Father Mother Sister Brother

By Brian Eggert |

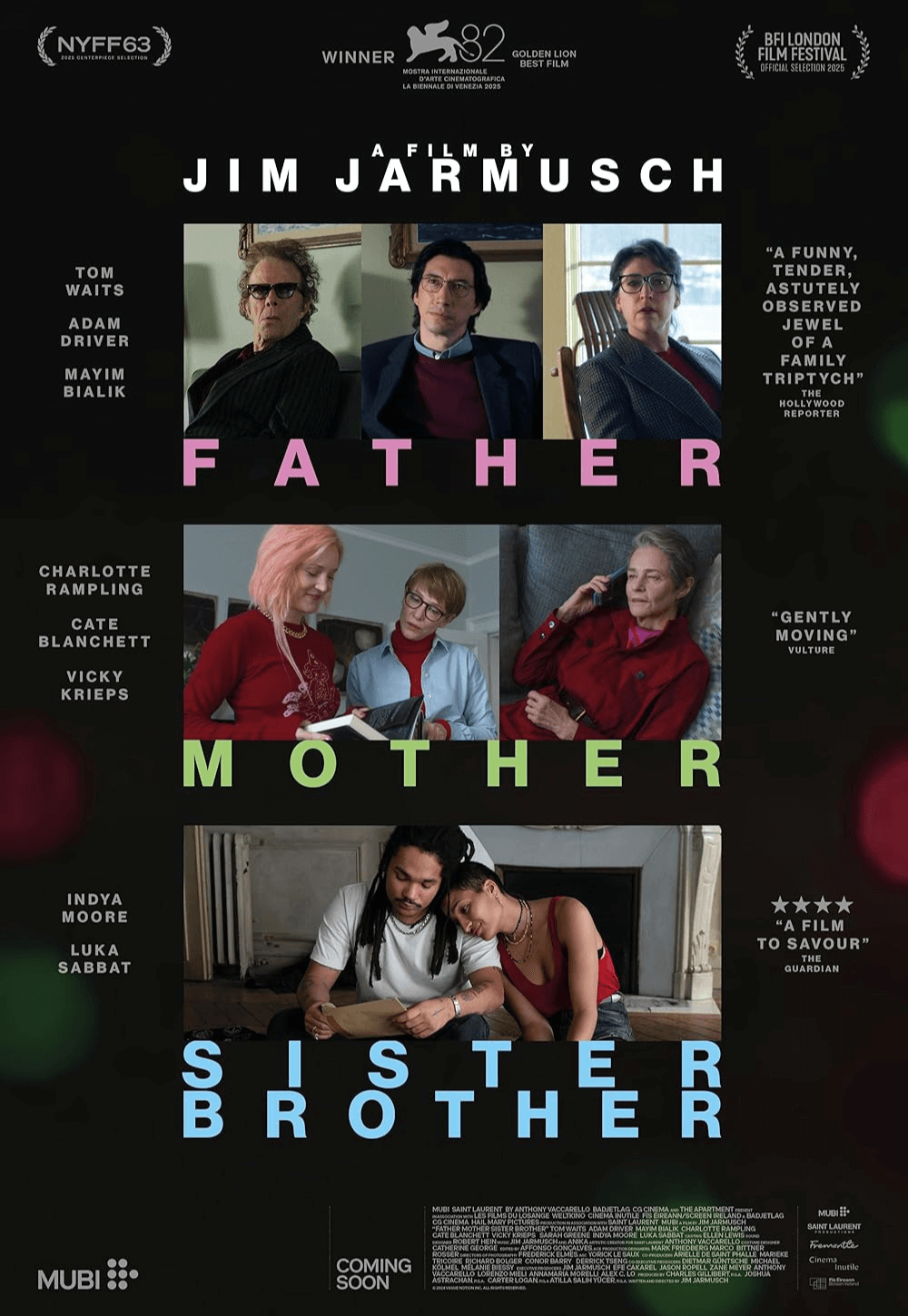

Jim Jarmusch establishes a few recurring motifs in Father Mother Sister Brother, his quietly overwhelming triptych of what one character, played by the incomparable Tom Waits, calls “family relations.” His anthology looks at three unrelated family gatherings, the first two between a parent and their two children, the last between twins who reconnect to settle their late parents’ affairs. In each story, the family members drive long distances to meet; some have newer vehicles, others drive jalopies. Wearing unintentionally color-coordinated attire, they engage in polite conversation and offer surface-level updates on their lives. They wonder whether one can toast with water, tea, or coffee; debate the purity of tap water; and question whether the Rolex being worn by a family member is real or a knockoff. In each chapter, someone says “And Bob’s your uncle” (or, alternatively, “And your uncle’s name is Robert”), skateboarders ride through each part in slow-mo, and quiet driving montages set the mood. And no matter how easygoing and uneventful these moments may seem, Jarmusch has an understated, effortless way of rendering the whole experience rather profound.

