Reader's Choice

Mountains May Depart

By Brian Eggert |

Mountains May Depart opens with star Zhao Tao cheerfully dancing to Pet Shop Boys’ “Go West” in an exercise class. It’s a lively and entertaining start to the film, regardless of the delightfully infectious song underscoring the film’s central theme all too precisely. Writer-director Jia Zhangke’s 2015 feature contains his usual investigation of China’s rapid globalization in a pointed narrative, deploying a glossy melodrama to create a moving portrait of his country’s embrace of Western capitalism. The result is not unlike the song: it’s effective despite its obviousness. Jia’s narrative unfolds over a quarter-century, broken into three distinct parts, each reflected by distinct formal flourishes, framed by not one but two leitmotifs—Pet Shop Boys’ 1993 cover of the Village People’s hit and Sally Yeh’s Canto-pop ballad “Take Care.” These structural pretenses and a shifting aspect ratio to represent three distinct points in time suggest Jia’s considerable complexity as a filmmaker. They also contribute to the film’s shift away from Jia’s purely aesthetic and philosophical ambitions. Mountains May Depart tells a sweeping story of history and change, with pronounced feelings and big emotional scenes. And while its dramatics present an unexpected deviation in Jia’s filmography, they’re also part of a mounting evolution.

Early in his career, in 2001, Jia Zhangke wrote a cinematic manifesto in response to the Fifth Generation filmmakers who had graduated from the Beijing Film Academy in 1982, such as Zhang Yimou (Raise the Red Lantern, 1991) and Chen Kaige (Farewell My Concubine, 1993). He wrote they had adopted “professional” techniques and produced large-scale historical dramas that valued spectacle over a “natural and realistic state.” Jia vowed that the “Age of Amateur Cinema Will Return,” and he yearned for the revival of “sincerity” over technique. In the years to come, Jia’s cinema would reflect that cause, adopting an experimental blend of documentary observation, slow-cinema immersion, digital camerawork, and elliptical narratives to explore a more radical form of cinema than the ballooning Chinese mainstream cinema. He resolved that “the most important thing is whether the film expresses the stuff of real life, whether it offers insights into reality.”

