. But the self-destructive atmosphere driving Puerto Rico doesn’t destroy Kemp or corrupt him—it helps him hit upon an angry, take-no-prisoners writing style that defined Thompson.

The film’s behind-the-scenes developments prove more interesting than the actual film, however. Thompson’s novel, written in 1961 but unpublished, was purportedly rediscovered by Depp during the actor’s stay in the basement of Thompson’s Colorado compound while researching his role in Terry Gilliam’s adaptation of Thompson’s book Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. The actor found the manuscript, convinced Thompson to publish it in 1998, and together they sought a film adaptation with indie studio production head Holly Sorensen. After the film failed to progress according to plan, Thompson, as he often did, sent an angry note, telling Sorensen, “It’s like the whole project got turned over to zombies who live in cardboard boxes under the Hollywood Freeway. I seem to be the only person who’s doing anything about getting this movie made.” Sorensen’s studio later shut its doors in 2001, development halted, and in 2005 Thompson committed suicide.

Not until Depp sent the book to Robinson did progress resume. Robinson had retired from filmmaking, his last directing credit being Jennifer 8 in 1992. Before that, he had put two hilarious, dark British comedies to film: Withnail and I (1987) and How to Get Ahead in Advertising (1989), the former a tale of two boozehounds in northern England (both films starred Richard E. Grant). When he agreed to adapt Thompson’s book, Robinson had been sober for six years but couldn’t find a clear-headed way into the script. He opted to drink himself into the mood of the story, partook in alcohol once more to finish the script and filming, and got back on the wagon again after production wrapped. The onscreen, off-screen parallel of writers finding their voice in print, be it through rage or booze, makes the finished film much more compelling than it actually is.

Alone, what’s onscreen feels wanting, hampered in part by a single, unnecessary glint of surreal Gonzo imagery—Sala’s tongue extending several feet out of his mouth (courtesy of bad CGI) in a psychedelic-induced hallucination—and a failure to establish its themes earlier in the story. Moreover, Kemp and Chenault’s romance goes underdeveloped, and the community of Star reporters is never fully sketched out. Only in the last third do we grasp that The Rum Diary is not about Sanderson’s shady land deal or Kemp’s substance abuse, but about a writer finding his voice for the Common Man against “The Bastards” in power. The film is advertised with plenty of shots from early in the story when Kemp’s booze intake is greater and things aren’t so political, and the tone follows that cue, never sure if it wants to be something substantial or something more akin to a fire-breathing joyride through Puerto Rico.

Depp’s inconsistent narration doesn’t help, popping in occasionally but never clearly identified as either Kemp’s inner thoughts or a reading from Kemp’s pages. At times, Depp’s performance feels like a younger version of his Thompson from Gilliam’s film—his voice and mannerisms a spot-on interpretation. At other times, Depp injects too much of Captain Jack Sparrow’s buffoonery (we’re always expecting Depp to ask, “Why is all the rum gone?”) into what sometimes passes for a charismatic, even suave character. Surprisingly, Depp’s wavering portrayal becomes the film’s biggest downfall, next to the screenplay. Rich performances by Jenkins, Eckhart, and especially Giovanni Ribisi’s alcohol-soaked, pseudo-Nazi, ex-journalist Moburg steal the show away from its star.

Overall, Robinson’s take feels conventional, in spite of going against type and leaving the good-vs-evil Sanderson conflict open-ended. The film’s true conflict concerns Kemp discovering his writer’s voice, but so much time is spent damning Sanderson that audiences are bound to feel robbed for not having witnessed his comeuppance onscreen. Perhaps the problem is cohesiveness; the film either needs more or less of it—more consistent themes or a more irregular story structure would have livened up the material and given it cinematic purpose. For such nonconforming qualities, some call Gilliam’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas a frenzied and disorganized film, but it captured Thompson’s spirit, his rocking at the typewriter as he punches keys to some acerbic tirade about the state of America. Robinson’s film proceeds on conventional terms and doesn’t pay off in conventional ways, and it doesn’t challenge us in the way Thompson’s writing does either. That Robinson failed to relate either a conventional or unconventional take, only a muddled one, on Thompson’s book makes the long wait for The Rum Diary’s arrival on film feel in vain.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review