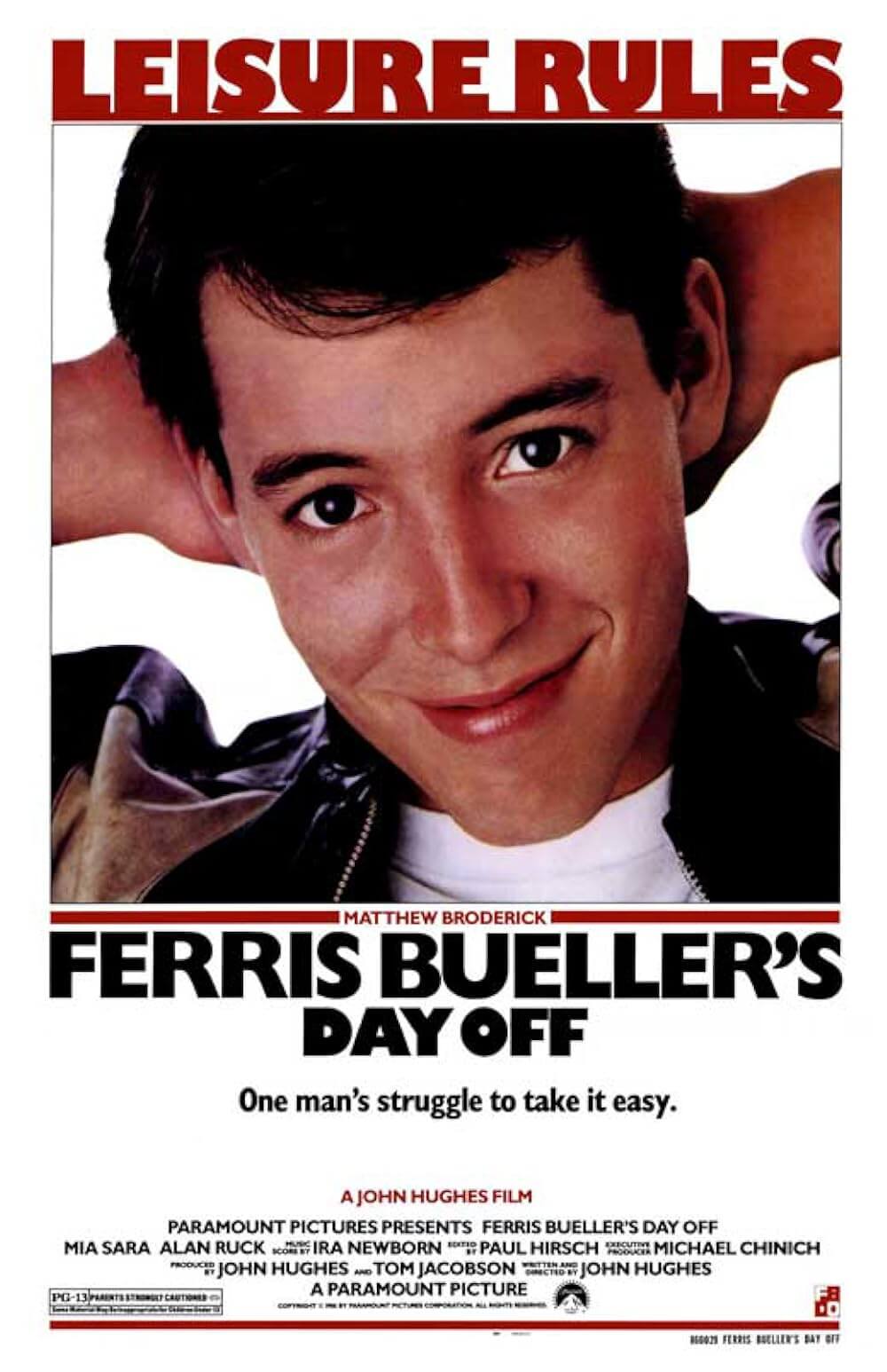

Ferris Bueller’s Day Off

By Brian Eggert |

More than any other quotable line in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off—more even than its bookend line, “Life moves pretty fast. If you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.”—the one that sticks the most is “You’re not dying, you just can’t think of anything good to do.” After faking out his parents to stay home sick from school, Matthew Broderick’s Ferris Bueller calls his best friend Cameron Frye (Alan Ruck) because Ferris doesn’t have a car, and he tells Cameron, who’s sickly and depressive, to come pick him up. They argue about it. In bed and surrounded by pill bottles and tissues, Cameron hangs up and says to himself, “I’m dying.” Ferris knows his friend well, calls back and tells him that, by and large, his sickness is all in his head, and that he’s just bored. Out of sheer irritation, Cameron finally resolves to get up and chauffer Ferris. The line itself is significant because it summarizes the entire film, which is an escape into the big city less about Ferris Bueller skipping school than demonstrating for Cameron how to move beyond his troubling home environment and, for a change, truly live.

John Hughes’ iconic 1986 film has been so consecrated into our pop-culture iconography that it’s easy to forget what a joyous, thoughtful celebration of life it happens to be. And what’s more, how accurately it depicts that crucial point in teendom when you realize that in order to live life the way you want to, you might have to break a few rules. Indeed, time has been good to Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and has transformed the picture into a cult unto itself. It’s always playing somewhere on television, quotable by everyone born in the last forty years, and remains so popular that it’s almost become a cliché. Regurgitating the plot for this assessment would be pointless—everyone knows it by heart. However, reviews at the time of its release criticized its flawless hero as incapable of being bested and questioned Hughes’ use of bored, upper-middle-class teens as subjects of uncertainty. More to the point, they criticized Ferris himself, his mission for his day off, and his lack of vulnerability through the course of the film. Patrick Goldstein of the Los Angeles Times wrote that Hughes made Ferris “so smug and invincible that he doesn’t give us any chance to root for him.”

