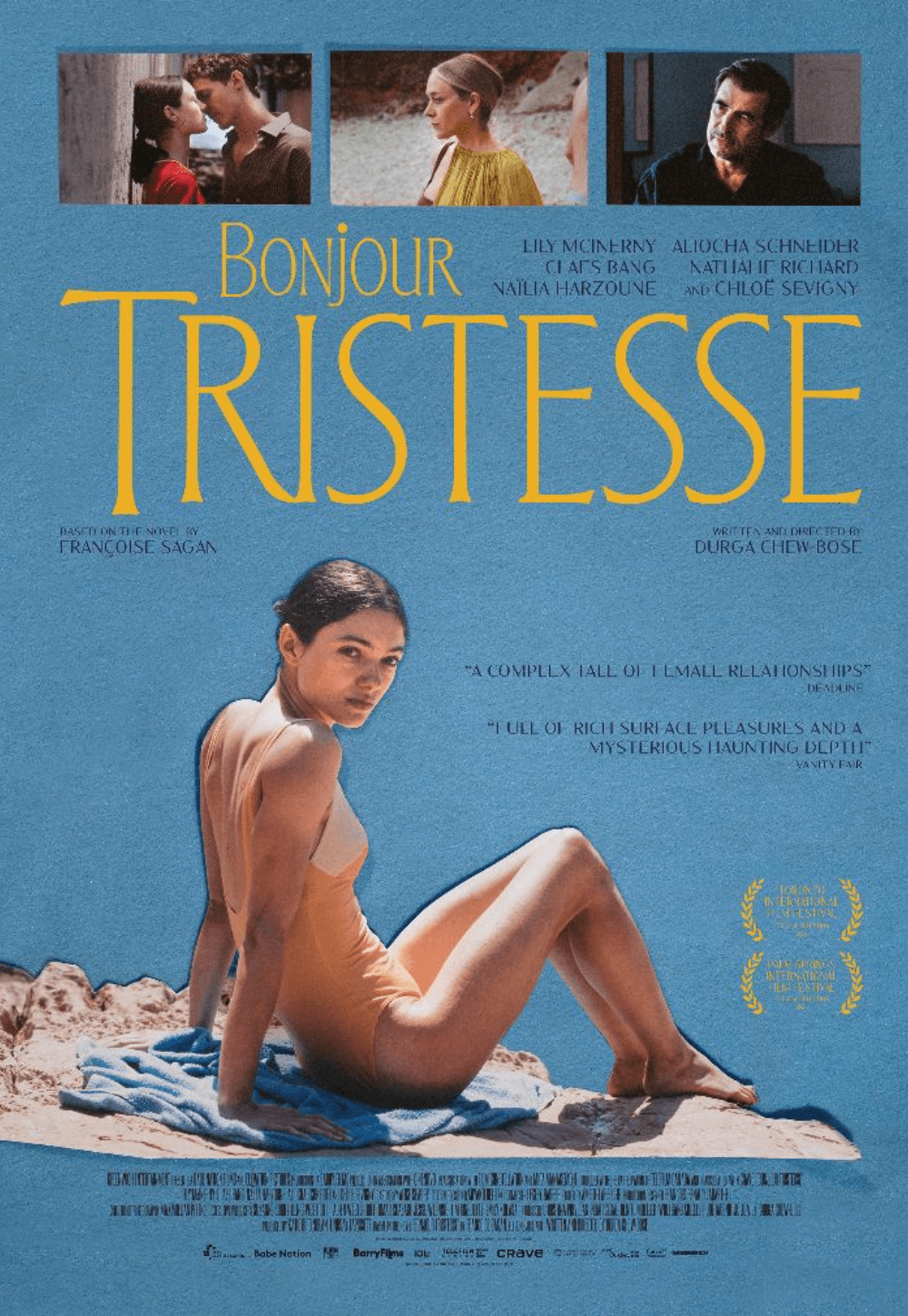

Bonjour Tristesse

By Brian Eggert |

A new adaptation of Bonjour Tristesse, a novel written by Françoise Sagan in 1954 when she was just 18, feels at once necessary and untimely. Otto Preminger directed the Hollywood version released in 1958, and the notorious taskmaster reportedly treated star Jean Seberg, whom he discovered and cast in Saint Joan the year before, with cruel ferocity, commanding her every movement and expression until she felt like an automaton. As for the film, Preminger wasn’t so interested in exploring the inner life of his central female character but rather in translating Arthur Laurents’ script to the screen, leaving the book ripe for reconsideration. Sure, Preminger’s film broached some taboo subject matter for the time, giving his stars, including Deborah Kerr and David Niven, involved scenes to play. The material’s portrait of its teenage protagonist’s moral ambivalence, sexual exploration, and ultimate loss of innocence was regarded as groundbreaking for its treatment of an adolescent—then a group given little emotional integrity in cinema. But today, in the wake of countless teen movies and shows, something like Bonjour Tristesse risks feeling like white noise.

