Stars at Noon

By Brian Eggert |

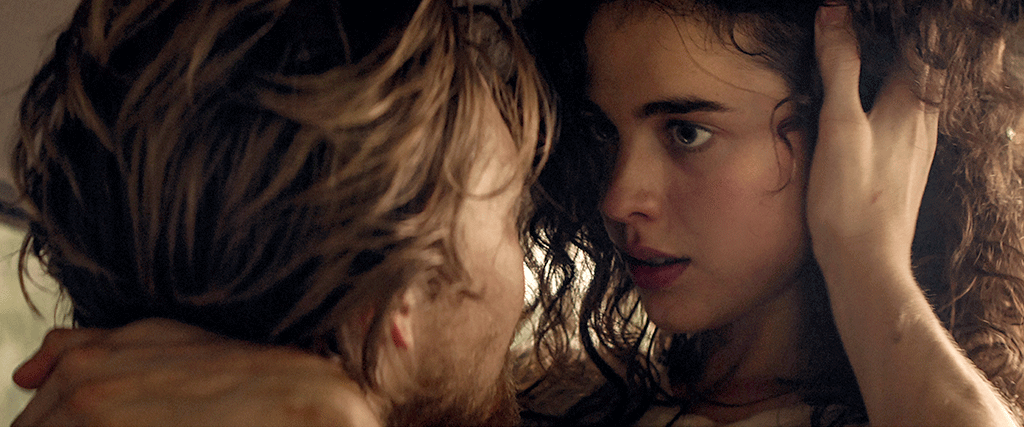

Stars at Noon is Claire Denis’ latest interrogation of how colonizers behave in a foreign land. Equivocal as ever for Denis, the film takes place in an unnamed, poverty-ridden Central American country, probably Nicaragua, and finds an American woman and a British man connecting out of desire, necessity, and also familiarity. Often, when people travel to another country, they’re pleased to find others like them and would rather engage with their compatriots than the locals. Something similar happens with Trish Johnson (Margaret Qualley), who claims to be an American journalist yet has found herself wandering the country, desperate and unable to afford a plane ticket. Still, she treats the land and its people as though they’re beneath her—she cries out at one point that it’s a “hopeless country.” When she meets Daniel DeHaven (Joe Alwyn), an attractive British agent for an oil company dressed in an all-white suit, she acknowledges him as a human being, perhaps because of his skin color. Based on Denis Johnson’s 1986 novel The Stars at Noon and resituated to the present instead of the Nicaraguan revolution of the 1980s, the film explores the region’s murky politics and exploitation by capitalist powers through the guise of an espionage thriller. But more than spycraft or intrigue, Denis finds herself invested in the sensual relationship between Trish and Daniel, two people who connect as strangers in a strange land.