But Broderick was perfectly cast as Ferris, his large brown eyes and genuine smile evoke a needed sense of trust, as opposed to what might otherwise be justified suspicion. After all, Ferris Bueller skips school, hacks school records (he’s a computer whiz without being one of the nerds from Hughes’ Weird Science, as the computer-savvy often were in the 1980s), performs complicated favors for everyone in his small town, and doesn’t find education particularly important (on his European Socialism exam he observes “I’m not European. I don’t plan on being European. So who gives a crap if they’re socialists? They could be fascist anarchists, it still doesn’t change the fact that I don’t own a car.”). For all intents and purposes, he’s a juvenile delinquent. He gets people out of summer school, he helps out druggies like Charlie Sheen’s punk-rocker character (who recommends Ferris’ skills to Jeanie, Ferris’ sister played by Jennifer Grey), and he’s beloved by all as a “righteous dude”. When word breaks out that he’s sick, the whole town—including the police department—rallies a “Save Ferris” campaign. He’s clearly performing kindnesses for everyone as friend and even mentor, and as a result, he’s praised, confident without being haughty, and enlightened enough to know he’s in a movie (he breaks the 4th wall).

But Broderick was perfectly cast as Ferris, his large brown eyes and genuine smile evoke a needed sense of trust, as opposed to what might otherwise be justified suspicion. After all, Ferris Bueller skips school, hacks school records (he’s a computer whiz without being one of the nerds from Hughes’ Weird Science, as the computer-savvy often were in the 1980s), performs complicated favors for everyone in his small town, and doesn’t find education particularly important (on his European Socialism exam he observes “I’m not European. I don’t plan on being European. So who gives a crap if they’re socialists? They could be fascist anarchists, it still doesn’t change the fact that I don’t own a car.”). For all intents and purposes, he’s a juvenile delinquent. He gets people out of summer school, he helps out druggies like Charlie Sheen’s punk-rocker character (who recommends Ferris’ skills to Jeanie, Ferris’ sister played by Jennifer Grey), and he’s beloved by all as a “righteous dude”. When word breaks out that he’s sick, the whole town—including the police department—rallies a “Save Ferris” campaign. He’s clearly performing kindnesses for everyone as friend and even mentor, and as a result, he’s praised, confident without being haughty, and enlightened enough to know he’s in a movie (he breaks the 4th wall).

