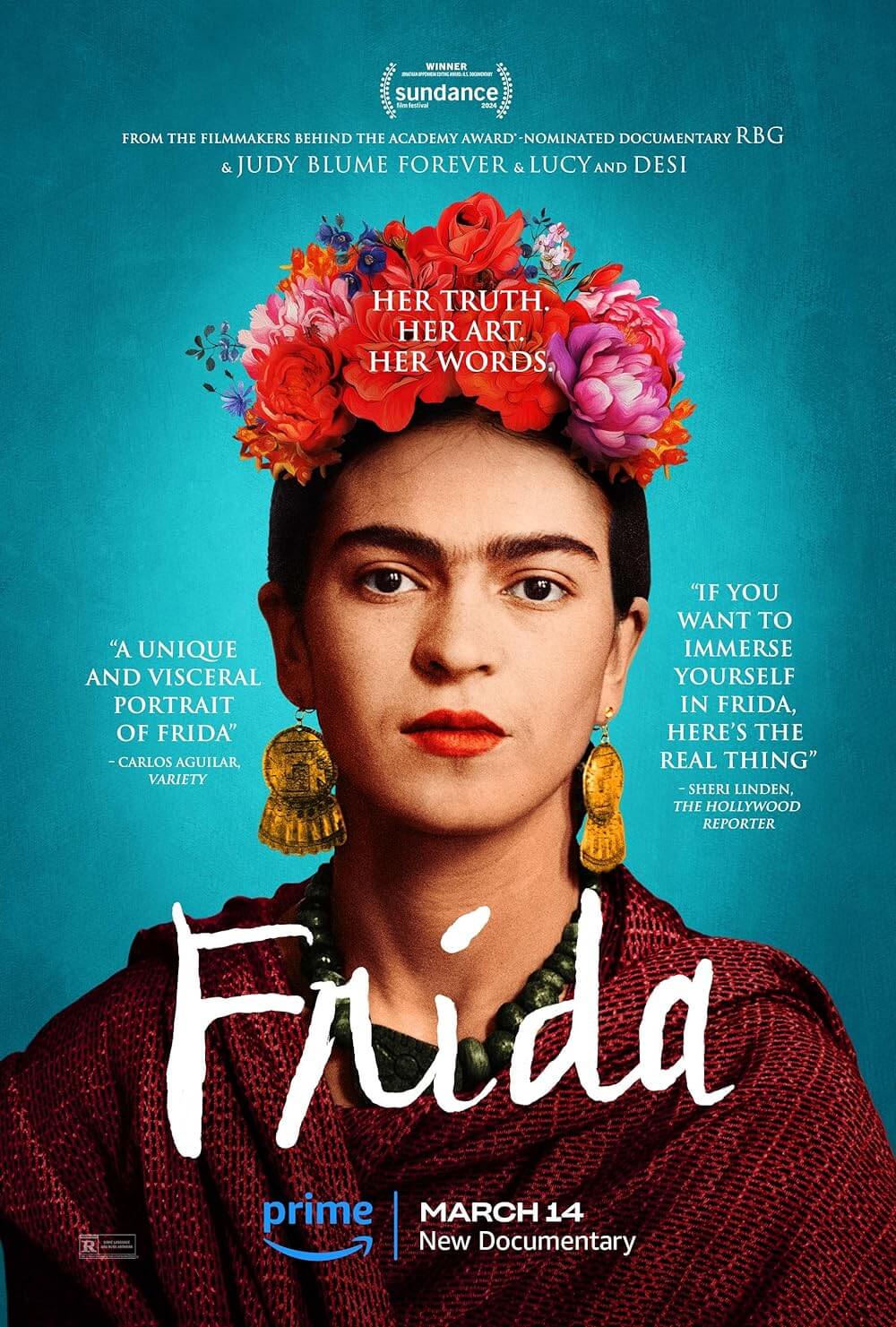

Frida

By Brian Eggert |

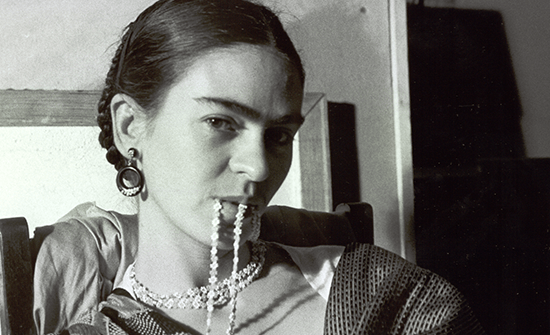

Documentary as a format has become stale. With the advent of the streaming documentary, the non-fictional film hasn’t grown or experimented much. Their presentation relies on the same few tricks of the trade, including talking head interviews, graphical visual aids, fly-on-a-wall camerawork, intrusive hosts who lead the story, and personal investigations. In most cases, a documentary’s form recedes, becoming almost invisible and certainly not at the front of the viewer’s mind, thereby allowing the subject matter to take precedence. To find one trying something outside of the norm is rare. Perhaps that’s why Frida feels so novel within this genre unto itself. Directed by Carla Gutierrez and released on Amazon’s Prime Video streaming service, the film draws from letters and diary entries left by Mexican painter Frida Khalo and those close to her. It then visualizes these writings using a multitude of sources, including beautifully animated versions of Kahlo’s paintings, to create a meaningful connection with its subject.

