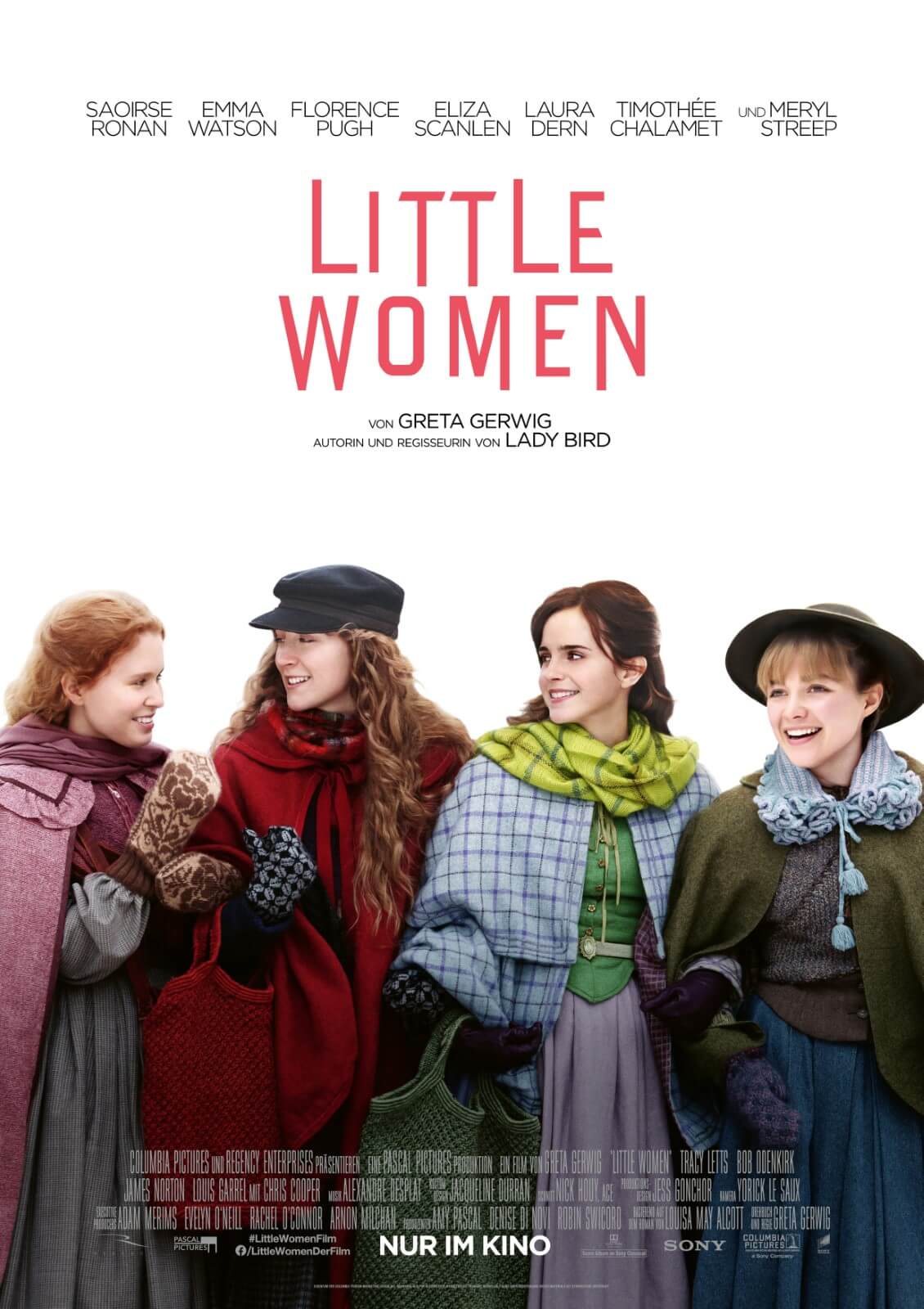

Misbehaviour

By Brian Eggert |

Misbehaviour is a pleasant movie about a feminist action against the 1970 Miss World competition in London, which brought global attention to the Women’s Liberation Movement. There’s a throwaway line in the movie that the televised Miss World event in 1969 earned more viewers than the Moon landing. That statistic seems unthinkable today, since these pageants have mostly disappeared from popular culture. The concept of women parading around on a stage and waving at cameras, while leering judges consider their measurements and score them on their appearance, feels backward and wrong. However, some of these competitions still exist for adults, so critics shouldn’t be surprised when children, evidenced in Cuties (2020), aspire to sexualize themselves and become the next pageant winner. Although it avoids the radicalism suggested by the title, Misbehaviour is simple and clear, offering an inspirational message that could serve young girls, or Intro to Women’s Studies classes, with a stirring example through its unabashedly mainstream presentation.