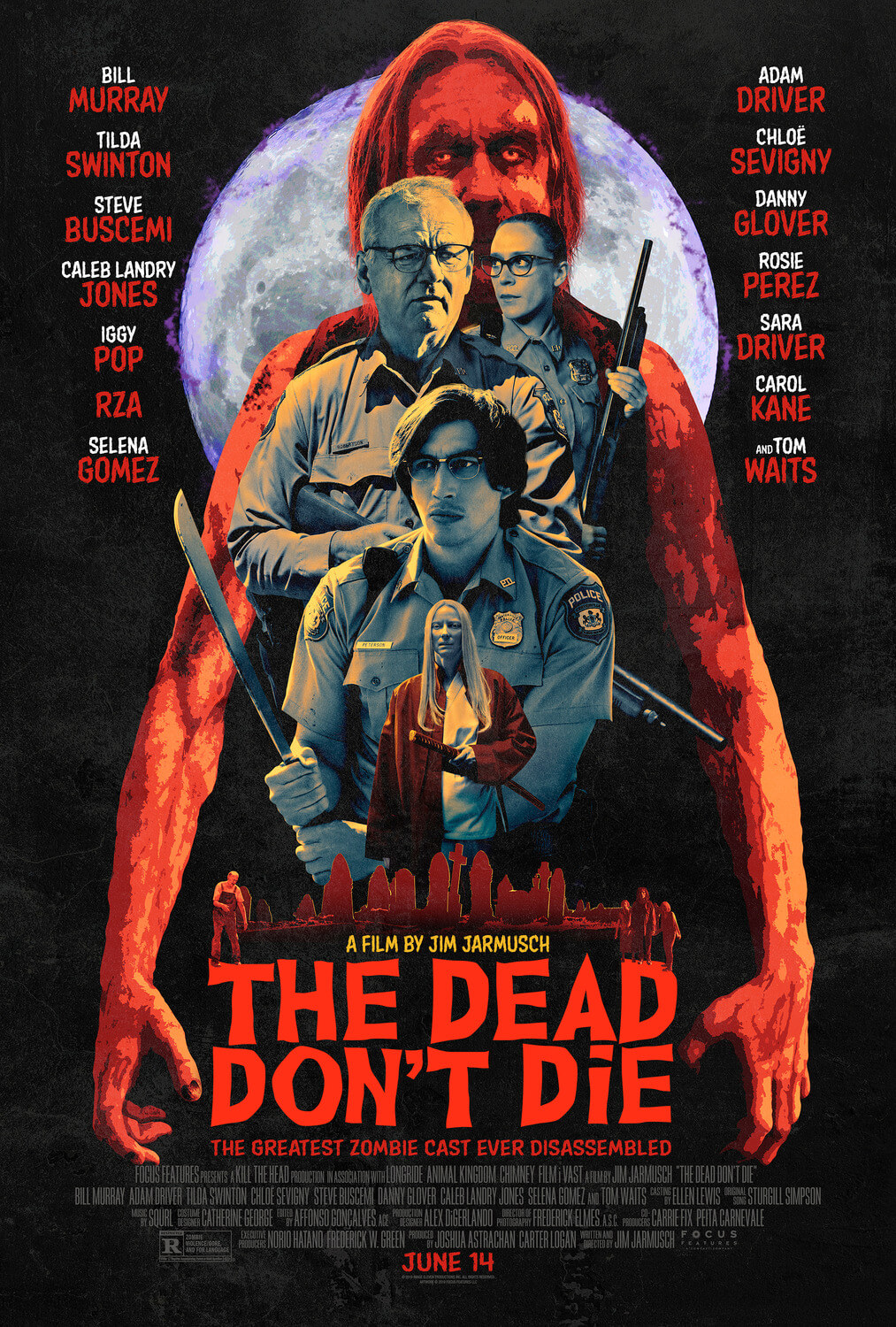

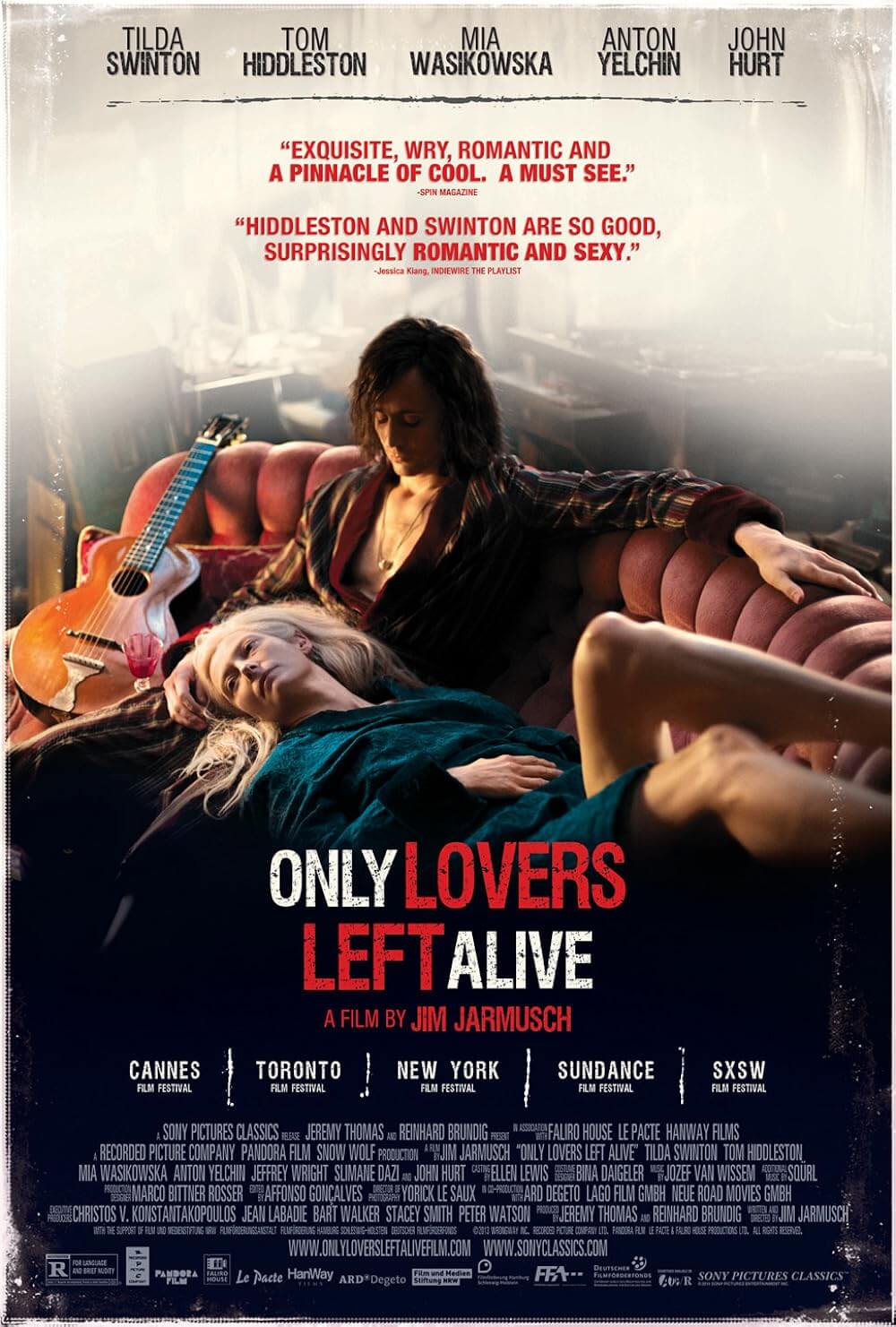

Jarmusch has maintained a consistent, idiosyncratic voice since his arrival on the American independent film scene in the 1980s. Though his work dabbles in various genres, he always regards his eccentric characters from an intriguing remove. The closest he’s ever come to “going Hollywood” is making a vampire movie with 2013’s Only Lovers Left Alive and a zombie flick with The Dead Don’t Die (2018). However, neither of those could be described as straightforward genre fare; they are defiant, darkly funny morsels that find Jarmusch mourning humanity’s apathy and decline, even while celebrating its cultural output. His films can feel at once remote yet intimate, quiet yet brimming with music, minimalist yet formidable in their impact. When he looks at the world, he does so through a singular artistic perspective that neither apes earlier filmmakers nor sets boundaries on his vision—especially in his many earlier film anthologies: Mystery Train (1989), Night on Earth (1991), and Coffee and Cigarettes (2003).

