Magellan

By Brian Eggert |

An indigenous woman in Malacca forages in a stream until she sees something that terrifies her. She runs through the forest back to her people and shouts, “I saw a white man!” Her tribe gathers to perform a ritual, chanting, “The promise of the gods of our ancestors is upon us.” They sacrifice an animal and cover her in blood. But their ceremony won’t help. The year is 1511, and the Malaysian state will be conquered by Portuguese explorers who would sooner wipe out the locals than allow them to live without Christianity. In Lav Diaz’s arthouse epic Magellan (Magalhães), the Filipino director resists the usual trappings of a historical biography by avoiding any hint of romanticism. Diaz provides an alternative to the sweeping period-drama aesthetic of similar films—see Ridley Scott’s methods across everything from 1492: Conquest of Paradise (1992) to his Gladiator movies—with his slow-cinema technique of long shots, minimal dialogue, and immersive patience. It’s a formally inspired piece of work that evokes more admiration than passion, but its vision is commendably uncompromising.

Admittedly, this is my first Diaz film. Although he’s been directing since the late 1990s, few of his features have been distributed in the United States outside of the festival circuit. That’s in part because he maintains a reputation for making films with runtimes ranging anywhere from four to ten hours. Magellan is a brisk 160 minutes by comparison, marking not only one of his shortest features but one that’s bound for proportionally wide distribution thanks to Janus Films. Here, Diaz frames his story within the boxy Academy Ratio that many arthouse filmmakers have employed in recent years to capture a perspective in symbolic terms, either personal or societal, narrowed by external or existential forces. In this case, the perspective is that of imperialists who believe the only humanity worth a damn is Christianity, and that everyone else should be punished for not adopting their worldview. And after the native Malaccans see the Portuguese in the first scene, Diaz returns to them later in the aftermath, slaughtered by colonists intent on bringing God’s unfailing love.

Ferdinand Magellan is played by Gael García Bernal, the Mexican actor whose marquee name no doubt attracted more interest from international investors and distributors than Diaz usually sees. Bernal is excellent in the part, playing a protagonist whose initial role under conquistador Afonso de Albuquerque (Roger Alan Koza) quickly establishes him as no hero. Of course, at the time, he was a faithful servant of King Manuel, carrying out the era’s seemingly noble mission of spreading Christianity, ensuring the downfall of Islam, and welcoming the arrival of Judgment Day. Today, this era of Portuguese history registers as a grim period of colonialism and genocide. Diaz presents the story with recognition that the real mission is more superficial. “We work for his greed,” says Magellan, referring to his king. To be sure, the soldiers acknowledge that colonialism will make their leaders rich and leave them poor. “They need us more than we need them.”

