Highest 2 Lowest

By Brian Eggert |

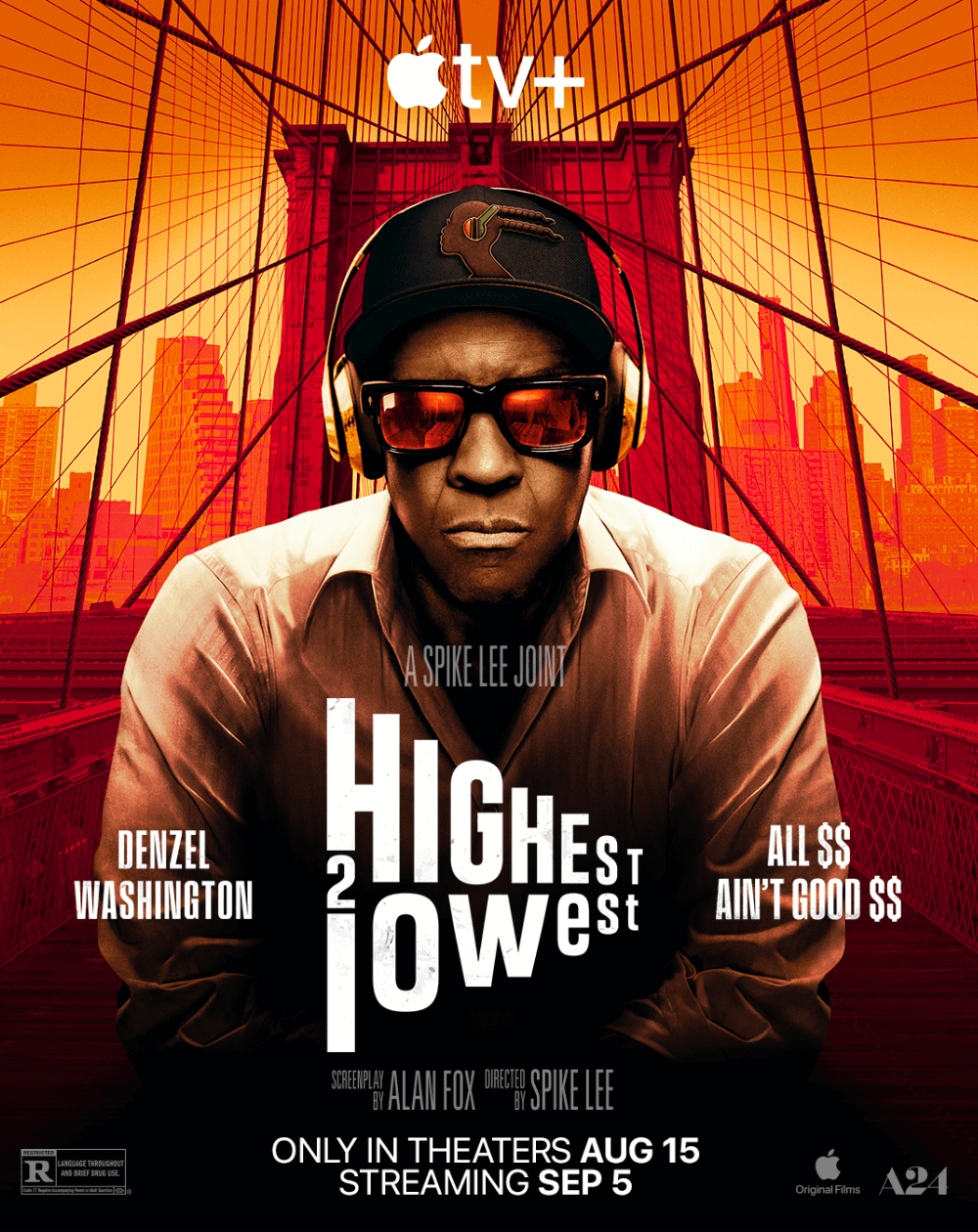

Spike Lee’s Highest 2 Lowest arrives at a fitting time. American capitalism has never been more unbridled, and the importance of art has never been more diminished. Corporations and even creatives have embraced artificial intelligence, calling it a “tool” of convenience and cost savings. Venerable institutions of higher education have either deprioritized or eliminated their humanities disciplines in favor of degrees that support high-paying careers. Debates about banning literature and other creative works have plagued schools, libraries, and community centers. Hell, even film criticism has seen better days. Major outlets continue to reassign or eliminate their critics more than ever before, prioritizing the attention garnered by bite-sized influencer reaction videos over the cultural value of criticism. Some of these developments aren’t surprising. Generally, Americans value money over art and ease over challenges. They view success not by the moral choices you make or the legacy you leave; you’re a success when you become rich and famous, regardless of how. Money talks, and those in power find what art has to say secondary to the revenue it produces. After all, many conversations about whether Highest 2 Lowest was a success won’t center on what the film had to say but on how much money it made. Yet, Lee’s film considers an alternative: “All money ain’t good money.”

With Highest 2 Lowest, Lee rethinks Akira Kurosawa’s kidnapping thriller High and Low (1963), which was based on Ed McBain’s 1959 crime novel King’s Ransom. Less a remake of the Japanese classic than a new adaptation that aligns with its director’s sensibilities, Lee’s film refocuses its attention on an entirely different thematic concern. In Kurosawa’s film, the story involves a shoe executive who, on the cusp of a risky venture to seize power and improve the quality of his company’s output, must reluctantly sacrifice the capital he set aside for his deal to pay the ransom for a kidnapped child. Kurosawa defines the kidnapper and the executive not by their classes—the executive in a house on hill, the kidnapper in the city below—but by the choices they make, which, regardless of their dichotomous class and privilege, carry moral implications. Whereas Kurosawa’s diptych-structured film alternates between a stage drama and a gritty docu-style procedural, Lee’s version, written by Alan Fox, deviates from the material’s genre focus. In Highest 2 Lowest, it’s less about the cops catching the bad guy and recovering the loot than an existential awakening for the executive, whose internal debate about what he values more, art or commerce, drives the narrative.