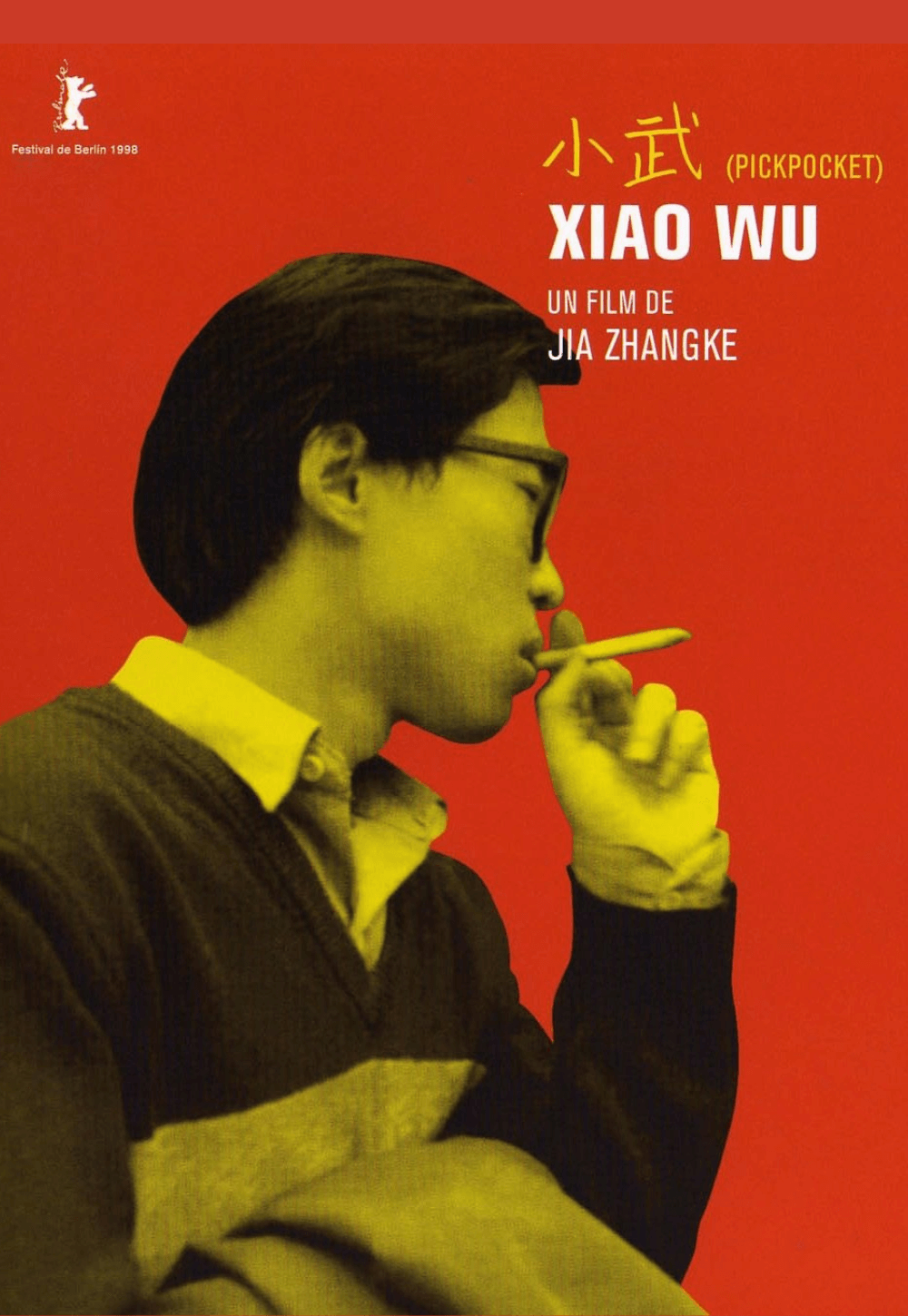

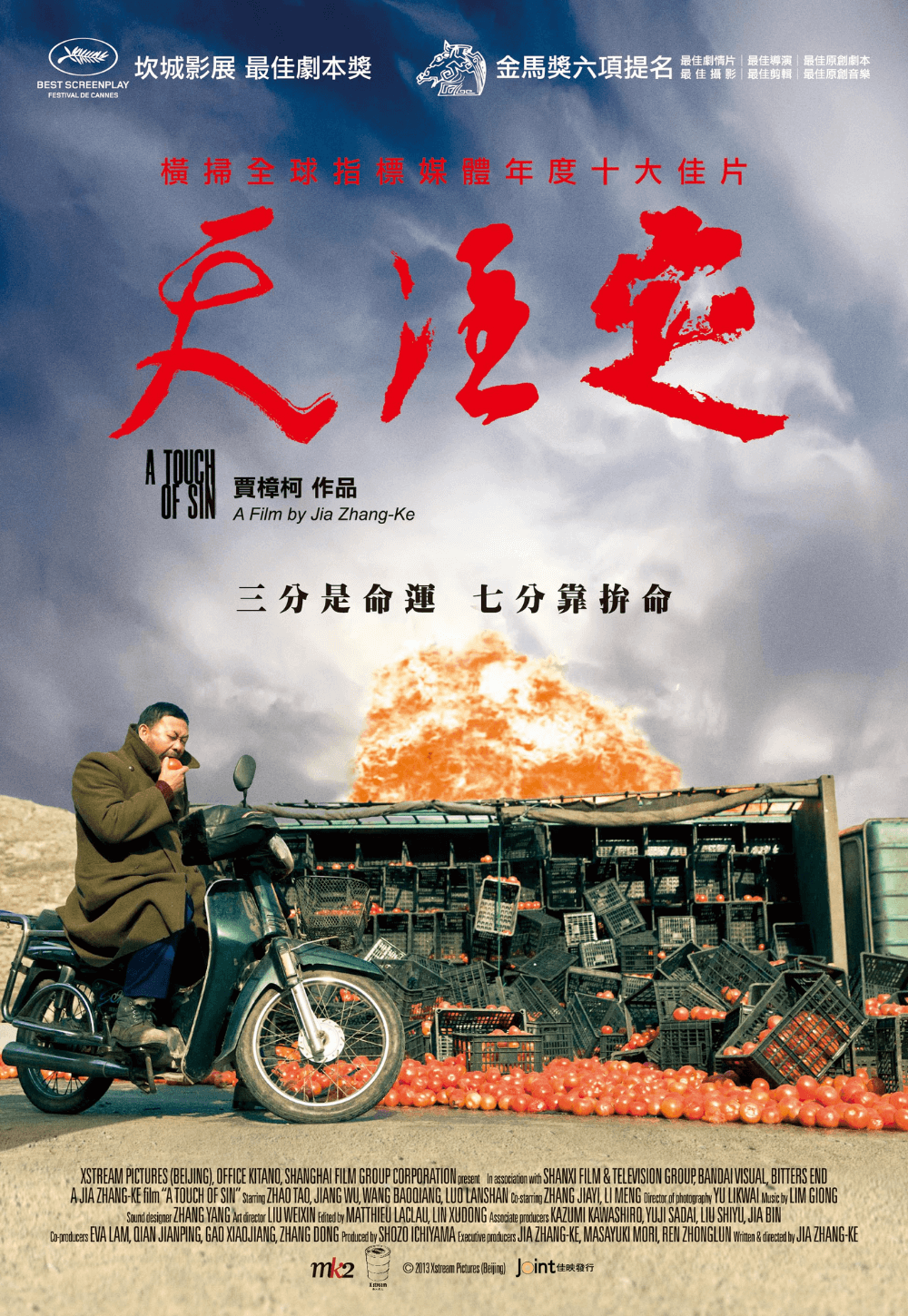

After his debut feature, Xiao Wu (1997), the Sixth Generation filmmaker continued his interest in avant-garde cinema in response to the previous generation. His underground features from Platform (2000) to Still Life (2006) were celebrated on the international festival circuit—and often unapproved for exhibition in mainland China—partly for his embrace of digital cameras and their aestheticized realism as the new medium of the twenty-first century. All the while, Jia also dabbled in short films and several documentary features, such as 24 City (2008), about an airplane engine factory that became a residential apartment building, and Swimming Out Till the Sea Turns Blue (2020), a look at China from the perspective of three writers who were each born a decade apart. Only recently has Jia earned international success with A Touch of Sin (2013) and Ash Is Purest White (2018), which arm accessible genres like a Trojan Horse to convey the director’s authorial themes and arthouse formal tendencies. But as Jia embraces genre, he also steps away from his manifesto’s intentions.

This is not to suggest that Jia, or any filmmaker, must adhere to an early career statement of cinematic principles. Certainly, similar aesthetic proclamations from the French New Wave’s denouncement of their film industry’s “Tradition of Quality” to the stripped-down Dogme 95 movement have seen directors pronounce lofty ambitions for their filmmaking only to break out of those boundaries later in their careers. François Truffaut made Fahrenheit 451 (1966) just a few years after The 400 Blows (1959), just as Lars von Trier made Antichrist (2019) two decades after The Idiots (1998). But Jia’s late-career adoption of genre has proved more successful elsewhere, despite his thoughtful application of form and scope.

Mountains May Depart takes place over three chapters, each with a distinct visual conceit: the 1999 segment appears in the boxy Academy aspect ratio, including documentary-style footage Jia shot in 1999 during the Chinese New Year celebrations. Then, the film transitions to 1.85:1 widescreen for the 2014 chapter, and saves the widest frame (2.39:1) for the final 2025 sequence. The choice reflects Jia’s recurrent theme of China’s fast-changing culture through form-follows-function technological advances. While Jia’s stylistic choices remain intentional and thoughtful, Mountains May Depart is less successful in its intended Sirkian melodrama, mainly due to some of the awkward dialogue, open-ended storylines, and performances, particularly in the final third.

