Aloha

By Brian Eggert |

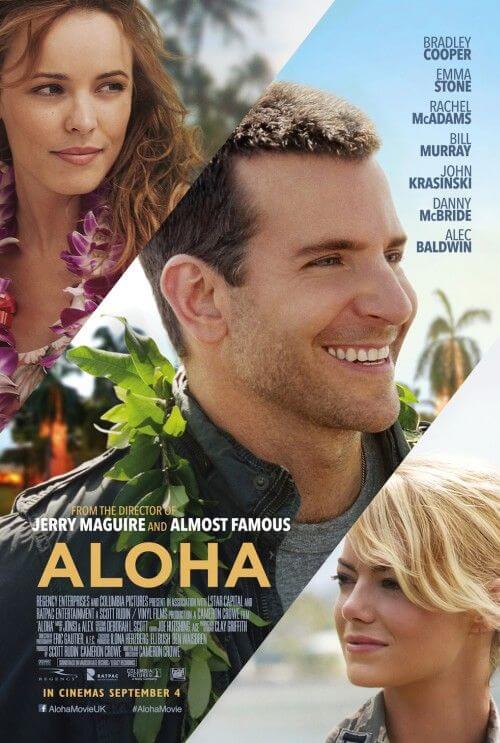

Cameron Crowe’s writerly self-indulgence turns his latest opus, Aloha, into an incoherent jumble of unrealized subplots, desperately whimsical behavior, overcomplicated backstories, and forced romantic chemistry. At the very least, Crowe’s deep appreciation for his film’s Hawaiian backdrop remains unmistakable, even if everything else about this romantic comedy is a confusing mess. Crowe weaves together a half-dozen subplots, tossing in the kitchen sink and all, in a manner that feels like an artist with too many ideas trying to get them all out at once. No doubt Crowe’s editor Joe Hutshing had a pickle of a time trying to assemble the footage into a cohesive film—a task at which he ultimately failed. Indeed, Aloha feels like a patchwork, assembled out of unfinished moments between underdeveloped characters. Perhaps on his reputation alone, the writer-director assembled his impressive all-star cast—including Bradley Cooper, Emma Stone, and Rachel McAdams—to perform in this untidy story of redemption, but even the pretty faces that carry the picture can’t make up for the overwritten screenplay.

Cooper is Brian Gilcrest, a former pilot and space enthusiast with a shadowy past in the Middle East. Now he’s a defense contractor hired by an eccentric billionaire (Bill Murray) to oversee the blessing of a local Hawaiian gate, whose significance is obscure at best. Accomplishing this task requires Gilcrest to return home to Hawaii for tense negotiations with natives over the relocation of ancient remains, a satellite launch, and a love triangle. He’s assigned a bright attaché, go-getter Air Force pilot Allison Ng (Stone), who’s the obvious love interest (and supposedly a quarter Hawaiian, despite Stone’s blonde hair and blue eyes). But returning to Hawaii has also brought Gilcrest back to Tracy (McAdams), his ex-girlfriend from 13 years ago. She’s since been married to never-present military man Woody (John Krasinski) and has two children, a 12-year-old girl (Danielle Rose Russell) and a rambunctious younger boy (Jaeden Lieberher) with a penchant for recording everything on video. Both children are plot devices.

Though casting Stone may not scream cultural sensitivity, Aloha does make an effort to dabble in Hawaiian mythology and tradition. Nation of Hawaii leader Dennis “Bumpy” Kanahele, a descendant of Hawaii’s King Kamehameha, plays himself (wearing a T-shirt that reads “Hawaiian by Birth, American by Force”) in several scenes, offering a chance to get his sympathetic message to a wider audience. And as Gilcrest and Ng fall for each other, they debate their belief in mana, meaning power and spirituality—a notion reinforced by Tracy’s boy, who seems to think Gilcrest is Lono, a deity who will be whisked away by the goddess Laka for marriage and “revenge sex”. Crowe incorporates whispering voices and mysterious gusts of wind that seem to reinforce the idea that the Hawaiian myths are real, including one scene where apparitions walk across the street. Ng believes in them wholeheartedly, while Gilcrest remains ever the skeptic. The myth strain of the plot eventually fades away, conceding to the U.S. military and a space launch.

With Gilcrest’s return, the ever-confused Tracy indulges a rocky period in her marriage to Woody, whose running gag involves silent, rugged-man pantomimes of his feelings, occasionally set to subtitles. As their marriage begins to stumble, the possibility of Tracy and Gilcrest getting back together threatens the blossoming Gilcrest-Ng romance, while Tracy also delivers predictable news about her daughter’s real biological father. Meanwhile, Gilcrest’s former military liaisons, General Dixon (Alec Baldwin, in Glengarry Glen Ross mode) and Colonel “Fingers” (Danny McBride), put pressure on Gilcrest to carry out his mission, regardless of a new development that suggests Murray’s character may be trying to launch weapons into space out of sheer paranoia. With Crowe’s screenplay pulling Gilcrest in so many varying directions, it’s difficult to know where Aloha’s center resides, in part because each of these subplots leaves much room for further exploration. And then there are random, goofy asides, such as Gilcrest having another man’s big toe sewn onto his own during wartime, which has left his foot looking freakish for no reason whatsoever.

Worse, Crowe’s dialogue consists of speedy exposition and shorthand, and often cryptic emotional declarations; the viewer feels like they’re spying on several longstanding relationships, wherein the characters don’t need to say everything because they inherently know the other person. Unfortunately, Crowe doesn’t allow the audience to join their inner circle, not completely, and we feel like outsiders for the duration. The effect of Aloha is strange, giving you the sensation that you’ve missed something, some cue that would indicate why this or that character behaves this way. In fact, you haven’t missed a beat; these are just bizarrely written characters trapped in disorderly storytelling. The haphazard way in which everything works out, complete with a puzzling and expository account of what actually happened long after the fact, brings a rushed closure to the proceedings. Fortunately, many of the actors remain so charming that watching them, even in a film as slapdash as this, makes the entire experience better than it really is. But that doesn’t mean Aloha should be considered passable.

Crowe’s appreciation of Hawaiian culture is respectable and palpable in the scenes in Kanahele’s mountain village, where his people gather for music and food, and an unmistakable togetherness consumes the moment. Elsewhere, during a typical rom-com montage of Gilcrest and Ng trying on hats and playing with coins in a marketplace, Crowe’s delivery feels hackneyed and generic—made worse from the handheld camerawork by Eric Gautier, whose proclivity for close-ups seems determined to fill the entire theater screen with one big head at a time. Of course, Aloha’s soundtrack and pop-culture references are top-notch, because the film’s director has impeccable taste in that regard, but the film is a far cry from Crowe’s iconic work on Say Anything (1989), Jerry Maguire (1996), and Almost Famous (2000). Even his remake Vanilla Sky (2001) feels more straightforward. To be sure, Aloha is probably Crowe’s worst film, worse even than Elizabethtown (2005), and that’s saying something.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review