In the opening sequence, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’” plays with what becomes ironic optimism, set against images of the lavish apartment buildings on the Brooklyn side of the East River. Among them is the penthouse of David King (Denzel Washington), better known as “King David”—a famed music producer renowned for having “the best ears in the business.” His struggling company, Stackin’ Hits Records, plans to sell to a conglomerate, which would likely “squeeze every drop of Black culture and integrity” out of its music catalog and liquidate the company in a couple of years if it failed to make a profit. However, David has just finalized plans to reorganize his assets to regain control. “It’s a beautiful day,” says David. However, his wife, Pam (Ilfenesh Hadera), and 17-year-old son, Trey (Aubrey Joseph), question his focus on the business over his passions: listening to music, discovering new artists, and spending more time with his family. Early scenes suggest that David has diverged from the path of celebrating Black music and culture, and despite his efforts to reassert himself within the corporation, the damage is already done.

After some shrewd negotiating to secure the future of Stackin’ Hits, David receives a call: A kidnapper has taken Trey, and in exchange, they want $17.5 million in Swiss francs. Police arrive at the King penthouse to oversee the investigation. John Douglas Thompson, LaChanze, and Dean Winters play the detectives, and they’re immediately drawn to David’s longtime friend and assistant, Paul (Jeffrey Wright), who recently completed his parole. Paul has a son, the same age as Trey, named Kyle (Elijah Wright, Jeffrey’s son), who is David’s godson. As it turns out, the kidnappers took Kyle, not Trey. Whereas David was ready to sacrifice his money and plans for Stackin’ Hits to save his son, he doesn’t feel the same responsibility for Paul’s son. The scenes around David’s choice crackle with dramatic energy and are among the most powerful in the film. Unable to look at his friend, David closes his eyes out of shame and resorts to business-speak when he informs Paul. Afterward, Trey confronts his father over this cruel decision: “The man with the best ears in the business, but the coldest heart,” he observes—a statement that sends David spiraling into anger and tears over how he has betrayed his friend and lost the respect of his family. It’s also some of Washington’s best acting to date, conveying how David is pulled between art and commerce, bringing him to tears.