This is not to discredit the work by first-time writer-director Durga Chew-Bose. Her Bonjour Tristesse is an entrancing experience much more rooted in a complicated young woman’s mind than Preminger’s film. The new version feels like a natural extension of the Montreal-born creative’s series of essays called Too Much and Not the Mood, published in 2017, which explores the identity soup of her relationship with film and other art, her recollections of childhood, and her inner life. How appropriate, then, that she should be drawn to Sagan’s novel and its curiosity about the emotional landscape of Cécile, a 17-year-old girl on the cusp of womanhood. Far less concerned about the plot mechanics than Preminger’s film—concerning Cécile’s meddling in her father’s love life—Chew-Bose’s Bonjour Tristesse is an impressionistic portrait of its central character’s internal world over a formative summer, where she learns agency, and not always in healthy ways. Whereas Preminger explored Cécile’s mind with clunky voiceover and overstated emotions, Chew-Bose understands that the camera can observe thought and respects her audience’s capacity to read her actors’ faces.

Lily McInerny plays Cécile with a detached presence, though it’s part affectation, part genuine. Spending a summer on the French Riviera with her widower father, Raymond (Claes Bang), and his French girlfriend, Elsa (Naïlia Harzoune), Cécile’s life is uninhibited by the adults around her. She smokes, drinks champagne, and carries on with her boyfriend, Cyril (Aliocha Schneider), in the presence of her father. They have an intimate father-daughter relationship, where they play solitaire together and call each other by their first names. Elsa asks why they don’t play a more competitive card game. “Sorta feels like we are,” Raymond replies. This dynamic soon changes with the arrival of Anne (Chloë Sevigny), a cosmopolitan fashion designer and longtime friend of Raymond and his late wife. Unlike Elsa, Anne is hard to know and not easy to smile. She also has immediate concerns about Cécile, whose future schooling remains in question. Anne wants her to study (“How will she know what she’s passionate about?”) and for Raymond to set some boundaries (“She’s not going to stay close just because you give her so much room”).

If one were to summarize the plot of Bonjour Tristesse, one might explain that when Raymond leaves Elsa for Anne, Cécile conspires with Cyril and Elsa to manufacture enough tension to cause them to split. It’s a cruel scheme occupying much of the screen story in Preminger’s version. Chew-Bose recognizes that there’s more to this than some gimmicky anti-matchmaker scenario. Her film is entrenched in Cécile’s growing complexity and lingering teenage petulance, making this coming-of-age story about a character who’s far from virtuous or single-minded but well on her way to becoming a multidimensional person. She tries to sneak away with Cyril and hops into his bed at one point. “You’re reckless and careful,” he tells her. Elsa sees this, noting how Cécile is practicing how to be seen, not looked at, something Raymond has trouble understanding. Her behavior ranges from destructive to affectionate, especially with Anne, who goes from a cherished role model to a figure of authority Cécile rebels against.

Rather than focusing on the story alone, Chew-Bose captures a mood. Maximilian Pittner’s camera never luxuriates in the stunning scenery or the cast in the way Paolo Sorrentino did in the recent Parthenope. Instead, the director and her editor, Amélie Labrèche, deploy an evocative presentation of time, where summer days pass as if in a dream. If Preminger’s film feels direct and structured, Chew-Bose’s unfolds less like a recollection with a narrative certainty about what happened on which day, but rather, a series of impressions from the summer. It brought to mind the transfixing atmosphere of Call Me by Your Name (2017). However, Chew-Bose resolves to update the story to the present. But even with the presence of smartphones, some of the costumes feel vintage. It was perhaps a misguided choice to update the material, but it mostly works. Moreover, almost as if winking at her film’s translation from a French novel written in the 1950s, previously adapted by a formative Hollywood director, her version’s soundtrack features modern covers of mid-twentieth century hits, such as “Blue Skies” and “Come Softly to Me”—like the story, at once an evocation of the past and contemporary.

Other critics have argued that Sevigny, once an upstart in the independent film scene, is miscast as a figure of elegance, while praising how the attractive Bang and newcomer Harzoune fit better into their roles. I couldn’t disagree more with the first part, as Anne is never quite as resolved or poised as she may seem (despite her impressive pineapple-slicing skills). Anne feigns certainty and shares her self-doubt with Cécile, who’s at a point in her life when she absorbs everything. Although Anne says, “I’m uncomfortable around adults who don’t know themselves,” it’s worth questioning to what extent she knows herself or feels whole. Chew-Bose confronts how identity is an ever-moving target, always morphing, always leaving us searching. Best of all, she approaches her film thoughtfully, adding an original coda set sometime later in the narrative. It’s a glimpse at what Cécile—who now wears her hair like Anne’s, blonde, in a portal-like bun, and embraces Anne’s penchant for red clothing—has learned from these events. Is she merely replicating how Anne alternates between coldness and warmth, or did her experience with Anne bring out something that was always there in her? The answer is as enigmatic and indeterminate as the human psyche.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review