Ferris’ life, it seems, is effortless, and could be described as one big day off. In that respect, the film is less about Ferris’ skipping school for a day (which he’s done nine times) and more about Cameron getting a day off—the events of the film a benevolent gift from one best friend to another, to crack Cameron out of his ongoing funk. Ferris describes Cameron as “so tight that if you stuck a lump of coal up his ass, in two weeks, you’d have a diamond.” Cameron remains opposed to every one of Ferris’ ideas. He’s tightly wound, his pants held up by suspenders and a belt (he doesn’t trust those pants!), and he feels better when he’s sick. And yet, Ferris pushes Cameron, and tries to break him out of his shell throughout the film: he chooses Cameron’s father’s prized Ferrari (an ultra-rare 250 GT California Spyder convertible) for their day’s joyride; he demands Cameron call the Dean of Students Ed Rooney (Jeffrey Jones) to get Ferris’ girlfriend Sloane (Mia Sara) out of school by pretending to be her father; he puts Cameron in situations where he’s forced to confront his apprehensions. Ferris tries to show Cameron the time of his life. Despite these palpable signs, Gene Siskel remarked that “If this element of Ferris as teacher had been scattered more frequently throughout the movie, it would be a better film. The picture should be re-edited.” Could this Ferris the teacher element be more evident without it being spelled out? Either Ferris is the worst friend someone like Cameron could have or the best.

Ferris’ idea of an escape becomes a journey into downtown Chicago. Hughes, whose teen years were spent growing up in Chicago’s suburbs, uses the second act portion of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off as a celebration of the city, a brief metropolitan love letter. With Sloane (a somewhat useless character) in tow, Ferris and Cameron visit various Chicago landmarks, including the Sears Tower, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, a Cubs game at Wrigley Field, the glorious Art Institute of Chicago, and the annual Von Steuben Day Parade. Though designed as a getaway, their day becomes a kind of spiritual awakening and vacation for Cameron (as Bill Murray’s character in What About Bob? said, “Take a vacation… from my problems!”). First, he’s swept up by Georges Seurat’s pointillist masterwork A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, where he identifies with the image of a little girl. As he looks at her, the shot gets closer and closer; the pointillism style is designed so that, as you look closer, shape and form disappear. Before long, Cameron sees nothing. Here, Cameron recognizes that he’s not living in his current state; the more you look at him, the less you see. Only later, when he inadvertently “kills” his father’s Ferrari, does he acknowledge that “I’ve gotta take a stand” against his parents’ utter disregard for him as an individual. This realization comes at the expense of Cameron’s shock when, on the way back from Chicago, Cameron notes the Ferrari’s odometer and freaks. Not everything about Ferris’ day off works according to plan.

Ferris’ idea of an escape becomes a journey into downtown Chicago. Hughes, whose teen years were spent growing up in Chicago’s suburbs, uses the second act portion of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off as a celebration of the city, a brief metropolitan love letter. With Sloane (a somewhat useless character) in tow, Ferris and Cameron visit various Chicago landmarks, including the Sears Tower, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, a Cubs game at Wrigley Field, the glorious Art Institute of Chicago, and the annual Von Steuben Day Parade. Though designed as a getaway, their day becomes a kind of spiritual awakening and vacation for Cameron (as Bill Murray’s character in What About Bob? said, “Take a vacation… from my problems!”). First, he’s swept up by Georges Seurat’s pointillist masterwork A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, where he identifies with the image of a little girl. As he looks at her, the shot gets closer and closer; the pointillism style is designed so that, as you look closer, shape and form disappear. Before long, Cameron sees nothing. Here, Cameron recognizes that he’s not living in his current state; the more you look at him, the less you see. Only later, when he inadvertently “kills” his father’s Ferrari, does he acknowledge that “I’ve gotta take a stand” against his parents’ utter disregard for him as an individual. This realization comes at the expense of Cameron’s shock when, on the way back from Chicago, Cameron notes the Ferrari’s odometer and freaks. Not everything about Ferris’ day off works according to plan.