In the 1999 segment set in Jia’s hometown of Fenyang—a 40-minute prologue, finally capped by the title card—Tao, played by the director’s wife and muse Zhao Tao, is pursued by two suitors: Liangzi (Liang Jin Dong), a kindly coal mine worker, and Jinsheng (Zhang Yi), known as “Boss Zhang” because he’s an up-and-coming capitalist. When Jinsheng buys the mine where Liangzi works, he offers Liangzi a promotion if he agrees to stop pursuing Tao. When Liangzi refuses, Jinsheng fires him. It’s anyone’s guess what Tao sees in this kind of petulant, money-is-power behavior, as Jinsheng proves inauthentic and even toxic: “You’re hurting me,” he tells her, pathetically, “because I care for you.” Nonetheless, Tao is charmed by his new Volkswagen and promising future, as many in her position might be. They marry and soon have a child named Daole. Jinsheng insists on nicknaming the child Dollar, vowing, “Daddy will make you lots of dollars.”

Many critics noted Jia’s clumsy dramaturgy and imagery in Mountains May Depart, though sometimes without cause. Jonathan Romney’s review in Film Comment complained about the on-the-nose quality of Dollar’s name, though the detail is not without precedent. Wayne Wang’s Life Is Cheap… But Toilet Paper Is Expensive (1989) featured a character named Money, for instance. And Chinese parents often select names related to prosperity and wealth for their children. If the name can be justified, not all of Jia’s choices feel so natural, particularly when it comes to Jinsheng, who plans out his next 15 years with Tao by the anticipated lifespan of their new puppy. “We’ll be turning 40 when it dies,” he remarks in a clear sign of his callousness. It’s no surprise that when the next chapter picks up in 2014, they’re divorced. Liangzi, who has since moved away from Fenyang and developed lung cancer from his years of coal mining, requires surgery. After they return to Fenyang to ask family and friends for a loan, his wife (Lu Liu) asks Tao for help, and she delivers the cash.