His latest opens with “Father,” about two siblings, Jeff (Adam Driver) and Emily (Mayim Bialik), driving to “nowheresville” in the Northeastern United States to visit their widower father (Waits) for the first time in two years. Jeff and Emily barely speak anymore, and when they talk about their dad, they worry about him living in the woods alone. He struggles to pay bills, and Emily barely suppresses her disdain for Jeff bringing him groceries or giving him money to repair a fallen wall, the well, and the septic tank. When they arrive at the carefully prepared house, situated “away from the so-called real world,” they find their father looking weathered and frail, and behaving somewhat strangely. Emily asks if he takes any medications. He says, “No. Do you think I should?” The visit avoids any serious conversation, feeling instead like a welfare check, or like they’re the parents who must monitor their older, irresponsible, perhaps unstable son. Once they confirm he’s stable, or stable enough, the children check their watches and begin to say goodbye before their stay is prolonged any further.

A similar situation unfolds in “Mother,” centered on Charlotte Rampling’s fussy, anal-retentive English author who lives in Dublin and has two very different daughters—the prudish Timothea (Cate Blanchett), nicknamed “Tim,” who lives in her mother’s shadow, and the younger sibling Lilith (Vicky Krieps), whose pink hair and rebellious attitude suggest she’s desperate to escape her mother’s looming influence. They all meet once a year for tea and polite conversation at their mother’s prim and proper table, where she dictates the fussy decorum, and everything’s in its right place. Once again, the conversation proves empty but revealing, with both daughters trying to impress their successful mother, who writes vaguely tawdry novels with titles such as Boundaries of Love and An Unfaithful Tomorrow. Lilith invents transparent stories about her success, and Rampling’s mother pretends to believe them; Tim has experienced genuine career growth, but her mother seems underwhelmed. Neither of them asks how their mother is doing, maybe because it’s evident from her stylish home and best-selling books that she prospers. Still, Jarmusch invites us to ponder the inner life of their mother, who first appears in a phone session with her therapist, hinting at a much richer interior world than the one she shows her progeny.

Jarmusch contrasts the stifling quiet of the first two chapters with “Sister Brother,” in which twins Skye (Indya Moore) and Billy (Luka Sabbat) meet for coffee and to look over their late parents’ Paris apartment. Both clad in black leather that reflects their determination not to be “squares,” their playful “twin factor” gives them an intimate shorthand with each other. But this is also expressed through their unreserved physicality. Whereas the goodbye hugs in earlier chapters look stiff and obligatory, the way Skye clings to Billy implies a lifetime of endearing closeness and openness that the previous families didn’t have. Even so, the same motifs of water, driving, and a Rolex appear in this moving final segment, along with questions about why their parents died in a mysterious plane crash. The end offers a warm, tender conclusion to a film that cuts into the ways family members communicate—or don’t—with each other. And throughout this entry and the others, Jarmusch never calls attention to the visual presentation, though cinematographers Yorick Le Saux, who shot the first two chapters, and Frederick Elmes, who lensed the third, give the picture an easygoing texture and carefully considered compositions.

Jarmusch explores the specificity of each family while acknowledging that the relations between some parents and their children have universal constants. When polite conversation runs out in each chapter, the characters sit in awkward if courteous silence. He observes that neither party shares everything with the other—how children often view their parents through a distorted lens and present a false version of themselves to gain approval, while parents sometimes keep secrets to maintain the parent-child dynamic or simply reserve a piece of their lives for privacy’s sake. For instance, Rampling’s chilly character refuses to discuss her written work with her children, and they regard her books with a curiosity so distanced that they don’t seem to have read them. Similarly, the siblings in the final chapter discover a collection of their parents’ forged documents and driver’s licenses, suggesting a life of intrigue, possibly even criminal in nature, before they had children. On that front, in a coda to the first chapter that might steal the whole movie, Jarmusch teases how Waits’ character may have the biggest secret of them all.

If Father Mother Sister Brother at first seems like a minor work by Jarmusch, it rewards closer inspection of the astounding work by the cast, using micro-gestures and subtle facial expressions to communicate who these people are without the need for exposition. Almost every moment feels at once underplayed yet entirely readable. Jarmusch also employs his quirky humor throughout, with winking motifs and recurring details. Although there’s hardly a deeper meaning to many of these devices, such as the Rolexes or the discussion of water, they’re connective tissue that—along with the impressionistic, shimmering transitions between sections—make the three chapters feel like parts of a whole. Some have questioned whether the film deserved the prestigious Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival last year, but Father Mother Sister Brother has a sneaky way of shedding light on family relationships and prompting introspection on how viewers interact with their own loved ones. It does so in a way that’s surprising, yet not surprising at all, given Jarmusch’s career of films that each seem closed off but eventually bloom into a cherishable, perceptive work of art.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review