Convinced by his family and worried that not paying might result in online backlash, David finally agrees to the demands. Rather than amplifying the tension with the usual high-energy score and intense tone, Lee approaches the ransom delivery and subsequent chase sequence by cross-cutting between the drop-off and a Puerto Rican Day Parade, filled with music and dancing in the streets. David must take a subway loaded with intense Yankees fans while receiving instructions from the kidnapper by phone, all while detectives follow, eventually leading to a dizzying, highly coordinated system of handoffs. The police lose the money in the shuffle. From here, Lee deviates from High and Low. Whereas Kurosawa turned his film over to the police investigation while the executive took a passive role, Lee has David pursuing the kidnapper, not with the help of the police but with Paul—and set to James Brown’s “The Payback.” It’s not purely about taking the law into his own hands à la Death Wish (1974), however. The cops dismiss David’s evidence, and he decides to move when they won’t.

The tone throughout is not one of relentless pressure, though it is suspenseful. Instead, Highest 2 Lowest takes a novel-like approach, allowing for fluctuations in mood and meaning. This is classic Lee. Rather than merely reinforcing the narrative’s genre vibes, composer Howard Drossin, a regular collaborator with Lee, supplies a piano score that introduces operatic and lyrical notes into the film’s harmonious dissonance. Sequences like the drop-off, with seemingly disparate elements—the thrill of the chase, the hometown Yankee pride, and the chill sounds coming from the Puerto Rican festival—often prompt other reviewers to describe Lee’s work as “messy” or “disorganized.” But it’s not as though the filmmaker, with over 25 features to his credit and a tenured professorship at NYU, where he graduated with a Master’s degree and now teaches about film, has no method to the perceived madness. Lee, similar to Ken Russell and Bong Joon-ho, is a master at merging contrasts into a dialectical synthesis.