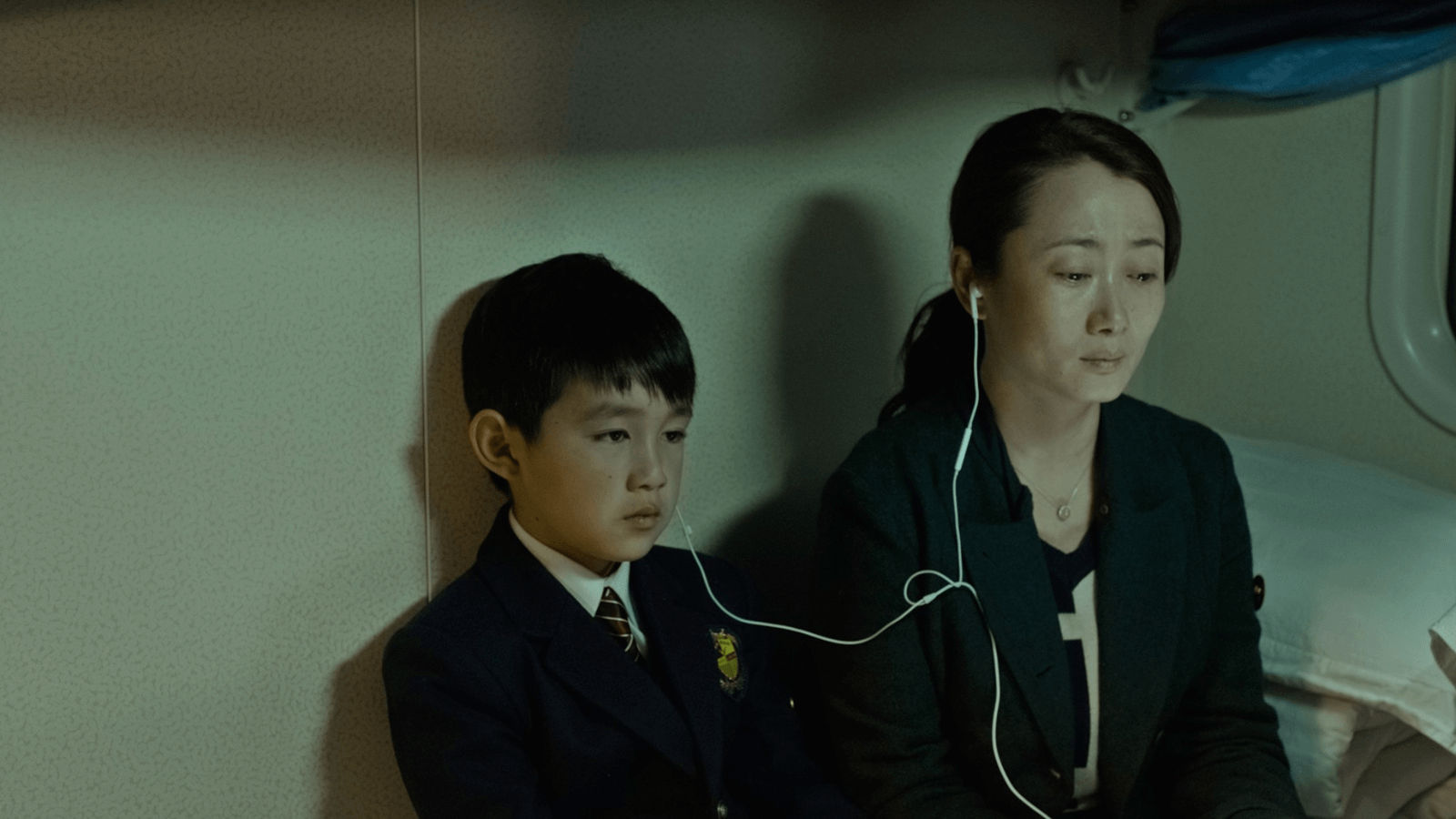

In a frustratingly dangling plot thread, Jia never clarifies if Liangzi received the surgery or survived, focusing instead on Tao and her fractured relationship with Dollar. The boy lives in Shanghai with Jinsheng, who has remarried and now calls himself Peter. Recognizing that Dollar will prosper more with his father, she says goodbye and remains in Fenyang. When the film picks up in 2025, Dollar (Dong Zijian) is now a young adult living in Australia, searching for an identity among other Chinese youths who have little knowledge of or have altogether forgotten their heritage—a common experience among his generation. This materializes when Dollar forms an Oedipal relationship with his teacher, Mia (Sylvia Chang), transferring his vague memories of his mother to another older woman. When Mia plays him “Take Care,” a tune Jinsheng played for Tao, and then Tao played for Dollar, he doesn’t remember why it sounds familiar. But the memory creates an emotional response that prompts him to explore a romance with Mia.

Set a decade in the future from when Jia made the picture, the last chapter suggests smart devices will become transparent and the US dollar will plummet—a practical prediction. Cinematographer Yu Lik Wai shoots the era with flat, metallic colors that lack the same vibrance of the film’s earlier segments in China. And while the relationship between Dollar and Mia proves tender, Dong’s acting and dialogue have a clunky, soap-opera quality to his strained emotions and lines about wanting “freedom” from his father’s expectations. But Jinsheng bemoans freedom, given Australia’s gun laws, complaining, “I can now own a pile of guns, but no one to fire them at. Freedom is bullshit!” Jinsheng has become rancorous, gun-obsessed, and generally displeased with Dollar’s eventual admission that he doesn’t want to attend college. Even so, Dollar and Mia plan to explore their roots on a trip (hers in Hong Kong and Toronto, his in Fenyang). Except, when a travel agent makes a faux pas about their age gap, he becomes flustered, and their relationship dissolves. “Time doesn’t change everything,” Mia tells Dollar, articulating the film’s central theme.

The title considers the impermanence of people, places, and cultures over time—when things change so fast, even mountains may disappear. Indeed, as part of its internal development, China has leveled mountains to erect cities and build bridges. But even as China has rapidly changed into a significant economic force since 1999, other aspects have remained steady. Jia returns to the image of a long-standing Fenyang pavilion and temple