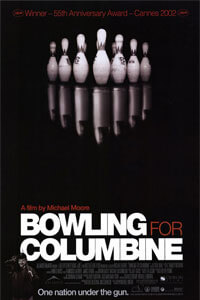

Bowling for Columbine

By Brian Eggert |

In the wake of recent mass shootings at schools, concerts, and other public events, it seems to be time to revisit Michael Moore’s Bowling for Columbine, his Oscar-winning documentary about America’s obsession with guns and violence. The steadily increasing rate of gun crimes and its place in our cultural consciousness today has risen to the point where the President of the United States, a maniacal former reality TV star with suspicious ties to Russia and porn stars, has suggested that schoolteachers carry firearms in the classroom—a suggestion that some people are actually taking seriously. How much the world has changed since Bowling for Columbine arrived in 2002, and how little effect it had, given the current state of things. To be sure, the issues and diagrams of gun violence used in the film almost seem commonplace today whereas, when the film was released, it seemed heartbreaking and tragic. A callus has formed in the interim, leaving us accustomed to constant gun-related headlines and political chaos that has become the new normal.

Moore’s film uses the 1999 school shooting in Littleton, Colorado as the impetus for larger discussion about the United States’ gun problem, and he proposes that fearmongering politicians, the NRA, media influencers, and capitalist interests have created a paranoid and lethally afraid culture compelled to arm itself for an unknown threat. His film entertains through humor, staged stunts, and his usual routine of ambushing his targets. To those who support firearms, such as NRA president Charlton Heston or a handful of gun-toting crackpots interviewed, Moore shows little respect or willingness to engage in intelligent discussion. Through it all, Moore asks questions: Why do Americans feel they need firearms? Why is America more violent than other countries? Looking for answers, he rounds up the usual suspects and scapegoats.

Is poverty to blame? Not likely, since Canada has a higher unemployment rate yet remains peaceful, so Moore claims. What about the effects of media violence and bad influences such as Marilyn Manson? Moore counters that Japan consumes violent video games and movies far more than most cultures, yet they don’t have an issue with gun violence. Manson himself explains in an thoughtful interview, “I think it’s easy to throw my face on the TV because, in the end, I’m a poster boy for fear. Because I represent what everyone is afraid of. Because I say and do whatever I want.” And what of the bloody history of the United States? In a conflicted sequence (set to Louis Armstrong’s “What a Wonderful World”), Moore presents a montage of the United States’ horrific crimes, many of them too easily forgotten: the U.S. overthrowing various world leaders in Iran and Guatemala, backing ruthless leaders in Chile and El Salvador, the Vietnam War, the Iran-Contra affair, Manuel Noriega, bombings in Iraq and Sudan, and the CIA training of Osama Bin Laden who later carried out 9/11. Even so, Moore follows this sequence by noting that the imperialist British Empire and Nazi Germany did much worse.

As a young film enthusiast, Moore’s documentaries made an impact on me. His debut, Roger & Me (1989), was the first documentary I had ever seen at a very young age and, seeing something entertaining that spoke to me, I followed Moore’s career, watching his films and television shows (TV Nation and The Awful Truth), enjoying his methods to varying degrees while usually agreeing with the overall message. His material provided an entry point into the so-called nonfiction medium long before his copycats produced an insurgence of disposable docs that have arrived in surplus on Netflix. Moore represented—and still represents—one of the only documentarians capable of delivering blockbuster numbers at the multiplex. But as audiences have become wise to the illusory objectivity of the documentary format, the appeal of Michael Moore has cooled over the years. Revisiting Bowling for Columbine more than fifteen years after its release, I found myself annoyed and skeptical by his gimmickry. Although it’s difficult not to agree with Moore’s thesis, his disorganized methods prove rambling and seldom on-point.

As a young film enthusiast, Moore’s documentaries made an impact on me. His debut, Roger & Me (1989), was the first documentary I had ever seen at a very young age and, seeing something entertaining that spoke to me, I followed Moore’s career, watching his films and television shows (TV Nation and The Awful Truth), enjoying his methods to varying degrees while usually agreeing with the overall message. His material provided an entry point into the so-called nonfiction medium long before his copycats produced an insurgence of disposable docs that have arrived in surplus on Netflix. Moore represented—and still represents—one of the only documentarians capable of delivering blockbuster numbers at the multiplex. But as audiences have become wise to the illusory objectivity of the documentary format, the appeal of Michael Moore has cooled over the years. Revisiting Bowling for Columbine more than fifteen years after its release, I found myself annoyed and skeptical by his gimmickry. Although it’s difficult not to agree with Moore’s thesis, his disorganized methods prove rambling and seldom on-point.

Of course, Moore places himself at the center of his film. He offers a first-person documentary experience filled with ironic, subversive humor designed to create social unrest and outrage. People should be outraged on this topic. But Moore’s glib attitude and jokes occasionally diffuse the seriousness of his discussion. The film amounts to infotainment, heavy on the ‘tainment. An entire scene might be a comic bit that does nothing to reinforce the arguments of his documentary. Take a scene where a man explains why he has a gated front door. Moore interrupts him and asks if he could get a spear through the gate. The purpose of the scene is not to explore truth or reveal facts, but instead to allow room for Moore’s shtick. He points out the ineffectiveness of a gated door against spears—a nonsensical suggestion to be sure—whereas he already took the joke to its destination by looking around the peaceful neighborhood and asking, “Where are the rapists and killers?”