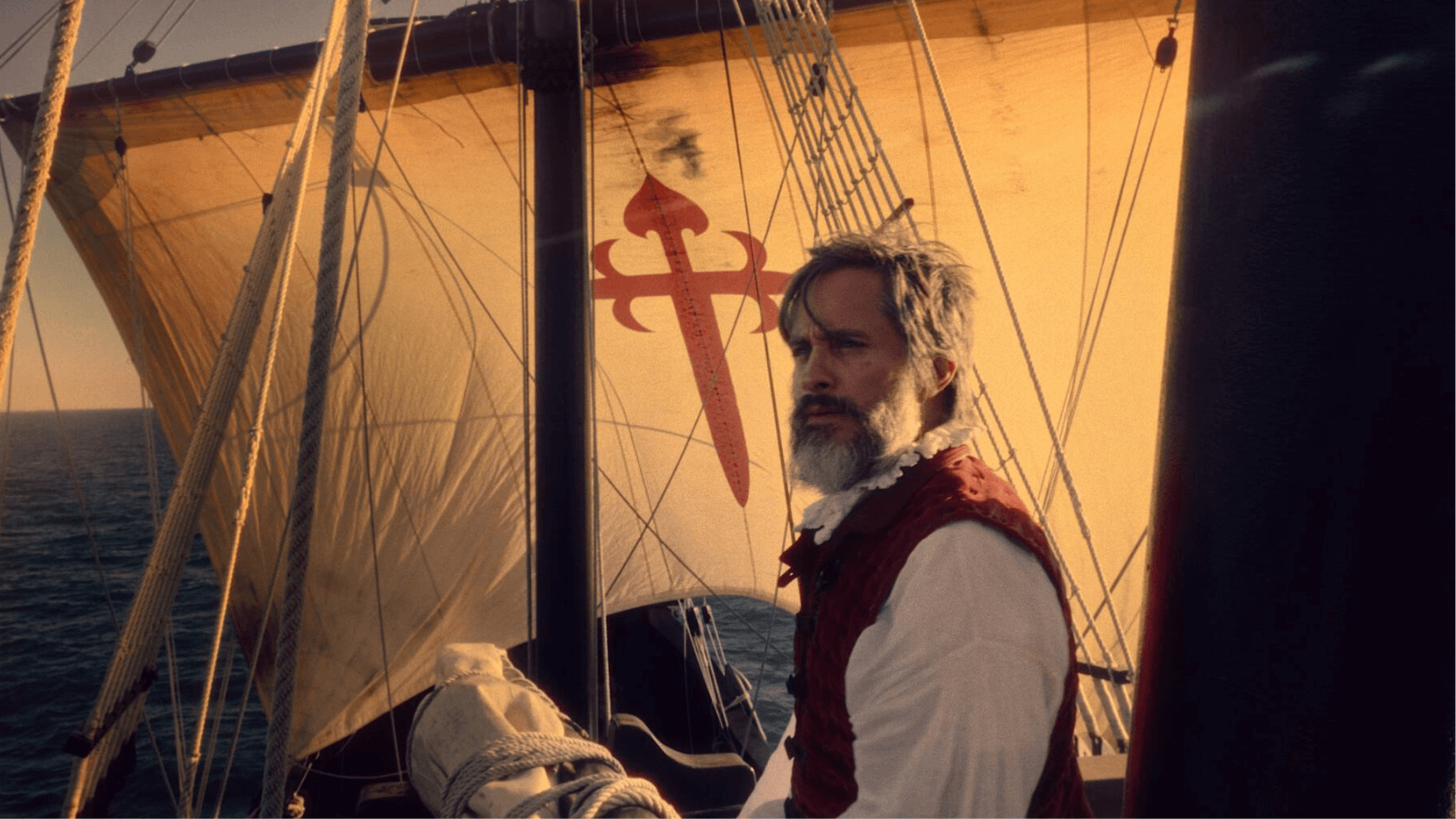

Even so, once he’s promoted, Magellan heads an expedition that finds his ship navigating the Atlantic and Pacific to find better trade routes and chart a path around the planet. Much of the film’s middle section takes place at sea, where boredom and despair, compounded by Magellan’s ambition and dogmatism, lead to a power struggle and the brutal punishment of dissenters. The desperate undertaking, which reveals his cruelty as a leader, requires him to beg for forgiveness and to ask God for help to save lives, despite his inherently destructive mission. When his crew arrives in the Philippines a decade later, there’s a maddeningly ironic sequence where he tries to explain to the locals that their fear of a Wak-Wak, a malignant phantom, is irrational because no one has ever set eyes on it—but he ignores how his Christian myths might sound to them. The locals who refuse to comply are declared heretics, their huts burned down, and their people slaughtered. Eventually, their rebellion in the Battle of Mactan marks Magellan’s demise.