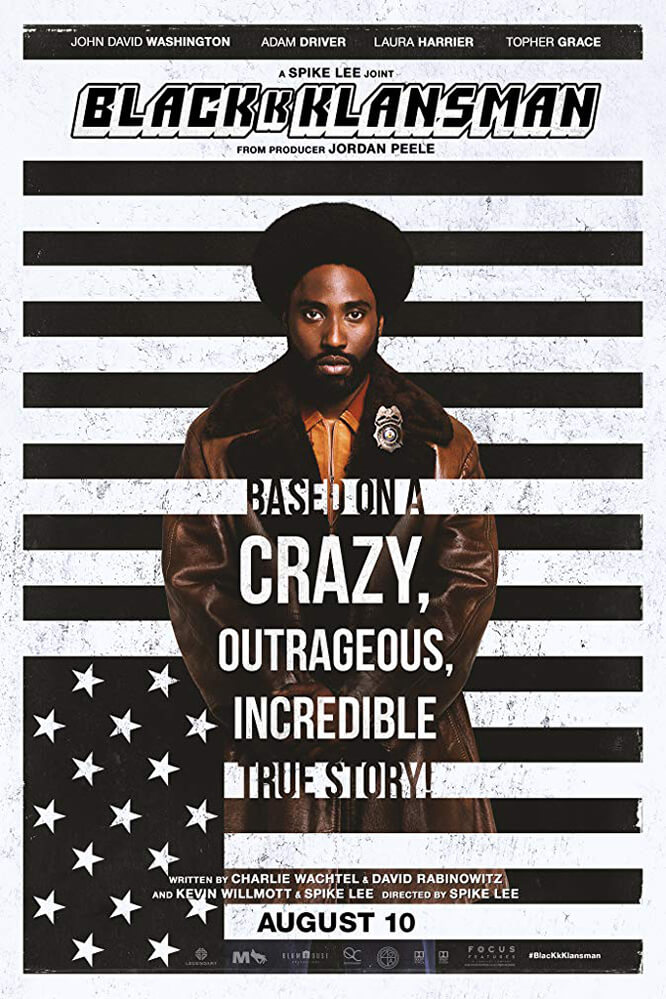

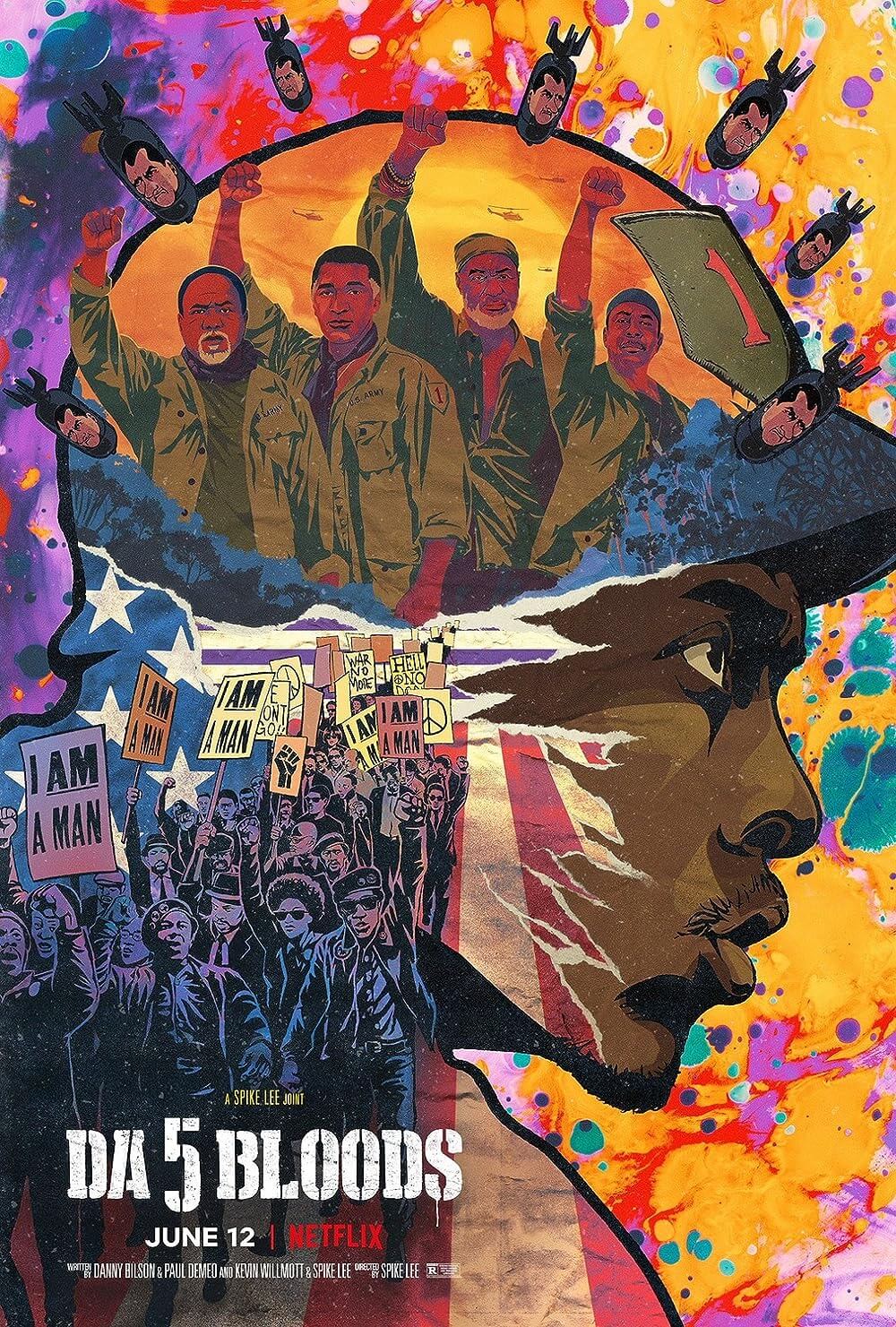

Lee, 68, continues his streak of films that use genre to explore Black culture, artistic expression, American history, and today’s sociopolitical conversations. Much like the mode of Greek drama in Chi-Raq (2015), the true crime yarn BlacKkKlansman (2018), and the Vietnam War actioner Da 5 Bloods (2020), Highest 2 Lowest defies its label as a kidnapping thriller. Every frame is “a Spike Lee joint,” evidenced in the director’s palpable love of New York, how his characters speak directly into the camera, and his signature double dolly shots. Lee’s personal signatures—including in-jokes about co-distributor A24 and Jeffrey Wright’s performance in Basquiat (1996)—defy realism in favor of expressive and multilayered filmmaking. Yet, his asides and tangents never disrupt the story’s momentum; instead, they enhance the personality and humanity on display, particularly among the actors. This is the fifth film Lee has made with Washington, the first since Inside Man (2006), and it’s only bettered by Malcolm X (1992). As ever, Lee directs outstanding performances. Besides Washington, Jeffrey Wright is terrific, and A$AP Rocky makes a memorable contribution as the kidnapper, an aspiring rapper named Yung Felon.

Lee also reminds his audience what a sharp technical director he is, delivering, with his frequent cinematographer Matthew Libatique, one stunning composition after another. Watch the scene when David tells Paul that he won’t pay the ransom: The camera inside King’s apartment looks out over the balcony, where the two men stand before the illuminated Manhattan skyline in the distance. A golden, globular, cloud-like ceiling light from inside is reflected in the window, creating a glimmering spectre that appears to hover above the two men and the city—as though the cloud that hangs over their friendship, and New York, is money. Elsewhere, memory-images of David’s heyday as a producer, before he became so money-minded, appear on celluloid—evoking a more idealized period on a preferable cinematic medium, used at a time when aesthetics mattered more, or at least as much, as the revenue they produced. Near the finale, two sequences frame David and Yung Felon opposite each other, with glass between them in a recording studio and later in a prison visitation room. Lee was inspired by a similar sequence from High and Low, repurposing the image here to visualize what separates the two men.