Frida Kahlo has been well-represented in narrative film and documentaries. Most famously, Julie Taymor made an Oscar-winning feature in 2002 starring Salma Hayek. Typical of this sort of biopic, that film plays like a highlight reel of the artist’s life. Still, it’s a thoughtfully acted and handsomely staged production, with a memorable cast including Alfred Molina as Kahlo’s twice-married artist husband, the philandering Diego Rivera. Several documentaries in this century alone—The Life and Times of Frida Kahlo (2005), Frida. Viva la Vida (2019), and Frida Kahlo (2020), to list a few—have taken distinct approaches to showcasing her life and work. Most rely on art historians and biographers to consider the intersection of Kahlo’s life and her art, since, more than most artists from this era, her work is inextricable from the events in her life. “In my life, I’ve only painted the honest expression of myself,” she wrote, “to say what I couldn’t in any other way.”

Gutierrez’s doc, produced in part by Ron Howard and Brian Grazer’s Imagine Entertainment, deploys no talking heads or experts to tell the viewer about Kahlo. The film doesn’t have narration in the traditional sense. Instead, voice actors read from the writings of Kahlo and those close to her, while animators Sofía Inés Cázares and Renata Galindo bring Kahlo’s paintings to life, illustrating how her inner thoughts, anxieties, and passions were expressed through her creative output. There could hardly be more potent or richly conceived visual aids for a film, given Kahlo’s tendency to conjure emotions with graphic, dreamlike imagery rooted in self-portraiture, Nature, and the subconscious. Throughout Frida, Gutierrez and editor David Teague weave black-and-white archival footage, photographs, and animated renderings of Kahlo’s paintings to create a sense of intimacy. Fernanda Echevarría del Rivero voices Kahlo’s passages, giving emotional, convincing readings from the artist’s personal diaries, which reveal her uninhibited remarks about personal expression, sex, marriage, pain, and creation.

Starting in 1910, when Kahlo was a child who questioned everything, the doc establishes how her father was a photographer, atheist, and committed reader who influenced her later sense of defiance. She was drawn to stories of Emiliano Zapata’s revolution and admired his coraje (courage) and his willingness to respond violently to injustice. In 1922, for instance, she joined a group of young upstarts known as the Los Cachuchas and dressed in typically male clothes in school, earning a reputation as a nonconformist. Of course, the most formative moment in her life from this period is the bus accident that sent a handrail through her “like a sword through a bull,” she writes, leaving her in traction for a year. It would be a constant source of physical pain and inspiration for her work. After the bus incident left Kahlo with a need to be “productive with the health I have left,” she denies herself nothing. “I think everything that gives pleasure is good,” she affirms. She then met mural painter Diego Rivera when she was 18, and he wooed her with his appreciation of her talent.

Starting in 1910, when Kahlo was a child who questioned everything, the doc establishes how her father was a photographer, atheist, and committed reader who influenced her later sense of defiance. She was drawn to stories of Emiliano Zapata’s revolution and admired his coraje (courage) and his willingness to respond violently to injustice. In 1922, for instance, she joined a group of young upstarts known as the Los Cachuchas and dressed in typically male clothes in school, earning a reputation as a nonconformist. Of course, the most formative moment in her life from this period is the bus accident that sent a handrail through her “like a sword through a bull,” she writes, leaving her in traction for a year. It would be a constant source of physical pain and inspiration for her work. After the bus incident left Kahlo with a need to be “productive with the health I have left,” she denies herself nothing. “I think everything that gives pleasure is good,” she affirms. She then met mural painter Diego Rivera when she was 18, and he wooed her with his appreciation of her talent.

What comes through in Frida is her absolute individuality and refusal to conform, even within artistic circles. When she marries Rivera—for the first time—in 1929, she’s exposed to a world of artists and high-class elites. She travels with him to New York in 1931 to aid him in painting the later-destroyed Man at the Crossroads mural for Rockefeller Center, and Kahlo can only remark on the “stupid lives” of high society. She even liberates herself from Rivera after 10 years, conflicted and jealous about his unfaithfulness, and shattered after multiple miscarriages. She’s not interested in being part of any group, despite her Communist ties over the years, not even the European surrealist artists with whom she’s often associated. Surrealist André Breton helps her with exhibitions of her work and admires how she developed into a surrealist without knowing the foundational ideas of the movement. Even so, she remains an outsider and rejects the bourgeois notions of art in Breton’s circles.

Gutierrez portrays Kahlo as an artist who draws from within, not from any political movement or artistic circles. While so many see her as a diminutive woman in a man’s world—Diego and others call her “little girl” and “little Frida” in their writings—Kahlo refuses to play any such role, and there was nothing “little” about her personality or paintings. She resolves to paint herself, regardless of whether the paintings sell, because personal expression is what she values. “I paint myself because it’s what I know best,” she writes. In both form and function, Frida plays like a firsthand account of the artist’s life. It’s the closest a documentary can get to Kahlo’s method of expression through self-portraiture, relying on her words and images to tell her story. What could be more fitting for this incomparable artist?

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review