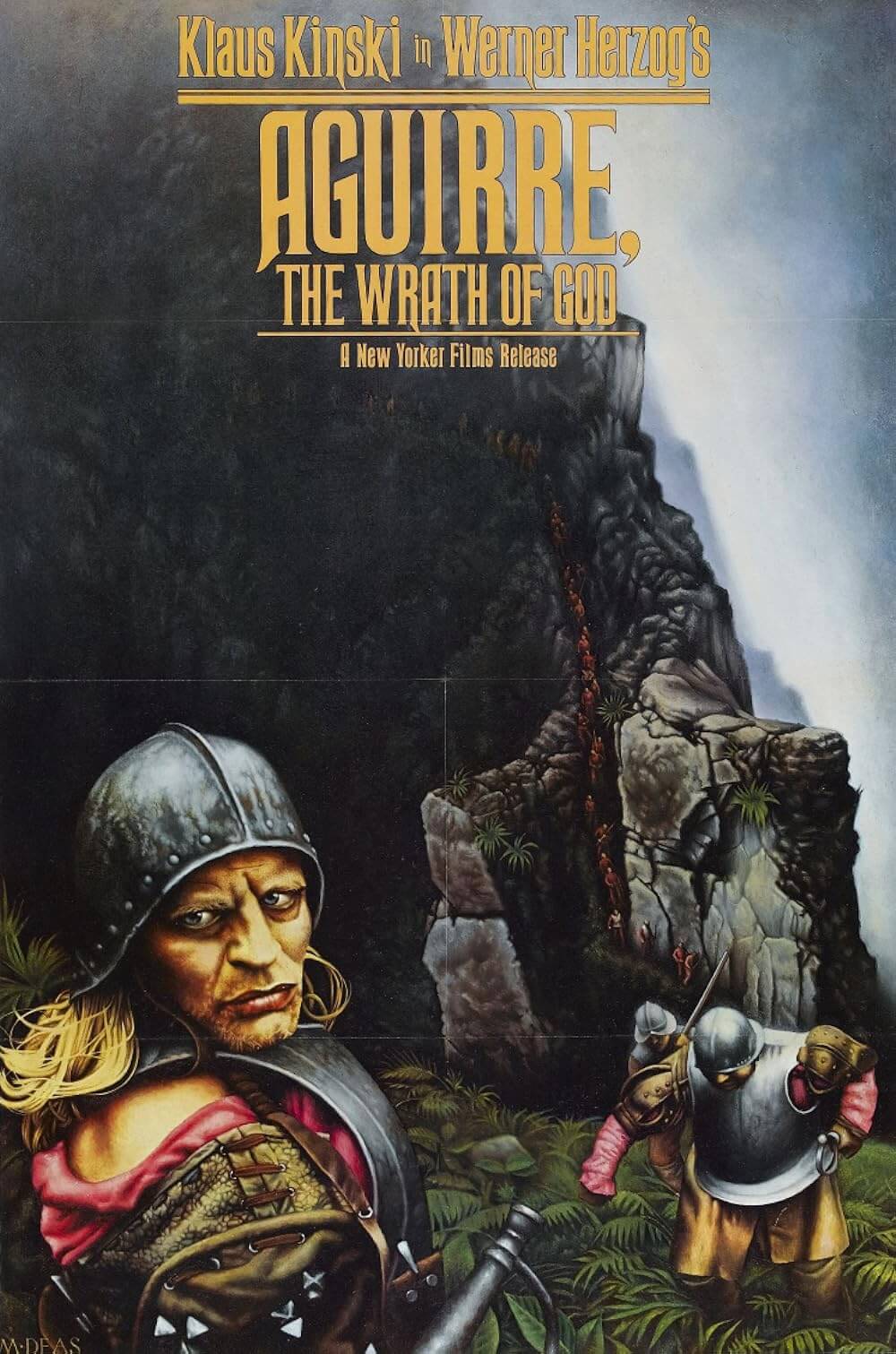

Watching Magellan is less about following a narrative path than about immersing oneself in Diaz’s beautiful and transfixing production. The filmmaker’s approach cannot help but evoke Werner Herzog’s hopeless, entrenched aesthetic in Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), particularly in early sequences. Magellan and his crew navigate dense forests and explore rivers in long, immersive shots that capture the sweltering atmosphere and impossible terrain—much of it littered with dead villagers. Magellan isn’t quite the madman that Spanish conquistador Lope de Aguirre was, but he’s hardly the laudable historical icon renowned for global circumnavigation. Like most prominent figures from the Age of Discovery (Christopher Columbus, Hernán Cortés, et al.), his history is marred by today’s post-colonial worldview that recognizes the agenda of wealth and indoctrination that drove explorers. And his vows to wipe out other cultures and instill his own have a chillingly familiar ring, similar to today’s right-wing, crypto-fascist ideology that has revived imperialist attitudes.

Most compelling is a subplot involving Enrique (Amado Arjay Babon), a Malaccan native whom Magellan captures and makes his trusty companion. Enrique remains by Magellan’s side for much of the film until the final stretch in the Philippines. When Magellan’s authority wanes and his imperialist power seems at an end, Enrique escapes his veritable imprisonment and rebels. The narrative follows Frantz Fanon’s trajectory of colonialist power, where the imperialist’s grip on the colonized becomes so tight that the indigenous people resist and become stronger in their fight for independence. Diaz’s film presents a sober take on its subject, but Magellan, as a viewing experience, feels more about the production’s formal austerity than its historical implications. As I watched the film, I found my attention wavering between the story and the impressive production design (by Isabel Garcia and Allen Alzola)—including actual sailing ships and a stunning array of shots that Diaz and his co-editor Artur Tort hold for longer than another filmmaker might. This is refreshingly patient storytelling that transfixes with its unyielding approach, leaving an imprint on the viewer that lasts well after the end credits roll.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review