That a teenager (Ruck was 29 while filming) needs to do something as melodramatic as “take a stand” against his parents speaks to Hughes’ thoughtful understanding of the teenage mindset, but it also reflects his treatment of adults in the picture. Every adult is, or is made to be, a clueless idiot—Ferris’ parents (Cindy Pickett and Lyman Ward were later married in real life, but then divorced ), droning high school teachers (Ben Stein’s career-starter as an economics teacher), the snooty (Snotty? Snotty.) maître d’ at the French restaurant, and even though he never appears onscreen, Cameron’s negligent father who rubs his classic Ferrari with a diaper. No one is more out of touch than Rooney, an iconic buffoon who’s so concerned about his image of authority that, as he sprints down the empty school halls, he slows abruptly in front of classroom doors. They’re all out of touch with teenage sensibilities and concerns, and Hughes’ teenagers are strangely aware of everything going on around them. Well, Ferris is anyway. The great epiphanies in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off belong to Cameron and Jeanie, the former who takes said stand, and the latter who stops resenting that her brother gets away with everything.

Hughes will be forever associated with creating believable teenage characters to whom audiences could identify, though his reach went far beyond creating three-dimensional adolescents. Hughes received his start writing popular 1983 scripts for Mr. Mom and National Lampoon’s Vacation. He moved to directing and defined the 1980s teenage experience with Sixteen Candles (1984), The Breakfast Club (1985), Weird Science (1985), and the script for Pretty in Pink (1986). Though he went on to far superior and far more commercially successful projects in the coming years, the Hughes brand name became one of transcending teenage groups (the jock, the nerd, the weirdo, the prom queen, etc.) into fully developed human beings. But his observations about middle-age experiences were just as astute in Planes, Trains and Automobiles (1987), She’s Having a Baby (1988), and scripts for Uncle Buck and Christmas Vacation (1988). His most successful script became Home Alone, 1989’s biggest hit. And whether or not he directed his scripts, you could always tell its author by Hughes’ specific brand of humor. Although his output faded in the mid-1990s until his death in 2012, Hughes’ legacy remains timeless.

Hughes will be forever associated with creating believable teenage characters to whom audiences could identify, though his reach went far beyond creating three-dimensional adolescents. Hughes received his start writing popular 1983 scripts for Mr. Mom and National Lampoon’s Vacation. He moved to directing and defined the 1980s teenage experience with Sixteen Candles (1984), The Breakfast Club (1985), Weird Science (1985), and the script for Pretty in Pink (1986). Though he went on to far superior and far more commercially successful projects in the coming years, the Hughes brand name became one of transcending teenage groups (the jock, the nerd, the weirdo, the prom queen, etc.) into fully developed human beings. But his observations about middle-age experiences were just as astute in Planes, Trains and Automobiles (1987), She’s Having a Baby (1988), and scripts for Uncle Buck and Christmas Vacation (1988). His most successful script became Home Alone, 1989’s biggest hit. And whether or not he directed his scripts, you could always tell its author by Hughes’ specific brand of humor. Although his output faded in the mid-1990s until his death in 2012, Hughes’ legacy remains timeless.

Revisiting Ferris Bueller’s Day Off today is less about traveling back in time to 1986 and more about remembering those feelings we all had during our high school experience. Although the film still makes us laugh with each viewing (no matter how many times we watch it), its resonance lies in Cameron’s storyline—and his crucial moment of self-discovery that one needs not have come from a dysfunctional family to understand. In fact, there would be no storyline, no purpose to the film at all without Cameron. Imagine Ferris Bueller’s Day Off without Cameron, and here is an eighties comedy with barely any conflict. After all, are we ever really worried that Rooney will catch Ferris? No, but the very idea of Cameron’s intense father relationship is frightening; it even scares Ferris a little. However appealing an escape to Chicago or any big city may be, Hughes’ story is far less frivolous and asks us to consider why those formative teenage years often stay with us. And like that decisive period in our lives, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off still hangs about and holds a special place in our hearts, but unlike our teen years might be, it’s a joy to revisit.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review