Many of Moore’s critics have raised questions about his creditability and methods. Moore represents himself as an American servant from the heartland of Flint, Michigan, as his drab clothing, baseball cap, scruffy facial hair, and everyman appeal suggest. Nevermind that he’s now a millionaire; his rotund body and cheap wardrobe create an effective juxtaposition. When he ambushes one of his well-dressed executive targets and carries an air of obliviousness about official channels or how to schedule a simple appointment with a high-level official, he makes himself into David fighting Goliath. He’s also been accused of doctoring footage and distorting facts to propel his argument through selective editing. But documentarians have been misrepresenting reality in favor of their vision since Robert J. Flaherty first met the Inuit hunter Nanook. Viewers expecting objectivity from any documentary must learn that objectivity is a myth.

Arguments condemning Moore’s approach are nothing new. Detractors have faulted him for his outspokenness and characterize him as representative of the leftist ideology, using the man to condemn the viewpoint. Labeling Moore’s complaints about the state of America as mere leftist cynicism seems reductive and naïve, and also misses the underlying injustice called out in many of Moore’s films. Other Moore critics note how unproductive his stunts can be. Watch Moore ask low-level Kmart employees for a refund on bullets still lodged in the teen victims of the Columbine massacre. What does this accomplish, besides a good show? This is not to suggest that Moore must be humorless to make a point; however, his antics sometimes lead nowhere except a joke or an entertaining scene. Such moments would be more effective if they could reinforce his point while also being funny. Nevertheless, these elaborate and often chuckle-worthy stunts gain attention and remain controversial for making a scene, and starting a conversation amid viewers.

It’s sheer dumb luck that one of Moore’s otherwise pointless stunts pays off in Bowling for Columbine. When he attempts to return those Columbine bullets to a Kmart executive, he set out to accomplish nothing more than embarrassment for employees of the retail outlet. It’s entertaining to watch, to be sure, but where does it lead? If his goal in this stunt is to get Kmart to stop selling bullets, Moore doesn’t directly ask this of the exec. Instead, he arranges this awkward situation that, in the moment, humiliates the retail bureaucracy. Kmart decides to stop selling bullets on their own (a choice undoubtedly made based on Moore’s attention to the issue and fear of media reprisals). The correlation between Moore’s stunt and the outcome seems unintended, which he openly admits in the film. The purpose, then, was far less constructive.

It’s sheer dumb luck that one of Moore’s otherwise pointless stunts pays off in Bowling for Columbine. When he attempts to return those Columbine bullets to a Kmart executive, he set out to accomplish nothing more than embarrassment for employees of the retail outlet. It’s entertaining to watch, to be sure, but where does it lead? If his goal in this stunt is to get Kmart to stop selling bullets, Moore doesn’t directly ask this of the exec. Instead, he arranges this awkward situation that, in the moment, humiliates the retail bureaucracy. Kmart decides to stop selling bullets on their own (a choice undoubtedly made based on Moore’s attention to the issue and fear of media reprisals). The correlation between Moore’s stunt and the outcome seems unintended, which he openly admits in the film. The purpose, then, was far less constructive.

Bowling for Columbine remains one of Moore’s most entertaining films; in other words, the film contains numerous stunts and attempts at drama. He transitions into discussions of South Park, bees, pollution, COPS, and Dick Clark—each topic providing a detour from the arguments at hand, each providing him with another opportunity to entertain rather than inform. Moore’s flippant strategies are contrasted by touches of seriousness, which at times feel like an affectation. His confrontation of Heston, for instance, begins with Moore revealing his own NRA card. But the discussion quickly descends into an impossibly one-sided argument. Moore confronts Heston for his insensitivity, as the actor-turned-spokesperson held NRA meetings in cities just days after local shootings, and Heston called his behavior “courage” in defense of NRA values. Nevertheless, had Heston anything reasonable or cohesive to say in his defense (he doesn’t), one gets the sense that Moore wouldn’t have shown that footage anyway.

The very title—Moore’s sardonic assertion that shooters Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold bowled the morning of the shooting, and therefore bowling must be the reason they carried out this act—is a silly and nonsensical joke. The frustrating part is, despite Moore’s penchant for distasteful showboating, I usually agree with his politics and his complaints about the state of America. The general outcome of Bowling for Columbine brings into question why the United States remains so fixated on guns. Though his approach is disorganized and rooted in a disconnect between his humor and his objectives as a filmmaker, his film starts an important conversation. More successful, focused applications of his humor and politics can be found in Sicko (2007) and Where to Invade Next (2015), titles less dependent on ridiculous stunts and with decidedly fewer pointless confrontations. In the end, Moore’s heart remains in the right place. And upon revisiting Bowling for Columbine, the film’s continued relevance is impossible to ignore. But the conversation that takes place after viewing his film is bound to be more incisive and discerning than anything addressed onscreen. Perhaps that’s enough.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review