Like many of his generation—including Trey, who eventually aligns more with his father as the story progresses—Yung Felon believes that “Attention is the only currency.” In the wake of the kidnapping, Yung Felon even attempts to broker a deal with David, citing his newfound popularity. But for Lee and David, creating art is about more than merely followers, fame, and a payday at any cost. Just as artificial intelligence cannot imbue music or cinema with artistic soul, authentic art does not come from the desire to be popular or commercially successful. In the end, King resolves to build a new empire rooted in family ownership, which Richard Brody in The New Yorker calls “fundamentally conservative”—a term he uses without pejorative connotations. While a conservative emphasis on family and tradition in the form of Black culture indeed emerges in the finale, Highest 2 Lowest censures the soulless markets that prioritize the pursuit of money and fame above all else, leaving genuine artists and cultural enrichment by the wayside. David, and by extension Lee, confronts the audience with the notion that making art shouldn’t be about making money, at least not exclusively. Lee’s argument is more nuanced than a conservative or liberal label suggests.

Perhaps unintentionally, Lee evokes the Coen brothers’ Fargo (1996), when Marge Gunderson tells a remorseless killer, “There’s more to life than a little money, you know. Don’tcha know that?” Applied to the music industry, the many millions earned by Elvis, The Beatles, Whitney Houston, and other past superstars isn’t what solidified their legacies; it’s their creative output and enduring impact on the culture. Yung Felon and many in David’s business cannot imagine anything more important than money. In his perfectly imperfect approach, Lee answers this with an epilogue, featuring Aiyana-Lee Anderson as an up-and-coming Brooklyn musician named Sula, which showcases how passion and creativity can lead to financial success. Even if they don’t, artistic pursuits have their own rewards, whereas solely financial pursuits rot humanity. Lee’s refrain that “All money ain’t good money” punctuates not only the film but this moment, where a vast portion of America has sold itself to billionaires for a few financial perks. At once specific and universal, timely and evergreen, Highest 2 Lowest is one of the year’s best films and one of Lee’s most passionate statements about the value of art.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review