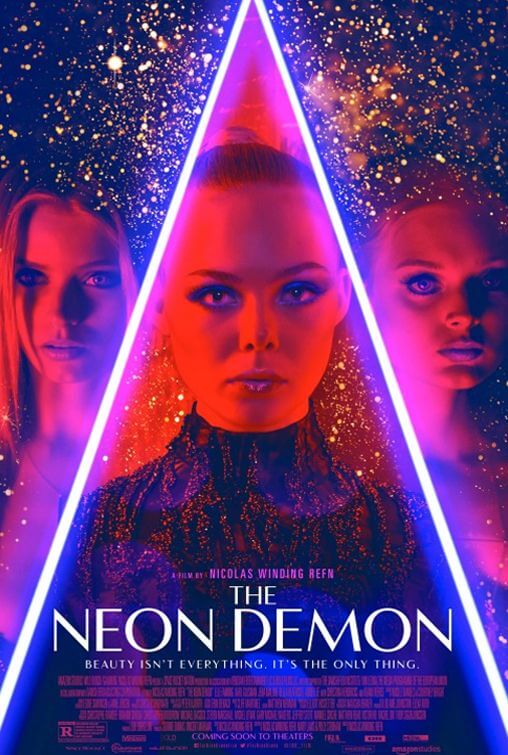

The Neon Demon

By Brian Eggert |

Nicolas Winding Refn explores icy and merciless fashion models in The Neon Demon, another of the writer-director’s visual stunners, despite being measuredly paced and narratively simplistic. With far less humanity than Drive, his latest, which debuted at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival to a mixture of boos and cheers, has much in common with his efforts Valhalla Rising and Only God Forgives. Most of Refn’s films possess a thematic obviousness that, when combined with his meticulous, sometimes-indecipherable visuals, seem to have more subtext than they really do. The first shot of The Neon Demon links women, beauty, and violence in a striking way that becomes more shocking and bold as the film proceeds, but the themes never grow more complex than this basic idea. It’s all presented in such a way that, by the final frames, viewers will either be asking themselves “Is that all there is?” or worse “What was that all about?”

This critic was in the former camp. The Neon Demon shows Refn remains in adulation of Stanley Kubrick and David Lynch, as his so-called horror film is unmistakably influenced by The Shining and Mulholland Dr. The story involves the appalling and dreamlike descent of a would-be “It Girl” in Los Angeles like the latter film, and contains a haunting air of something other-worldly like the former (there’s even a door, of sorts, that opens to a heavy flow of blood). Elle Fanning plays Jesse, who arrives on the L.A. fashion model scene only just after she arrives in town, seemingly a bumpkin whose natural beauty gets her far, and fast. The head of her modeling agency (Christina Hendricks) calls her “perfect” despite Jesse being just sixteen. “Eighteen is too on-the-nose,” she’s told. “Whenever anyone asks, say nineteen.” The next day, she’s having gold paint hand-applied to her naked body by the industry’s leading creeper-photographer (Desmond Harrington).

Meanwhile, Jesse befriends Ruby (Jena Malone, excellent), a makeup artist on both models and cadavers (get it?). Ruby invites her to a party alongside fellow models Gigi (Bella Heathcote) and Sarah (Abbey Lee), girls who are supposed to have Jesse’s back. Instead, they envy her effortless natural beauty, which they’ve tried to replicate through countless operations and augmentations—leaving them to appear, even behave downright vampiric. Indeed, everyone wants a piece of Jesse, some quite literally. For the time being, she lives in a squalid Pasadena motel, populated almost exclusively by young women looking to make it big. Keanu Reeves plays the seedy motel manager. He reminds us how frightening he can be (see Sam Raimi’s The Gift) in a scene where he tries to break into her room to do the unthinkable. Malone, too, wonderfully demonstrates her character’s more disturbed side in a scene when she projects her feelings onto a corpse.

Refn doesn’t investigate his characters in any meaningful way, arguably by design. Save for some late-film behavior by Ruby and Sarah, these people are all surfaces. Very pretty on the outside, but otherwise soulless and empty. Early on, we realize Jesse feigns some of her innocence. She may be virginal, but she knows how her beauty affects people; she knows how she has something pure that others envy; she knows they desire her, and how it turns them into jealous monsters. What’s more, she takes pleasure from the agony she causes, but she puts on an air of blamelessness—even as the corner of Fanning’s mouth shows the faintest hint of a smile when she, rather than Sarah, catches the eye of a top designer (Alessandro Nivola). Of course, Sarah, Gigi, and Ruby have their own major hang-ups, leading to an unforgettable last twenty minutes.

Carrying on at a deliberate pace, the film boasts a rather amazing synth score by Cliff Martinez (Contagion), full of brooding hums and 80s-style tempos. Other than the 80s being a decade of excess, which instantly aligns with this film’s themes, there doesn’t seem to be much reasoning behind the choice of the score’s style. Long, tonally heavy shots in dark lighting are contrasted by bright neon colors—such as a runway sequence where Jesse sees a series of triangles glowing in green and red. Like the models in the film, they’re gorgeous aesthetic compositions, but their meaning is elusive, if not entirely nonexistent. So when the film’s detractors call it“hollow”, perhaps they’re getting the point a little too well. From that perspective, The Neon Demon is structurally and thematically sound. The configuration of every shot, the delivery of every line of dialogue, and the lighting and blocking of every scene has been carefully modulated to Refn’s overelaborate specifications, but the ornate look and feel of The Neon Demon doesn’t contain enough substance to justify the ostentatious design.

Gorgeous to behold and boasting a score worth downloading, The Neon Demon may contain an astounding third act, but Refn takes far too long to establish what is blatantly obvious within the first few scenes. His attempts at hypnotic splendor, which recall the dreamscape in 2001: A Space Odyssey—except with neon, strobe lights, and human bodies—do not transport the viewer or transcend the material. The film’s hallucinatory sequences feel empty, and as though Refn was trying but failed to achieve a certain significance or, as suggested, evoke the emptiness of his subject matter. Either way, we’re left feeling appreciative of his formal confidence, yet emotionally detached. Although Refn’s horror-styled critique of how women are used, objectified, and forced to see each other on those terms remains apt and relevant, the heavy-handed, sometimes indiscernible visual metaphors don’t have anything more to say on the subject except that this trend is bad. If that’s all Refn was going for, mission accomplished.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review