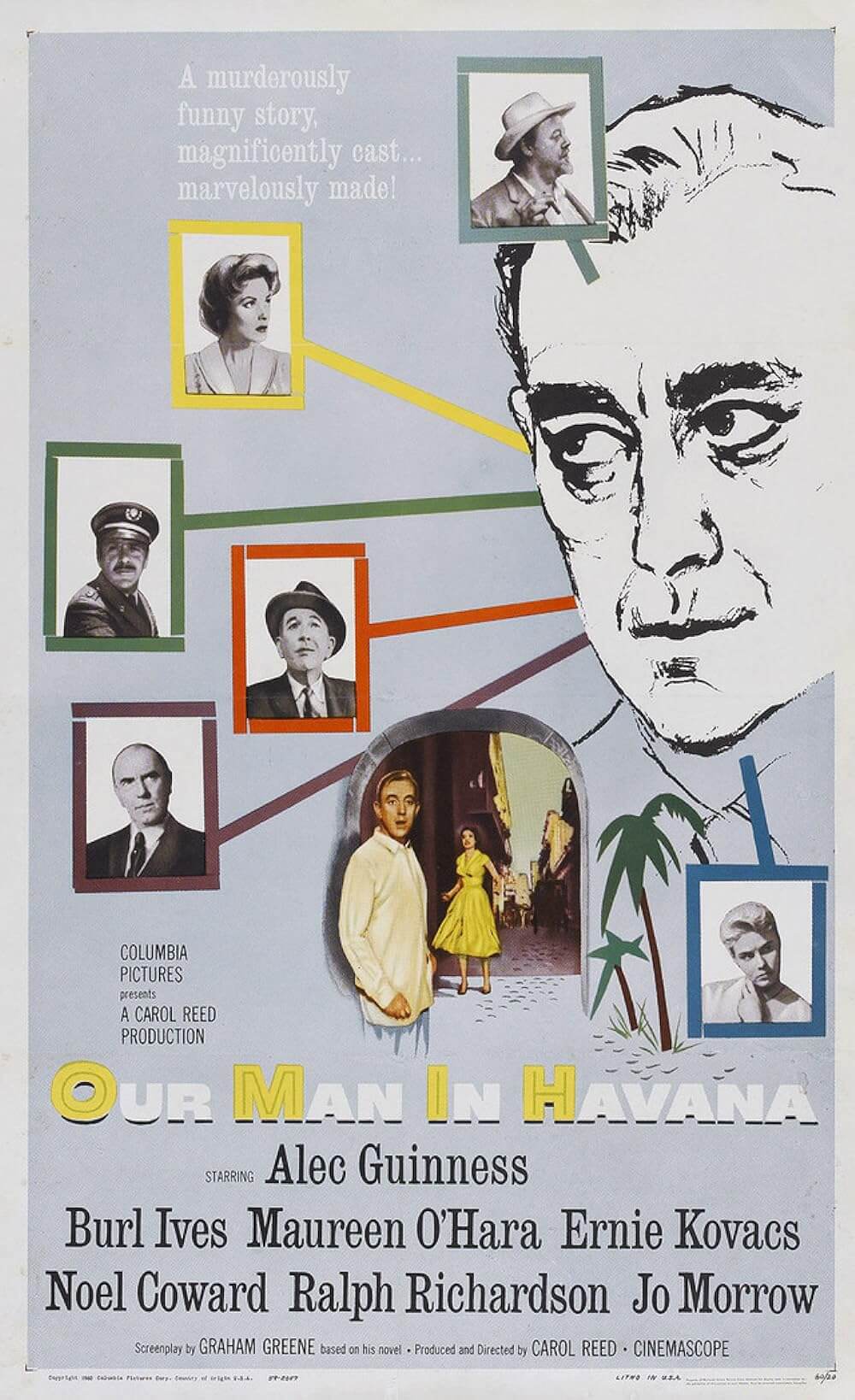

In another filmmaker’s hands, Stars at Noon might have turned into a boilerplate Hollywood product set in an underdeveloped country that’s discriminately focused on white people. That’s partly true of this film, except it’s for a good reason. With Denis at the helm, the film aligns with her films Chocolat (1988), Beau Travail (1999), and White Material (2009), which investigate the relationship between colonizers and the colonized in terms of sex, culture, and power. Denis thinly applies the spy and seduction tropes seen in similarly themed material—such as Carol Reed’s Our Man in Havana (1959) and other Graham Greene fiction—but she folds in details that emphasize her critique. For example, note how Trish handles currency. When she pays with local córdobas, she hands over unspecified piles of the stuff cupped in her hand without counting it; when she pays with precious American dollars, they are neatly filed and folded. Denis finds many subtle and sometimes more unmistakable ways to underscore Trish and Daniel’s sense of superiority and disconnection from the reality of the country. Her critique is a constant undercurrent below the vague political machinations and erotic coupling.

When the film opens, it introduces Trish floundering through a world with an oppressive state military on the streets, masks that reveal the contemporary setting during COVID-19 times, and rampant poverty. She struggles to buy a Coke (“Only Sprite today,” a clerk tells her), meat, and shampoo, and she needs a plane ticket back to the states. With no other options, Trish alternates between the beds of a local politician and a sublieutenant, which earns her some protection and the occasional payday. Why she’s in-country at all remains unclear. Trish claims to be a member of the press but has no press card—and later, in a video call to an editor (John C. Reilly) where she asks for a paying assignment, he flat out tells her, “Just admit to yourself you’re not a journalist.” And so, when she meets Daniel at a bar in a hotel reserved for wealthy foreigners, Trish tells him that she came because she “wanted to know the exact dimensions of Hell.” Then she offers to sleep with him for fifty dollars, insisting it’s more for the air conditioning than the money. Even so, she admires his pale skin (he’s like getting “fucked by a cloud”) and allows herself to fall asleep in his presence—something she never does, she says. With a person of color, it’s a job or strategy; with a white guy who claims to be from London, it’s a pleasure.