Keira Knightley plays Sally Alexander, a bourgeois Londoner who believes she can change the male-dominated academic establishment from within. A single parent with a traditionalist mother, Sally attends university, where her male peers talk over her, and her advisor calls her dissertation subject on female workers of “minority interest.” Fed up with the misogyny she encounters, Sally joins forces with Jo Robinson (Jesse Buckley), an activist from a women’s commune intent on disrupting the patriarchy. Their group plans to gain entrance to the Miss World event, which will be watched by millions the world over, and get eyes on their cause. Seedy pageant head Eric Morley (Rhys Ifans) is on alert, having heard of their plans to disrupt his “family entertainment show,” in which he treats “girls” like cattle. “Herd them up,” shouts Morely to his assistant, while his wife (Keeley Hawes) helps organize the event without question. Morley also goes to great lengths to secure a special guest appearance by Bob Hope (Greg Kinnear, behind a fake nose), whose infidelities and treatment of women have led to a rocky relationship with his wife (Lesley Manville, who wins the movie with a priceless, satisfied smile late in the proceedings). It’s an unflattering portrait of Hope, who kisses at women and makes lewd remarks to his new secretary—but also because Kinnear’s impersonation falters.

Screenwriters Gaby Chiappe and Rebecca Frayn were inspired by Miss World 1970: How I Entered a Pageant and Wound Up Making History, an autobiography by Jennifer Hosten, the crowned winner from Grenada. Gugu Mbatha-Raw plays her and, after her eventual victory, she faces Sally in an affecting moment that confronts the theme of intersectionality. Sally wants to protect her daughter from becoming another devalued beauty contestant; Jennifer wants the impoverished and marginalized children of her country to have the same opportunities as white women. To be sure, race and class play a vital role in Misbehaviour, but the complexities of these issues won’t be addressed with much detail. Elsewhere, Pearl Jansen (Loreece Harrison) becomes the first Black South African—dubbed “Africa South” to differentiate her from her white counterpart from “South Africa”—to participate in the pageant, a concession made by Eric Morely to appease the press who are critical of apartheid. At every turn, the women in the film are treated differently because they are women or women of color, and they demand equal and fair treatment. The screenplay presents this message without subtlety, but its sympathetic characters earn our emotional investment.

Philippa Lowthorpe directs with a light touch, rarely going beyond surface-level concerns. Mostly versed in television and one other feature (Swallows and Amazons, 2016), she delivers airy scenes occasionally rooted in convincing period detail and nostalgia, but always simple characterizations. Most of the contestants, for instance, prove one-note. Miss Sweden (Clara Rosager) and Miss United States (Suki Waterhouse) couldn’t be more stereotypical, the former cast as Bergmanesque and the latter in an Uncle Sam costume. Some story elements seem like rogue inclusions, such as the Grenada leader, who convinces Mrs. Morley to make him a judge. Did he somehow rig the competition for Jennifer? Who knows. With so many competing story strains, some of the subplots and actors cannot help but feel underutilized—Buckley above all. When she gave such a tour-de-force performance in this year’s I’m Thinking of Ending Things, it’s difficult to watch her in such a minor role, even though she lends the part presence to spare. Knightley and Raw, as ever, imbue their characters with weight beyond what was written for them.

Wrapped in a polished commercial package, the movie telegraphs its ideas for a general audience, offering nothing so unconventional or aesthetically rebelious that a more independent director may have made. It belongs on a list of movies—next to Suffragette (2015) or On the Basis of Sex (2018)—that aren’t likely to convert anyone to their cause, though they reinforce feminist maxims in approachable terms. Misbehaviour is also quite British, with its emotions reserved and proper compared to other, angrier examples of feminist activism. Two years earlier in New Jersey, the New York Radical Women led hundreds in a protest of the Miss America pageant; they even rented live sheep to demonstrate how the contestants were ordered like animals. In comparison, throwing flour bombs and pointing a squirt gun at Bob Hope seems relatively less impactful, but every statement builds on one another. While Misbehaviour boasts an impressive cast and just enough relatable frustration to warrant enjoying, the viewer could imagine a more rugged version of the same story. If nothing else, it shows how sometimes sustained protest is the only way to effect sociopolitical change, which remains a vital lesson even today.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review