that goes unchanged for the film’s duration. Similarly, Tao, whose name means “waves,” makes traditional long dumplings by hand in all three periods, signifying that some individuals will preserve traditions while others, like Dollar, will forget. Jia’s interest lies in the interplay of past and present, a persistent entanglement in any culture that has become extreme in the last few decades of Chinese history. The notion is thoughtfully and movingly articulated by the final scene, which finds Tao, now aged, again dancing to Pet Shop Boys’ “Go West” against the backdrop of the Fenyang horizon that has not changed since 1999. In an ironic move, Tao remembers her past with a British synth-pop song about the future. This speaks to an irrevocably globalized, postmodern world.

Some, like Dollar, rush to the future to leave China behind, only to discover an interest in their heritage later. Others never move beyond tradition and are passed by, as hinted at when Jia doesn’t conclude Liangzi’s storyline. Tao, wonderfully performed by Zhao Tao, represents a melancholic figure abandoned by younger generations, embodying the conflict between the traditional and aspirationally modern in her spirited final dance to “Go West.” Although these symbolic purposes are readable, suggesting some are too quick to embrace change, while others are too dogged in their traditionalism, Mountains May Depart ultimately explores them in a melodramatic tone that Jia never quite masters. He’s better at understatement and arthouse ambiguity than larger-than-life feelings and romantic dialogue, and that’s most evident in the film’s progressive heightening of emotions that feel ever more artificial with each new chapter. Perhaps this is Jia’s commentary about a capitalistic world feeling out of touch, or maybe it’s the outcome of a filmmaker experimenting just outside his capacity.

(Note: This review was originally posted to DFR’s Patreon on March 26, 2025.)

Bibliography:

Frodon, Jean-Michel. The World of Jia Zhangke. Film Desk Books, 2021.

Jia Zhangke. Jia Zhangke Speaks Out: The Chinese Director’s Texts on Film. Bridge21 Publications, 2015.

Mello, Cecília. The Cinema of Jia Zhangke: Realism and Memory in Chinese Film. I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd, 2019.

Romney, Jonathan. “Film of the Week: Mountains May Depart.” Film Comment, 11 February 2016. https://www.filmcomment.com/blog/film-of-the-week-mountains-may-depart/. Accessed 22 March 2025.

Xiaoping, Wang. China in the Age of Global Capitalism: Jia Zhangke’s Filmic World. Routledge; 1st edition, 2019.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review