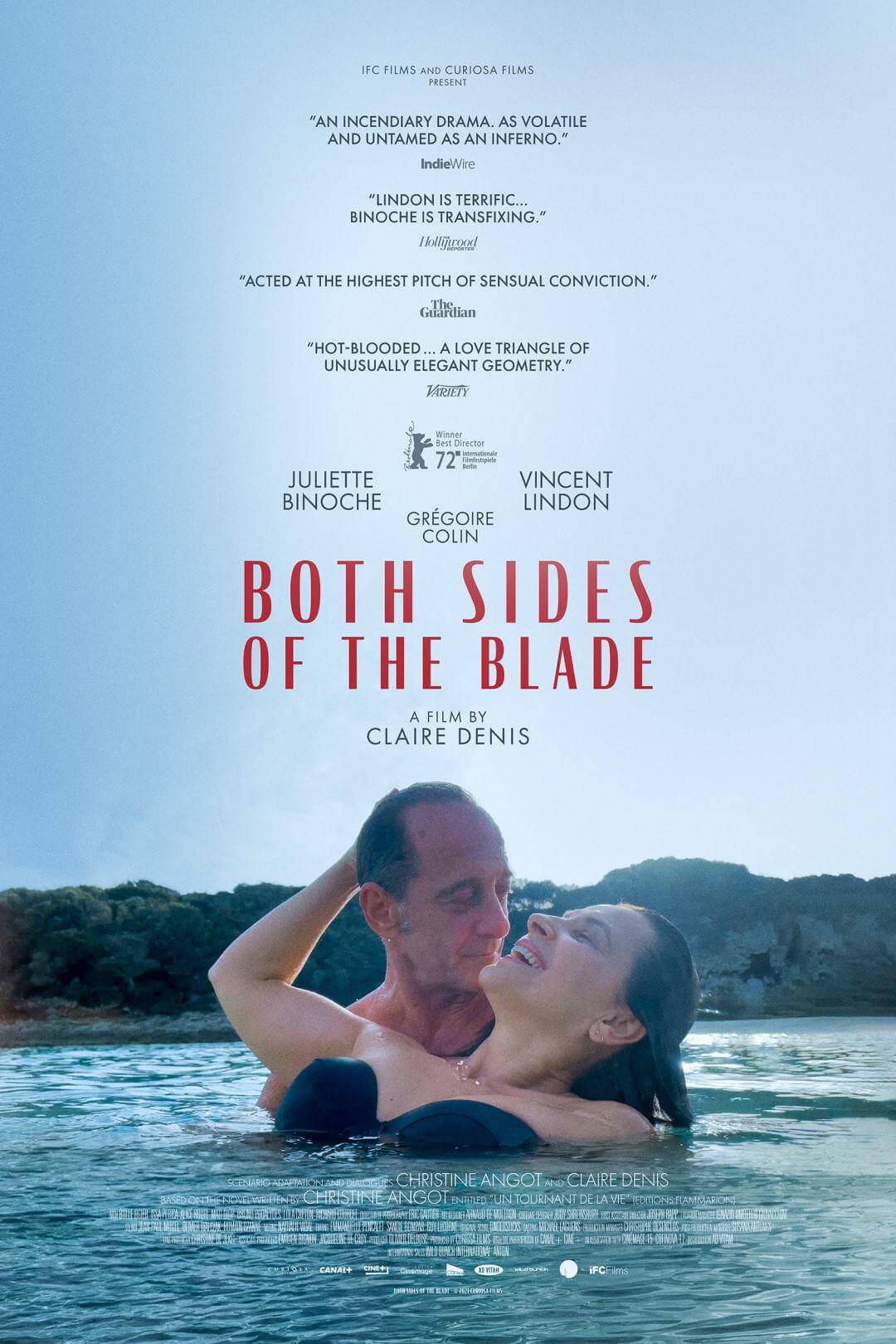

Their affair develops in the manner of Denis’ lovers in her 2002 film, Friday Night, which is to say, there’s no single moment when the two commit, but they flow into each other gradually in the director’s lyrical style. Stars at Noon doesn’t have the loose structure and impressionistic editing of many of her other films; there’s a more substantive moment-to-moment progression than, say, Both Sides of the Blade, her other film from 2022 about a troubled romance. Still, compared to any film outside of Denis’ filmography, it feels more like an atmosphere than a straightforward erotic thriller. Nevertheless, the director handles the sex scenes with intimacy and frankness, which implies how close Trish and Daniel become in a short time. Part of this is because Trish has unofficially turned into a sex worker; she even remarks about how her hotel room used to be rented out by the hour, and it has a secret door for johns to escape unseen. But Denis and cinematographer Éric Gautier, whose sharp eye usually accompanies Olivier Assayas films, capture moments between Trish and Daniel with the same nebulous clarity that defines their relationship, if that’s what it is.

Their affair develops in the manner of Denis’ lovers in her 2002 film, Friday Night, which is to say, there’s no single moment when the two commit, but they flow into each other gradually in the director’s lyrical style. Stars at Noon doesn’t have the loose structure and impressionistic editing of many of her other films; there’s a more substantive moment-to-moment progression than, say, Both Sides of the Blade, her other film from 2022 about a troubled romance. Still, compared to any film outside of Denis’ filmography, it feels more like an atmosphere than a straightforward erotic thriller. Nevertheless, the director handles the sex scenes with intimacy and frankness, which implies how close Trish and Daniel become in a short time. Part of this is because Trish has unofficially turned into a sex worker; she even remarks about how her hotel room used to be rented out by the hour, and it has a secret door for johns to escape unseen. But Denis and cinematographer Éric Gautier, whose sharp eye usually accompanies Olivier Assayas films, capture moments between Trish and Daniel with the same nebulous clarity that defines their relationship, if that’s what it is.

Stars at Noon is also a film about meddling in the “balance of power,” evading authorities, sneaking down alleyways, bribing corrupt officials, passing vaccination checks, and crossing borders. When Trish walks down the street, we see police carrying machine guns and hear the sound of helicopters overhead—an energy that recalls Costa-Gavras’ Missing (1982). There is talk of an upcoming election, which she implies will not happen, but Daniel is naive to this. The script, adapted by Denis and co-writers Andrew Litvack and Léa Mysius, becomes more straightforward in the second half once Daniel believes Trish that the Puerto Rican police are after him—a moment that causes his subtle smile to turn into slight dread. After that, their pathways begin to narrow. A cabbie ends up dead because of Daniel, a vehicle explodes, and soon there’s only one escape: a smarmy but logical CIA agent (Benny Safdie), flagged by his confidence and Hawaiian shirt, who offers Trish a ticket home to betray Daniel. The agent’s reasoning—“We’re two Americans, we’re friends”—is arrogant but somehow charismatic enough to infect Trish with doubt.

Every scene might recall one from a more conventional movie of this ilk, but Denis’ perspective lingers a little longer, looks a little different, and has been edited by Guy Lecorne with a curious rhythm that feels unfamiliar and hypnotic. The characters are just as moody and undefinable, like two cats who remain affectionate but are capable of betrayal. One moment, Trish refers to them as a honeymooning couple on the run; the next, she’s scheming for a plane ticket out of there. Daniel’s intentions remain even more suspect, since he evidently has a political agenda that serves his multinational master. Acting through this uncertainty, Qualley and Alwin have never been better, offering the kind of performances that few actors get to create inside Hollywood (where these two have spent most of their careers thus far). Here, they play their roles in a fog of seduction, genuine affection, and manipulation, and they’re brilliantly ambiguous. Are they using each other? For how long? And to what extent are their emotions real? If these questions remain difficult to answer by the end, it is perhaps enough that the two orbit around one another for the film’s 135-minute runtime, suggesting there’s some gravity between them.

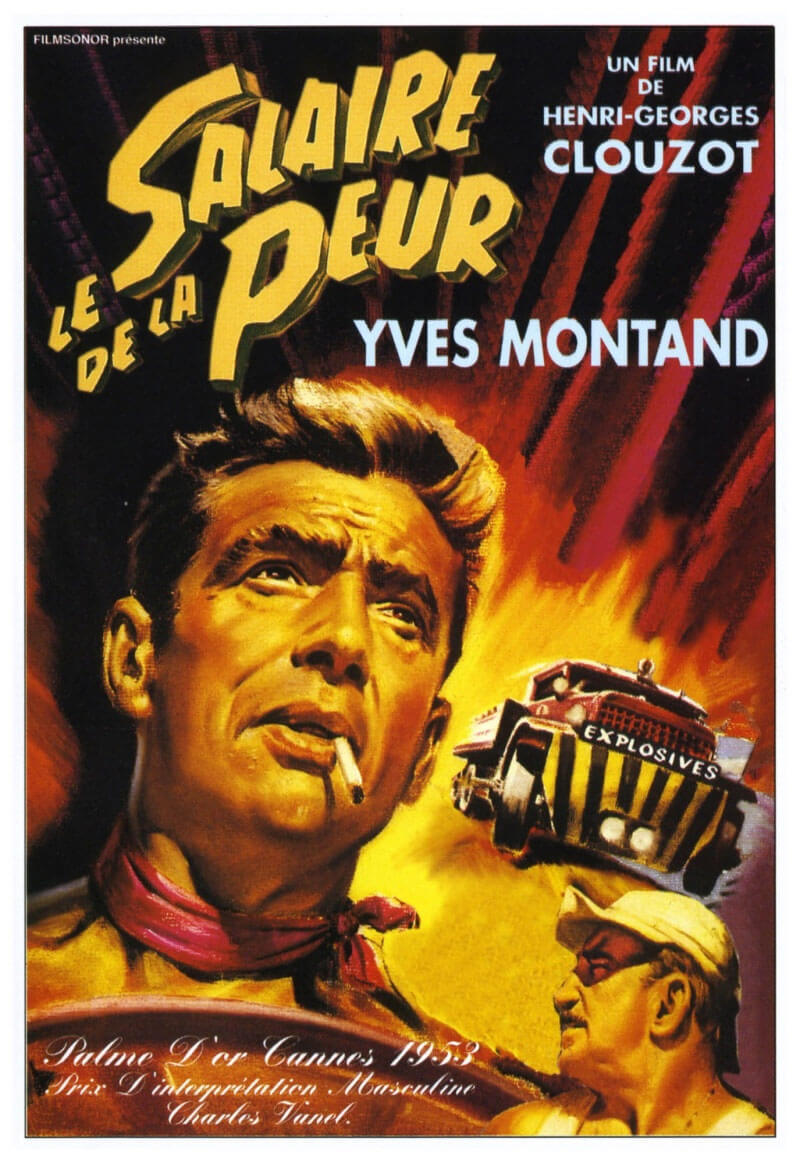

Denis spends much of Stars at Noon simply observing Trish and Daniel’s behavior—how they maneuver around each other, make love, and rely on each other. The jazzy, electronic-accented score by the Tindersticks, Denis’ regular collaborator, echoes the film’s improvisational momentum and loose structure. But it’s also a familiar kind of aura reminiscent of turn-of-the-century Steven Soderbergh films—above all, the tenuous romance from Out of Sight (1998) comes to mind, along with the free=flowing structure of The Limey (1999). Underneath the film’s atmospheric study of behavior, Denis continuously reminds us that these characters—who have reached rock bottom and might agree to drive a truck of nitroglycerin on a bumpy road à la The Wages of Fear (1953) if asked—benefit from their status as white people. Whether that means the CIA pulls strings for them, or Trish uses her status as an American to negotiate favors, these characters remain isolated and desperate yet also shielded from the worst of the local politics. Their sensual bond in an oppressed land is obscure and undefined, but their connection to the locals proves unquestionably detached.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review